This picture was shot by portrait photographer MikhaIl Panov. He was famous for his incredible lighting skills. In this photo, he captured professors of the Moscow Conservatory. The photo dates back to around the end of the 1860s — early 1870s.

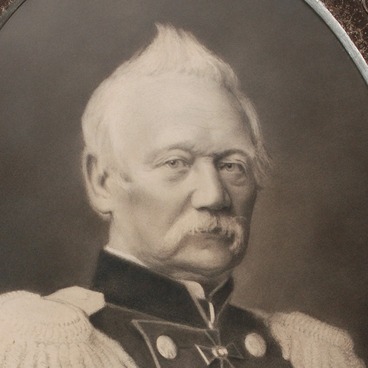

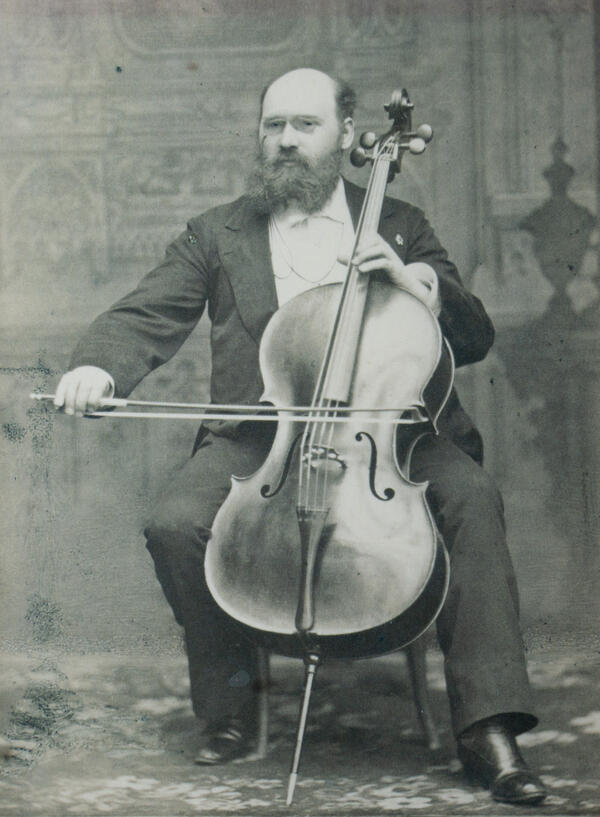

A photo of the Conservatory’s founder Nikolai Rubinstein is in the very center, at the top of the picture. He remained the institution’s director until his death in 1881. A photograph of Pyotr Tchaikovsky occupies an honorable spot, to the right of the director.

Tchaikovsky came to Moscow in January 1866 when he was offered to teach the theory of music at Musical Classes of the Russian Musical Society. In September of the same year, Musical Classes were transformed into the Moscow Conservatory. Its official opening was scheduled for September 1. The directorate organized a big celebration: a public prayer was followed by an official dinner where many attendees gave solemn speeches. Tchaikovsky also took the floor. He wished success and prosperity to the conservatory and then mentioned that he believed the first music that had to be played at the new classes was that of Mikhail Glinka — an outstanding Russian genius. Tchaikovsky himself played the overture from Ruslan and Ludmila, which made a good impression on all participants.

From the very first days, Nikolai Rubinstein was looking after Pyotr Tchaikovsky: he accommodated Tchaikovsky at his apartment, tried to provide him with everything necessary, assisted with networking. It was Rubinstein who set up the composer’s meeting with Peter Jurgenson who owned a publishing firm and later published all of Tchaikovsky’s works.

Researchers said Pyotr Tchaikovsky was initially scared of working at the conservatory as he was a very shy person. However, he soon became friends with the students and started to invest a lot of time and effort into teaching. There were hardly any study guides on the theory of music at the time. The composer himself translated European handbooks, including François-Auguste Gevaert’s Handbook for Instrumentation, Johann Christian Lobe’s Catechism Of Music, and Robert Schumann’s Advice to Young Musicians. Tchaikovsky also created his own Manual of Harmony for his students. Back then, a common thing to say in Moscow was that any C-student from the Moscow Conservatory would outshine any A-student from the Saint Petersburg Conservatory because Tchaikovsky was teaching in the former one.

The composer worked at the conservatory for 11 years. He did, however, always confess that it weighed down on him. What helped the composer was the support of the patroness of art Nadezhda von Meck: she loved his music and offered financial assistance, which allowed him to quit teaching and devote himself to composing music. Tchaikovsky later said: “I will always be a bad teacher because I see each of my students as an enemy that exists just to torment me”. His students had a different opinion, though: they cherished the warmest memories of the professor.

A photo of the Conservatory’s founder Nikolai Rubinstein is in the very center, at the top of the picture. He remained the institution’s director until his death in 1881. A photograph of Pyotr Tchaikovsky occupies an honorable spot, to the right of the director.

Tchaikovsky came to Moscow in January 1866 when he was offered to teach the theory of music at Musical Classes of the Russian Musical Society. In September of the same year, Musical Classes were transformed into the Moscow Conservatory. Its official opening was scheduled for September 1. The directorate organized a big celebration: a public prayer was followed by an official dinner where many attendees gave solemn speeches. Tchaikovsky also took the floor. He wished success and prosperity to the conservatory and then mentioned that he believed the first music that had to be played at the new classes was that of Mikhail Glinka — an outstanding Russian genius. Tchaikovsky himself played the overture from Ruslan and Ludmila, which made a good impression on all participants.

From the very first days, Nikolai Rubinstein was looking after Pyotr Tchaikovsky: he accommodated Tchaikovsky at his apartment, tried to provide him with everything necessary, assisted with networking. It was Rubinstein who set up the composer’s meeting with Peter Jurgenson who owned a publishing firm and later published all of Tchaikovsky’s works.

Researchers said Pyotr Tchaikovsky was initially scared of working at the conservatory as he was a very shy person. However, he soon became friends with the students and started to invest a lot of time and effort into teaching. There were hardly any study guides on the theory of music at the time. The composer himself translated European handbooks, including François-Auguste Gevaert’s Handbook for Instrumentation, Johann Christian Lobe’s Catechism Of Music, and Robert Schumann’s Advice to Young Musicians. Tchaikovsky also created his own Manual of Harmony for his students. Back then, a common thing to say in Moscow was that any C-student from the Moscow Conservatory would outshine any A-student from the Saint Petersburg Conservatory because Tchaikovsky was teaching in the former one.

The composer worked at the conservatory for 11 years. He did, however, always confess that it weighed down on him. What helped the composer was the support of the patroness of art Nadezhda von Meck: she loved his music and offered financial assistance, which allowed him to quit teaching and devote himself to composing music. Tchaikovsky later said: “I will always be a bad teacher because I see each of my students as an enemy that exists just to torment me”. His students had a different opinion, though: they cherished the warmest memories of the professor.