Vasily Grigoryevich Ruban was born into a family of a petty nobleman in Belgorod. He entered the Kyiv-Mohyla Theological Academy but left for Moscow two years later. There he graduated from the Slavic Greek Latin Academy and then Moscow University, where he was especially enthusiastic about foreign languages such as Greek, Latin, German, French, and Tatar; later he mastered Turkish and Polish.

In 1761, soon after graduating from the university, he published his literary translation of the Latin text “Papiria of a Roman Child, Witty Fiction and Silence” in “Poleznoye uveseleniye” (Useful Amusement) — the moderately conservative journal of Mikhail Matveyevich Kheraskov.

In 1764, he became the secretary of Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin for the next eighteen years. Ruban’s literary legacy is vast and varied. Most of it consists of various odes and laudatory inscriptions. Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich conveyed the opinion of his contemporaries by saying unflattering things about Ruban, describing him as a “selfish panegyrist” and a “typical metromaniac” on the verge of destituteness.

Vasily Ruban actively collaborated with the following magazines: “Dobroye namereniye” (Good Intention) by Vasily Demyanovich Sankovsky, “Truten” (Drone Bee) and “Zhivopisets” (Painter) by Nikolay Ivanovich Novikov, “Parnassky shchepetylnik” (Parnassian Mercer) by Mikhail Dmitrieyvich Chulkov, “Rastushchyi vinograd” (Growing Grapes) by Yevgeny Borisovich Syreyshchikov, “Sankt-Peterburgskyi vestnik” (Saint Petersburg Herald) by Lev Logginovich Kambek. Ruban’s attempts to publish his own magazines (“Ni to, ni syo” (Neither This nor That) and “Trudolyubivy muravey” (Hardworking Ant)) were unsuccessful. “Ni to, ni syo”, which was intended by the publisher “to oblige the public”, lasted less than six months.

Vasily Ruban’s historical and narrative works, which include works on geography and statistics and somewhat of an anthology called “Old and New”, are of particular interest.

Ruban’s most successful contribution is considered to be his translation experiments. He was among the first Russian poets who translated ancient authors: Virgil, Ovid, Seneca, and Horace. He also translated seven works by Voltaire and collaborated as a translator from German and French with Nikolay Novikov — the publisher of the “Truten” and “Zhivopisets” magazines.

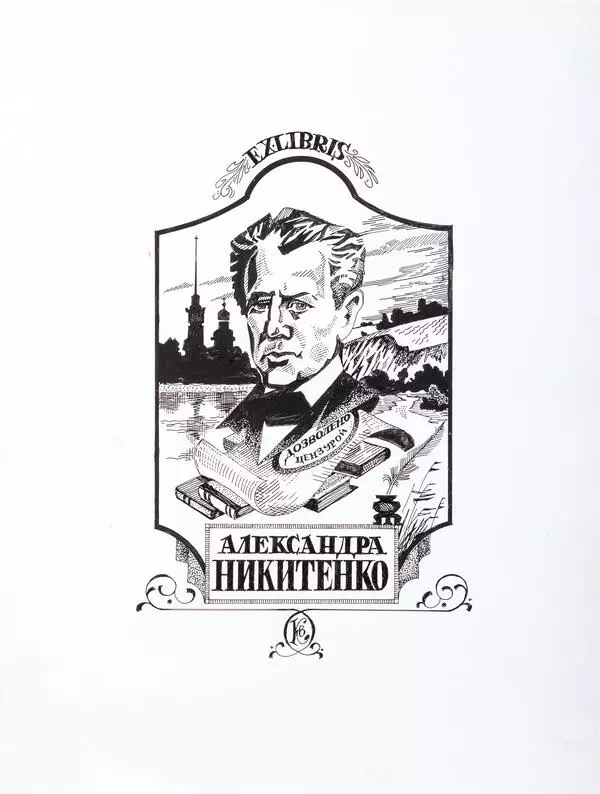

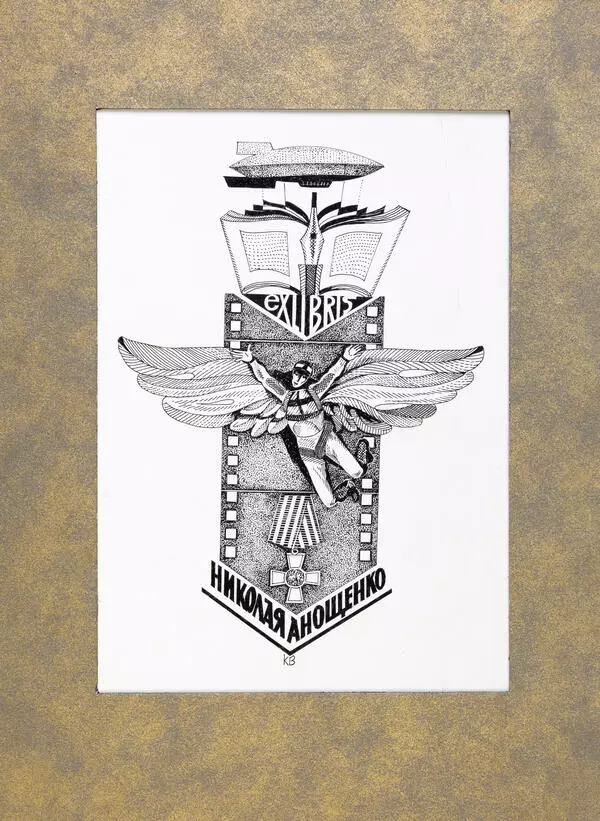

It is significant that in the center of Vasily Ruban’s bookplate the artist Vladimir Vladimirovich Kozmin placed the inscription that reads “To Prince Potemkin.” It serves as an accurate reflection of the poet’s position, who considered his patrons as the center of his work.

In 1761, soon after graduating from the university, he published his literary translation of the Latin text “Papiria of a Roman Child, Witty Fiction and Silence” in “Poleznoye uveseleniye” (Useful Amusement) — the moderately conservative journal of Mikhail Matveyevich Kheraskov.

In 1764, he became the secretary of Grigory Alexandrovich Potemkin for the next eighteen years. Ruban’s literary legacy is vast and varied. Most of it consists of various odes and laudatory inscriptions. Grand Duke Nicholas Mikhailovich conveyed the opinion of his contemporaries by saying unflattering things about Ruban, describing him as a “selfish panegyrist” and a “typical metromaniac” on the verge of destituteness.

Vasily Ruban actively collaborated with the following magazines: “Dobroye namereniye” (Good Intention) by Vasily Demyanovich Sankovsky, “Truten” (Drone Bee) and “Zhivopisets” (Painter) by Nikolay Ivanovich Novikov, “Parnassky shchepetylnik” (Parnassian Mercer) by Mikhail Dmitrieyvich Chulkov, “Rastushchyi vinograd” (Growing Grapes) by Yevgeny Borisovich Syreyshchikov, “Sankt-Peterburgskyi vestnik” (Saint Petersburg Herald) by Lev Logginovich Kambek. Ruban’s attempts to publish his own magazines (“Ni to, ni syo” (Neither This nor That) and “Trudolyubivy muravey” (Hardworking Ant)) were unsuccessful. “Ni to, ni syo”, which was intended by the publisher “to oblige the public”, lasted less than six months.

Vasily Ruban’s historical and narrative works, which include works on geography and statistics and somewhat of an anthology called “Old and New”, are of particular interest.

Ruban’s most successful contribution is considered to be his translation experiments. He was among the first Russian poets who translated ancient authors: Virgil, Ovid, Seneca, and Horace. He also translated seven works by Voltaire and collaborated as a translator from German and French with Nikolay Novikov — the publisher of the “Truten” and “Zhivopisets” magazines.

It is significant that in the center of Vasily Ruban’s bookplate the artist Vladimir Vladimirovich Kozmin placed the inscription that reads “To Prince Potemkin.” It serves as an accurate reflection of the poet’s position, who considered his patrons as the center of his work.