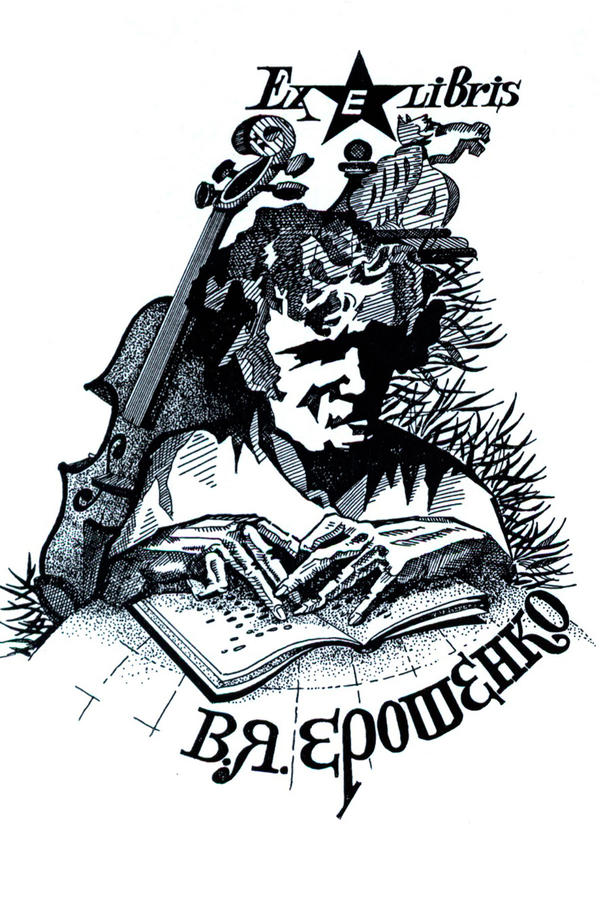

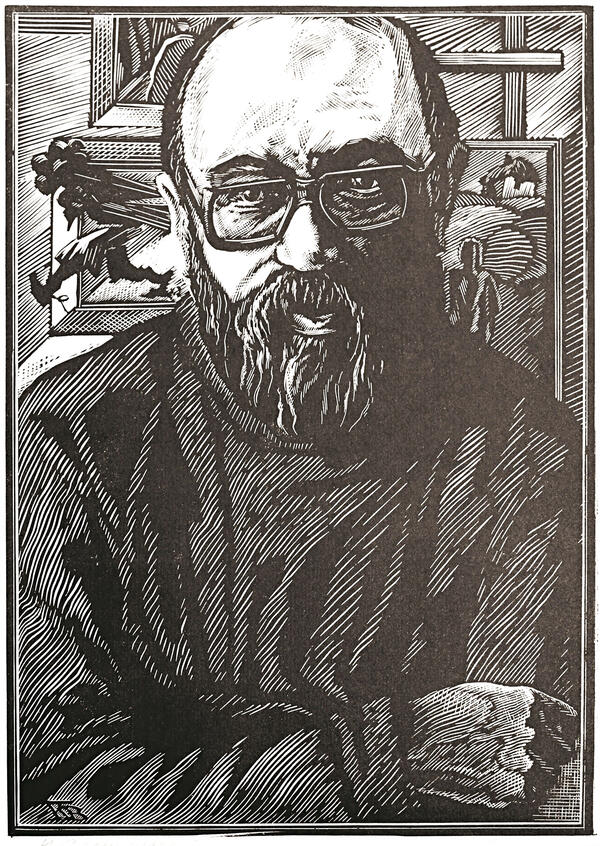

Vasily Yakovlevich Yeroshenko was born in 1890 in the sloboda of Obukhovka, Starooskolsky District. At the age of four, he contracted measles and, as a result, became blind: “I left the sunny colorful world all in tears.”

At the age of 9, Vasily was accepted to a school at the Moscow Society for Blind Children, which was patronized by Empress Maria Feodorovna. After graduating from school, he began performing in Moscow as part of an orchestra. During one of his performances, he was noticed by Anna Nikolayevna Sharapova, who stood at the origins of the development of Esperanto in Russia and decided to teach this language to the young violinist.

In the winter of 1912, on his own, Yeroshenko went to the English Royal College for the Blind, studied the basics of European typhlopedagogy, and two years later went to the School for the Blind in Tokyo. After living there for a year and a half, he wrote his first works in Japanese — “It’s Raining” and “The Tale of a Paper Lantern”. Yeroshenko became close to the circle of Japanese writers and began to write fairy tales and sketches for magazines. According to playwright Ujaku Akita, he was “the first Russian to win the hearts of the Japanese”.

Yeroshenko traveled to many European and Asian countries, was interested in local folklore, literature, and philosophy, and was also engaged in typhlopedagogy. Between 1919 and 1921, he taught the Russian culture at the University of Tokyo but then was forced to leave due to allegations of his spying for the Bolsheviks. The martial law prevented him from leaving the Far East, so Yeroshenko spent about three more years in China: he taught students in Beijing, continued writing, and became friends with the Chinese writer Lu Xun.

After returning to Moscow, he then traveled to Chukotka, Yakutia, Karelia, Donbas, Kharkiv, and Nizhny Novgorod. In Turkmenistan, Yeroshenko founded a boarding school for blind children and worked there. He also compiled the Braille alphabet in the Turkmen language.

In the early 1950s, the terminally ill Vasily Yeroshenko returned to Obukhovka and devoted himself to literature. His legacy includes his own and translated stories, fairy tales, poems, articles, sketches, and plays.

Vasily Yeroshenko died, deprived of his pension and due care. Boris Akunin said that this talented writer, translator, and teacher “was forgotten by his homeland, which in truth never really knew him.” The writer was rediscovered only after his death.

At the age of 9, Vasily was accepted to a school at the Moscow Society for Blind Children, which was patronized by Empress Maria Feodorovna. After graduating from school, he began performing in Moscow as part of an orchestra. During one of his performances, he was noticed by Anna Nikolayevna Sharapova, who stood at the origins of the development of Esperanto in Russia and decided to teach this language to the young violinist.

In the winter of 1912, on his own, Yeroshenko went to the English Royal College for the Blind, studied the basics of European typhlopedagogy, and two years later went to the School for the Blind in Tokyo. After living there for a year and a half, he wrote his first works in Japanese — “It’s Raining” and “The Tale of a Paper Lantern”. Yeroshenko became close to the circle of Japanese writers and began to write fairy tales and sketches for magazines. According to playwright Ujaku Akita, he was “the first Russian to win the hearts of the Japanese”.

Yeroshenko traveled to many European and Asian countries, was interested in local folklore, literature, and philosophy, and was also engaged in typhlopedagogy. Between 1919 and 1921, he taught the Russian culture at the University of Tokyo but then was forced to leave due to allegations of his spying for the Bolsheviks. The martial law prevented him from leaving the Far East, so Yeroshenko spent about three more years in China: he taught students in Beijing, continued writing, and became friends with the Chinese writer Lu Xun.

After returning to Moscow, he then traveled to Chukotka, Yakutia, Karelia, Donbas, Kharkiv, and Nizhny Novgorod. In Turkmenistan, Yeroshenko founded a boarding school for blind children and worked there. He also compiled the Braille alphabet in the Turkmen language.

In the early 1950s, the terminally ill Vasily Yeroshenko returned to Obukhovka and devoted himself to literature. His legacy includes his own and translated stories, fairy tales, poems, articles, sketches, and plays.

Vasily Yeroshenko died, deprived of his pension and due care. Boris Akunin said that this talented writer, translator, and teacher “was forgotten by his homeland, which in truth never really knew him.” The writer was rediscovered only after his death.