The part of a rural house depicted on a painting of Pavel Sudakov can be called traditional and belonging to the beginning of the 20th century only at first sight. Upon attentive inspection, it is not difficult to guess that this is not a house of the patriarchal peasant family, but a house of the average collective farmer’s family in late 1970s — early 1980s.

On its face, there is all attributes of a rural house: Russian stove, samovar, other poor kitchen utensil, and even a homespun doormat. But this is only at the first sight. The samovar seen in the right half of the painting isn’t that copper and usually three-core ‘king of the table’, but a cheap industrially manufactured nickelplated samovar that was supposedly purchased in a local village store.

The dishes standing on a stove are also far from traditional rural kitchen utensil: these pan and container are both enamel, which are used by both villagers and urbanites. If you look carefully, you can also notice the Russia-specific samovar in the left half of the painting. It’s dark, covered with patina, stands in the corner behind the stove and probably isn’t used for long.

The only item not in line with that interior is the spinning wheel in the center of the room. How did this crudely made item that clearly is not made in the 20th century ended up here and why is it in the center of the room and not somewhere under the leads, as expected for any old unneeded junk is anybody’s guess. This spinning wheel is clearly in a working order, even though presently there is no wool or spool of thread on it. Most likely, by depicting it in the painting’s center, the painter wanted to express the connection between generations for a viewer and a fact that, despite the new everyday objects, the Russian rusticity remained substantially the same.

The same thing is expressed by the big Russian stove. It was called the foster mother in Rus’ for a good reason: it heated a house, cooked meal for the whole family, and could replace a bath-house during winter. The fact of a stove still serving the same function can be observed by a bunch of drying mushrooms on it.

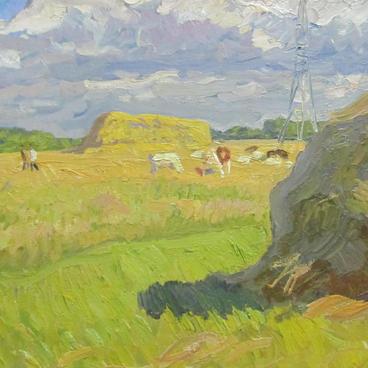

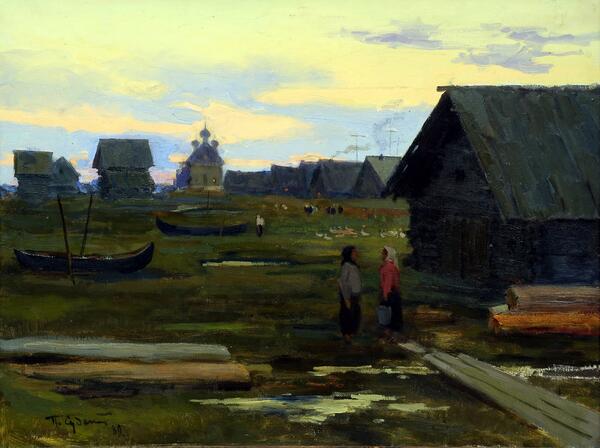

The painter of this art is Pavel Fyodorovich Sudakov, a people’s artist and one of the prominent representatives of socialist realism in painting. He was born three years before the Revolution into the family of Moscow workers. After finishing seven grades of high school, he enrolled in the factory-and-works college, and received basic artistic education in the Moscow Artists Union. The war prevented his further education: Pavel Fyodorovich volunteered for the front line, but didn’t reach Berlin. In late 1943, he was recalled to Moscow by a special order and was appointed as the head of the art studio of border forces.

After an army discharge in 1947, Sudakov was accepted in The Artists' Union of the USSR, travelled across Russia, painted many historical arts, portraits, landscapes and still life. He died in 2010 and is buried in Moscow.

On its face, there is all attributes of a rural house: Russian stove, samovar, other poor kitchen utensil, and even a homespun doormat. But this is only at the first sight. The samovar seen in the right half of the painting isn’t that copper and usually three-core ‘king of the table’, but a cheap industrially manufactured nickelplated samovar that was supposedly purchased in a local village store.

The dishes standing on a stove are also far from traditional rural kitchen utensil: these pan and container are both enamel, which are used by both villagers and urbanites. If you look carefully, you can also notice the Russia-specific samovar in the left half of the painting. It’s dark, covered with patina, stands in the corner behind the stove and probably isn’t used for long.

The only item not in line with that interior is the spinning wheel in the center of the room. How did this crudely made item that clearly is not made in the 20th century ended up here and why is it in the center of the room and not somewhere under the leads, as expected for any old unneeded junk is anybody’s guess. This spinning wheel is clearly in a working order, even though presently there is no wool or spool of thread on it. Most likely, by depicting it in the painting’s center, the painter wanted to express the connection between generations for a viewer and a fact that, despite the new everyday objects, the Russian rusticity remained substantially the same.

The same thing is expressed by the big Russian stove. It was called the foster mother in Rus’ for a good reason: it heated a house, cooked meal for the whole family, and could replace a bath-house during winter. The fact of a stove still serving the same function can be observed by a bunch of drying mushrooms on it.

The painter of this art is Pavel Fyodorovich Sudakov, a people’s artist and one of the prominent representatives of socialist realism in painting. He was born three years before the Revolution into the family of Moscow workers. After finishing seven grades of high school, he enrolled in the factory-and-works college, and received basic artistic education in the Moscow Artists Union. The war prevented his further education: Pavel Fyodorovich volunteered for the front line, but didn’t reach Berlin. In late 1943, he was recalled to Moscow by a special order and was appointed as the head of the art studio of border forces.

After an army discharge in 1947, Sudakov was accepted in The Artists' Union of the USSR, travelled across Russia, painted many historical arts, portraits, landscapes and still life. He died in 2010 and is buried in Moscow.