The mantel clock was not only a device for telling time, but also a piece of applied and decorative art.

According to researchers, the first mantel clock appeared in the mid-17th century in France, where the work of watchmakers was patronized personally by the “Sun King” Louis XIV. From there, a decade later, this interior piece made its way to England. Today, most of such exhibits, which are preserved in Russian museums, belong to the 18th and 19th centuries.

The art historian Oksana Viktorovna Zhernovnikova writes, “Before their [mantel clocks] advent, fireplaces did not have mantel pieces for clocks. The design and decor of mantel clocks echoed the decoration of the fireplaces themselves, for which marble, bronze and ceramics were used. The clocks were made in various styles: baroque, rococo, aux sauvages…, empire. The figurines on the clocks depicted biblical themes, scenes from ancient mythology, romantic or galante scenes. To decorate the clock, Egyptian and Greek decorative patterns, figures of cherubs, satyrs and cupids were used. The change of epochs and styles in the history of art influenced the shape of clocks, the abundance and type of decorative elements used in their design.“

The clock on display at the museum is a “barrel” with a round dial, which is located on a boat with a sail. Next to it is a figure of a young man in a round hat and short pants. He has a net slung over his shoulder. The lower part of the exhibit is an oval-shaped pedestal with relief pattern on the front side.

The clock is cast of spelter. In the 19th century, when the exhibit was created, factory production began to actively develop. There was a transition from artisanal labor in watchmaking workshops to mechanized labor in watch factories. Mass-produced watches came to the market.

Spelter is the common name for alloys of various non-ferrous metals: copper, zinc, nickel, tin; sometimes a mixture of zinc with lead and iron. There is no exact formula for the alloy. The most common metal was considered to be zinc and its alloys, which were used in the art industry between the 19th and the first third of the 20th century as substitutes for bronze or silver alloys. In this case, spelter and casting are complemented by enamel and gilding.

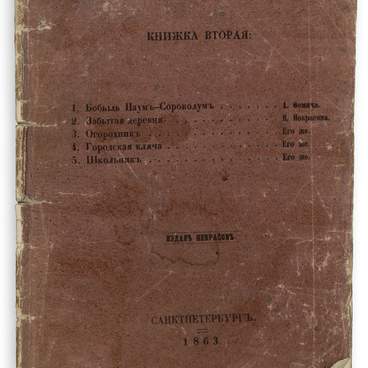

According to Vera Andreeva, the niece of the poet

Nikolay Nekrasov, this mantel clock stood in the study of her mother Natalia

Pavlovna Nekrasova in the Manor House of the Karabikha estate.