Bodiskina Gora is a steep descent leading from Maxim Gorky Street to the Orlik River. This name came to Oryol in the late 18th century: Yakov Bodisco, a state councilor and the fifth-generation gentleman of the Russian branch of the ancient European family of Bodisco, built a house on the high left bank of the river. Bodisco served in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Later, after Oryol Governorate had been established by Catherine II, Bodisco became the chairman of the Oryol Civil Court and the marshal of the nobility of the governorate.

The centuries-old family went down in the history of Russia for one more reason: the nephews of the state councilor — Boris Bodisco and Mikhail Bodisco — were naval officers, who, among other members of the nobility, participated in the Decembrist Revolt that took place on Senate Square on December 26 [O.S. 14 December], 1825.

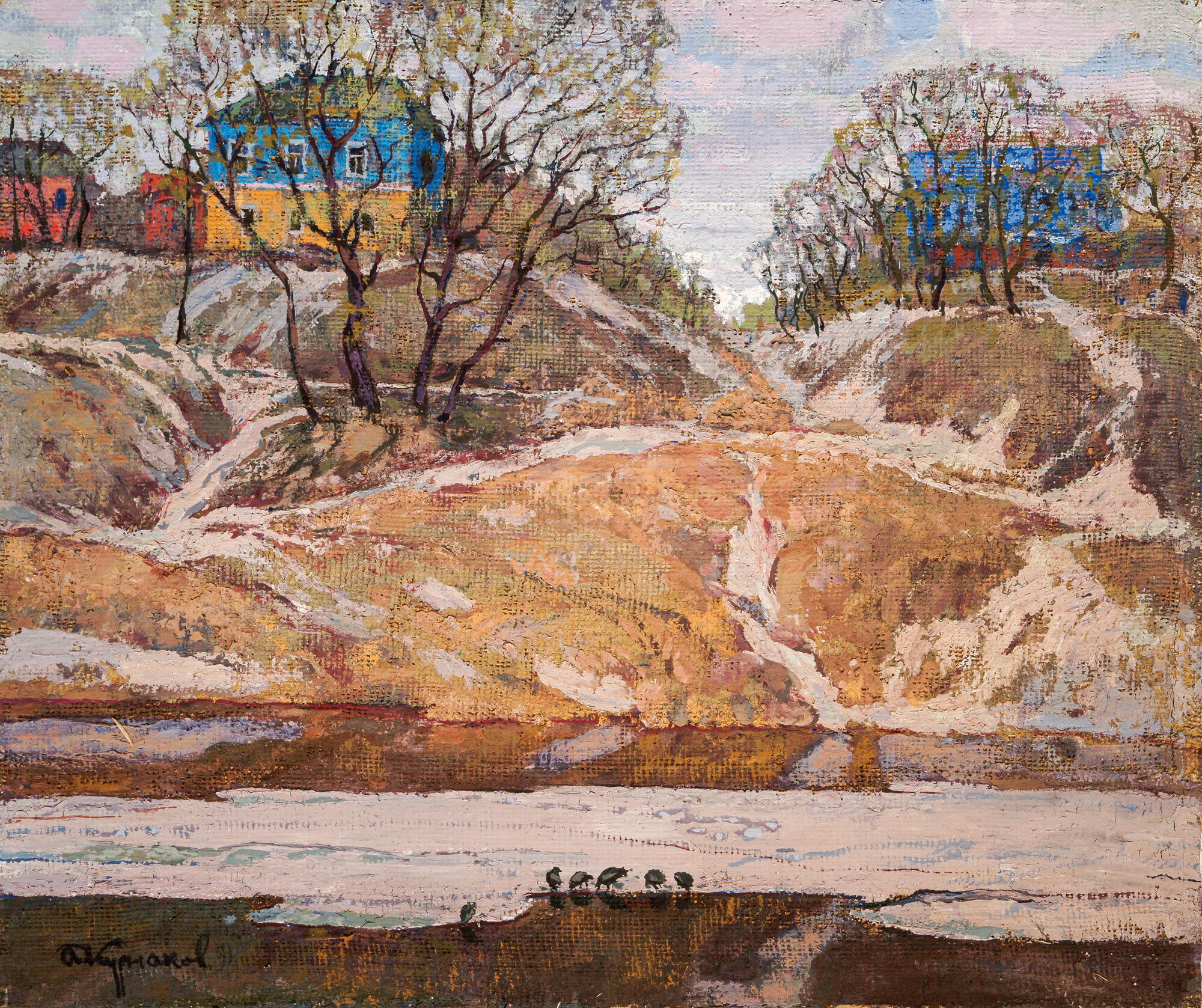

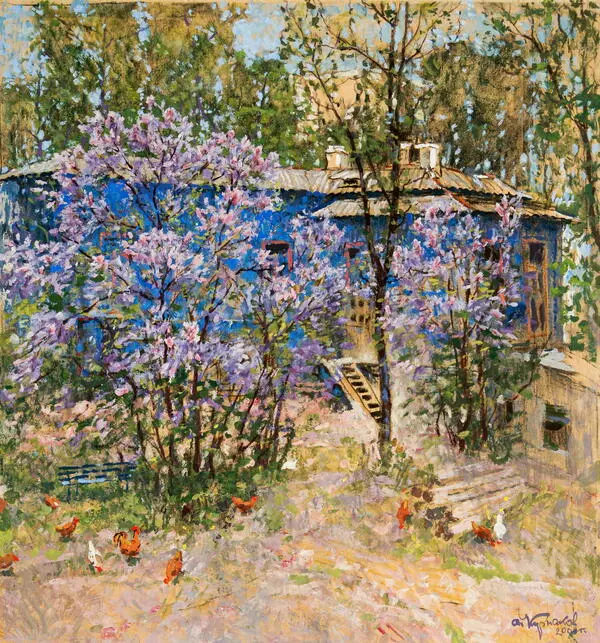

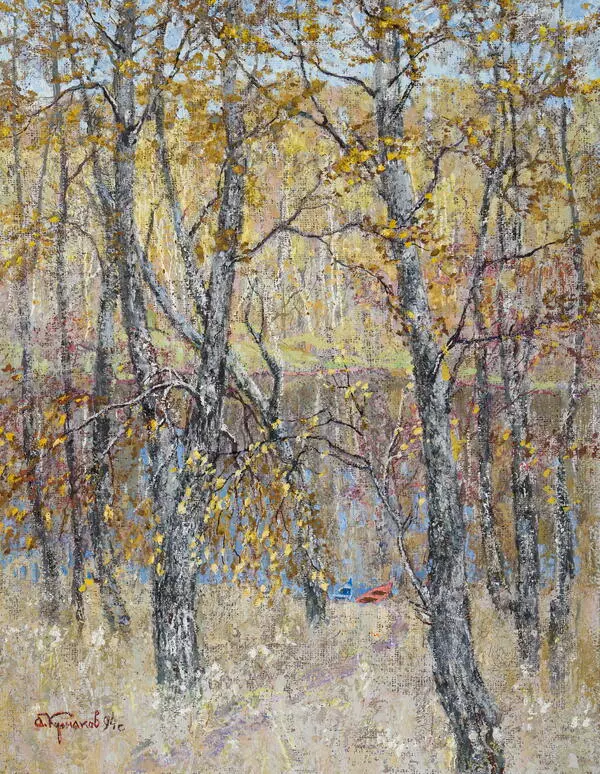

Andrey Kurnakov chose a cloudy day at the very beginning of spring to depict Bodiskina Gora. There is still snow in the hollows on the slope, the ice has not melted yet, but the river’s ice is already strewn with fairly big thawed patches. In the foreground, crows have settled comfortably on a dark block of ice. Behind the river, Kurnakov meticulously paints a steep, cliff bank, detailing its surface. The artist emphasizes the complex relief of a multileveled hill and the winding paths under the melting snow.

On the top of the hill, behind a few trees are houses, with clear outlines on the front turning into brownish blurriness in the depth of the painting. The yellow and blue mansion was most likely built in the 19th century according to the urban planning rules of that time — the lower floor is stone and the upper one is wooden. Even though the building is located where the nobility used to live, this is in fact a house of wealthy bourgeois who bought the land from the impoverished nobility. The only thing left from the Bodisco mansion is the name.

In the background, the artist depicts the gray and blue sky with mauve clouds, slightly tinted by the sun. The changing scenery of the sky with a white horizon seen through the crevice creates an impression of extra space and depth and adds movement and rhythm to the picture.

The centuries-old family went down in the history of Russia for one more reason: the nephews of the state councilor — Boris Bodisco and Mikhail Bodisco — were naval officers, who, among other members of the nobility, participated in the Decembrist Revolt that took place on Senate Square on December 26 [O.S. 14 December], 1825.

Andrey Kurnakov chose a cloudy day at the very beginning of spring to depict Bodiskina Gora. There is still snow in the hollows on the slope, the ice has not melted yet, but the river’s ice is already strewn with fairly big thawed patches. In the foreground, crows have settled comfortably on a dark block of ice. Behind the river, Kurnakov meticulously paints a steep, cliff bank, detailing its surface. The artist emphasizes the complex relief of a multileveled hill and the winding paths under the melting snow.

On the top of the hill, behind a few trees are houses, with clear outlines on the front turning into brownish blurriness in the depth of the painting. The yellow and blue mansion was most likely built in the 19th century according to the urban planning rules of that time — the lower floor is stone and the upper one is wooden. Even though the building is located where the nobility used to live, this is in fact a house of wealthy bourgeois who bought the land from the impoverished nobility. The only thing left from the Bodisco mansion is the name.

In the background, the artist depicts the gray and blue sky with mauve clouds, slightly tinted by the sun. The changing scenery of the sky with a white horizon seen through the crevice creates an impression of extra space and depth and adds movement and rhythm to the picture.