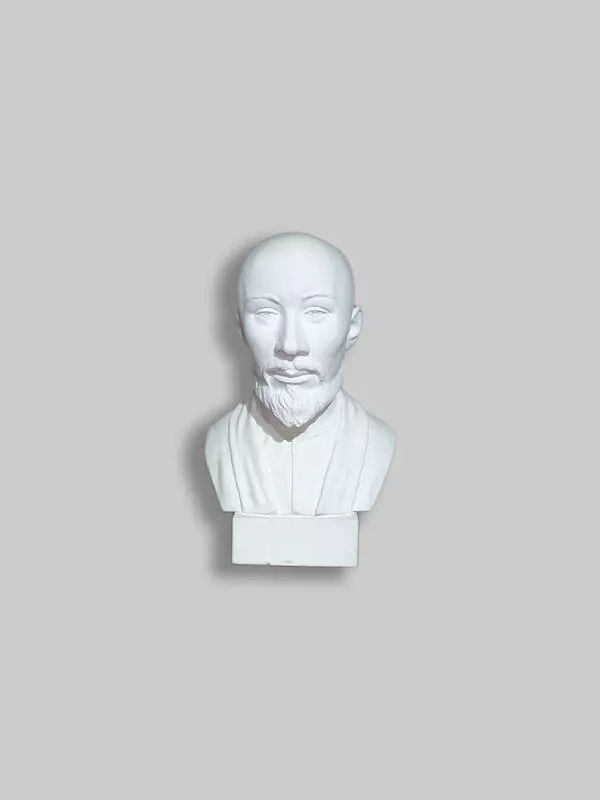

The anthropological sculptural facial reconstruction was performed using a woman’s skull found at the Solyony Dol (literally: Salty Lowland) burial ground. It is a chest-high portrait of a Caucasian-Mongoloid (Uraloid) woman, approximately 25 to 35 years old. The skull is artificially deformed, the upper part of the face is slightly elongated upward, the forehead is small, narrow, and straight, the eyebrows are arched, the eyes are slightly slanting, the eye sockets sit high, the nasal ridge is slightly depressed, the nose wings are wide, the jaws protrude slightly forward, the lips are plump, the chin is small and rounded, and the cheekbones are pronounced. The woman is wearing a pointed hat decorated with rows of round sequins, both single-piece and double. She is also wearing moon earrings. The flaps of the dress are decorated with rows of V-shaped overlays.

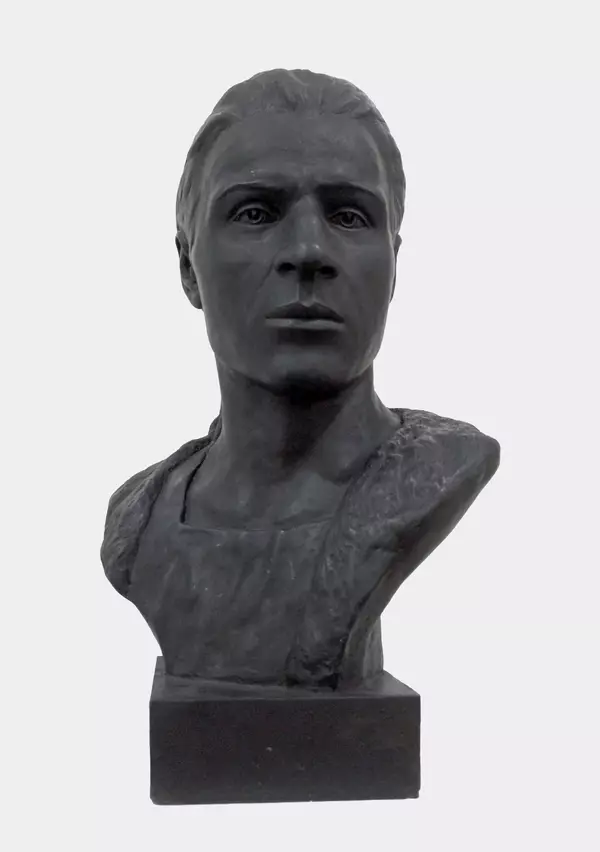

The sculptural facial reconstruction performed using the skull of a man is a chest-high portrait of a Caucasian male aged approximately between 45 and 55. His hair is partially shaved, slicked back, and braided. He has a large, wide, and sloping forehead. The eyebrows are narrow, almost straight, the eye sockets sit low, the nose is wide, straight, and slightly curved, with traces of an old fracture, the lips are thin, the mouth is large, the lower jaw is wide, the cheekbones are well defined, and the mustache has a horseshoe shape. The man has sideburns and a thick beard, a scar on his cheek, and traces of a stabbed wound on the top of his head. The skull had been artificially deformed.

The analysis of the man’s bones shows that he had an athletic build and multiple battle wounds: the fused cheekbone suggests a ragged scar on the cheek. There are also traces of a stabbed wound on the top of his head and a nose fracture. These injuries were not what caused the man’s death, but they indicate the “professional” military employment of men.

This historical period also had an interesting feature: the artificial deformation of the skull. This was usually done starting from an early age: a child’s skull would be artificially stretched by wrapping their head in a dense cloth, placing it between fixed boards or by systematically applying manual pressure. This custom was widespread among the Hunno-Sarmatians. About 70–80% of the population had deformed skulls. Perhaps the elongated shape of the skull was considered beautiful and served as a distinctive sign of nobility and honor, but over time became a wide-spread tradition.

Both anthropological reconstructions were performed by the Russian facial reconstruction expert and anthropologist Alexey Nechvaloda, a follower of Mikhail Gerasimov’s anthropological school. He worked to recreate the appearance of the Migration Period people in close cooperation with the archaeologist Sergei Botalov.

The sculptural facial reconstruction performed using the skull of a man is a chest-high portrait of a Caucasian male aged approximately between 45 and 55. His hair is partially shaved, slicked back, and braided. He has a large, wide, and sloping forehead. The eyebrows are narrow, almost straight, the eye sockets sit low, the nose is wide, straight, and slightly curved, with traces of an old fracture, the lips are thin, the mouth is large, the lower jaw is wide, the cheekbones are well defined, and the mustache has a horseshoe shape. The man has sideburns and a thick beard, a scar on his cheek, and traces of a stabbed wound on the top of his head. The skull had been artificially deformed.

The analysis of the man’s bones shows that he had an athletic build and multiple battle wounds: the fused cheekbone suggests a ragged scar on the cheek. There are also traces of a stabbed wound on the top of his head and a nose fracture. These injuries were not what caused the man’s death, but they indicate the “professional” military employment of men.

This historical period also had an interesting feature: the artificial deformation of the skull. This was usually done starting from an early age: a child’s skull would be artificially stretched by wrapping their head in a dense cloth, placing it between fixed boards or by systematically applying manual pressure. This custom was widespread among the Hunno-Sarmatians. About 70–80% of the population had deformed skulls. Perhaps the elongated shape of the skull was considered beautiful and served as a distinctive sign of nobility and honor, but over time became a wide-spread tradition.

Both anthropological reconstructions were performed by the Russian facial reconstruction expert and anthropologist Alexey Nechvaloda, a follower of Mikhail Gerasimov’s anthropological school. He worked to recreate the appearance of the Migration Period people in close cooperation with the archaeologist Sergei Botalov.