Alexander Grin (1880–1932) faced great difficulties both in his life and creative career. The “glittering world” of noble romantics in his works was always opposed by the real world. Grin looked for his place at sea, in the gold mines, and in various cities, but was met with disappointment wherever he went.

In 1902, Alexander Stepanovich Grinevsky (Grin’s real name) enlisted as a private in the 213th Oravais Reserve Infantry Battalion which was stationed near Penza. The writer recalled, “I hated military service from the very beginning. <…> When they tried to force me to clean the sergeant major’s boots… or to enter on duty out of turn, I would make such a scandal that… they considered disciplinary action.” Grinevsky was arrested for an attempt to desert the army and subsisted on a diet of bread and water for three weeks. However, after that, he escaped successfully.

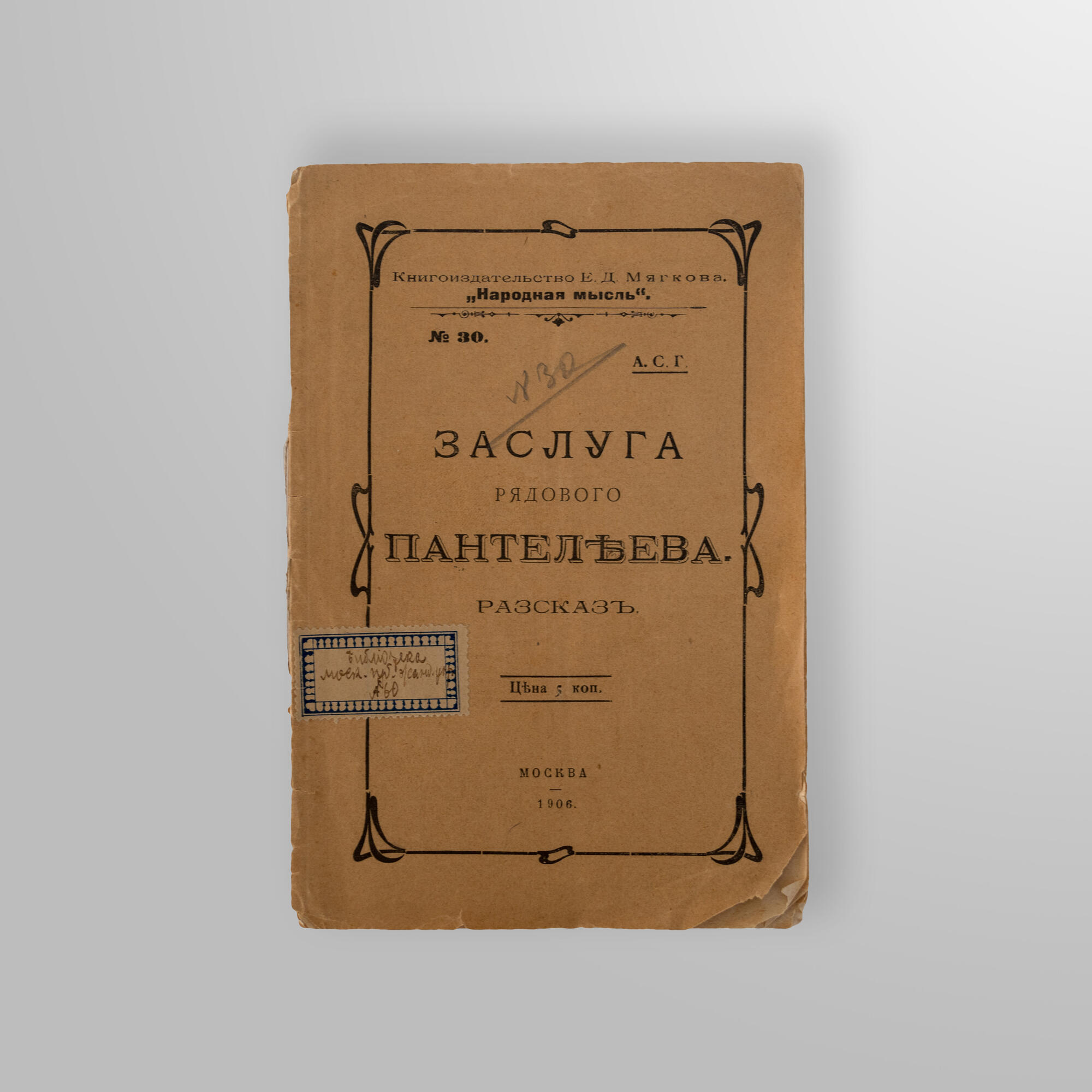

In 1903, Alexander Grin joined the revolutionary movement, was exiled to Tobolsk, and later escaped. In 1906, in Moscow, he wrote “The Merit of Private Panteleyev” — a proclamation addressed to members of the military participating in punishing their fellow soldiers. In that short story, the writer demonstrated the senseless cruelty of army life, the obsequiousness, and the loss of human dignity.

The story was published separately as a brochure, and the author received a handsome fee of 75 rubles. However, the books did not reach the readers as they were confiscated at the printing house and burned. Grinevsky was saved from being arrested once again by his unidentifiable signature “A.S.G.”

Years after Grin’s death, several surviving brochures were discovered. One of them was found in 1960 in the Moscow Gendarmerie, in the archive of the Department of Physical Evidence.

The displayed copy is marked with a library sticker of the Moscow Governorate Gendarmerie Department. In 1917, it was disbanded, and the books and documents were transferred to the State Archive of the RSFSR, and in 1925 to the Central Archive of the October Revolution. In 1941–1945, the archive was moved to the Volga region, then to the Urals and Siberia, and after the war back to Moscow. The papers had been kept in poor conditions, and some even suggested destroying or recycling all the “propaganda materials”. Although this did not happen, many papers were lost.

Grin’s brochure likely survived because it had been

lost. After all the twists and turns, it might have ended up in a private

collection or the Moscow State Library, and later in the Ilya Ulyanov Museum

and Reading Hall in Penza. In 1989, the book was transferred from the Ulyanov

Museum to the Literature Museum.