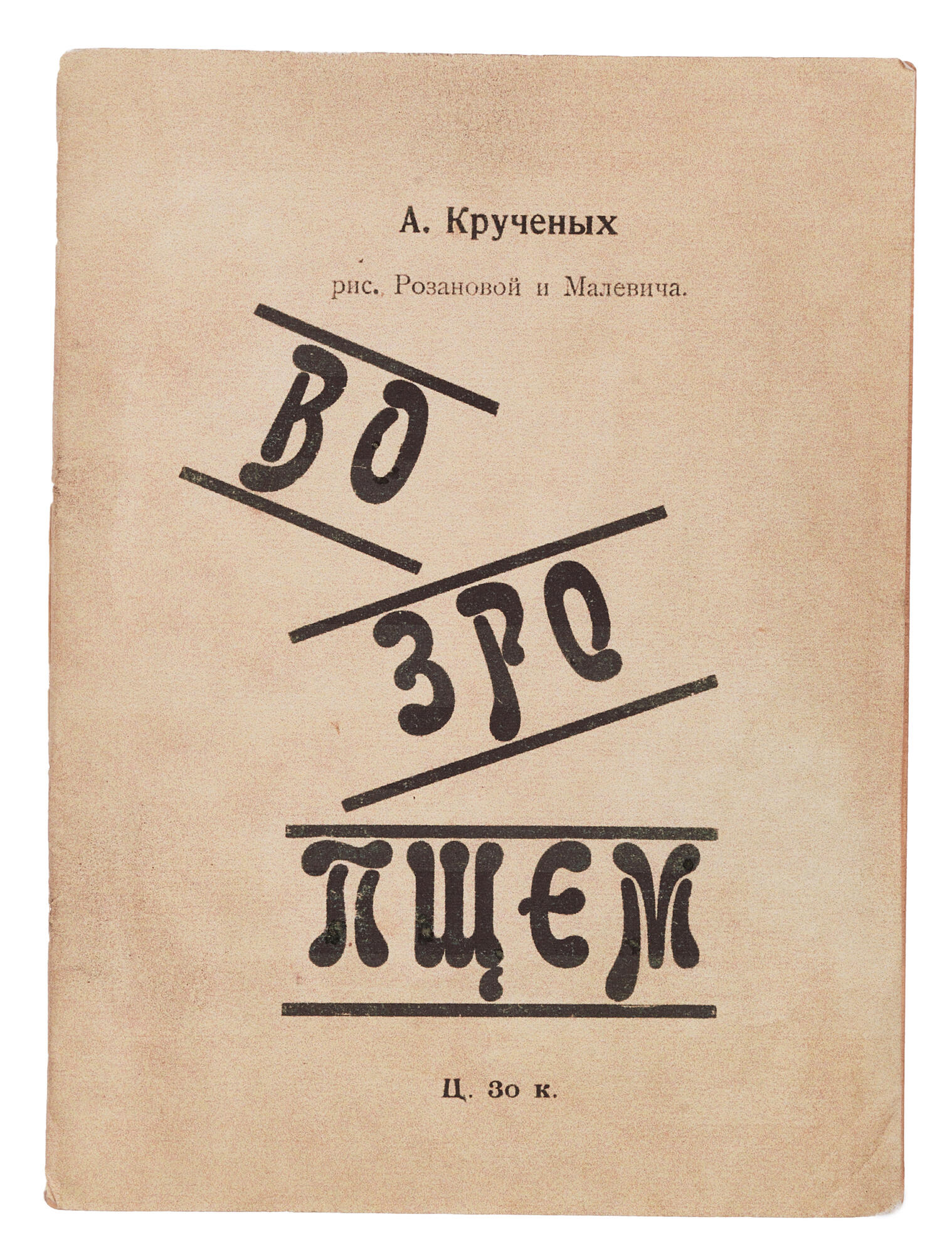

The poet Aleksey Yeliseyevich Kruchyonykh’s book “Let’s Grumble” was published in June 1913. The author was dubbed “the somber man of Russian literature”, as he was one of the most enigmatic and misunderstood Futurists.

The poet worked on creating a new, universally expressive language, the so-called “zaum”. The publicist Sergey Mikhailovich Tretyakov noted that “Kruchyonykh was the first to split the stale logs of words into fresh bars and splinters with his daring ax and breathe in with the indescribable love the fresh scent of speech wood — the language material.”

The collected works “Let’s Grumble” feature elements of the zaum language, which Aleksey Kruchyonykh wove into the context of his creations. The book includes four works: the poem “I Took a Needle Three Streets Long…”, the play “Deymo”, the lyrical poem “Inadvertently in Love Again Inopportunely He Uttered…”, and the critical sketch “The Outgrowth of Turgenev’s Love”.

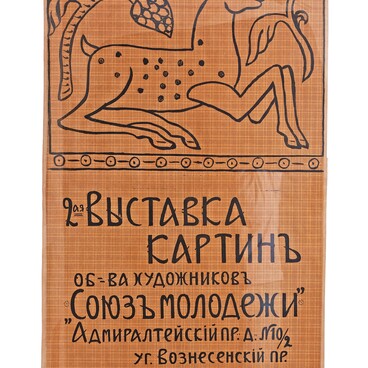

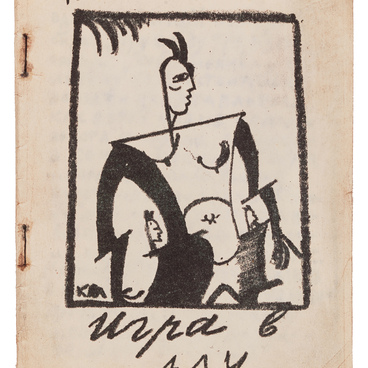

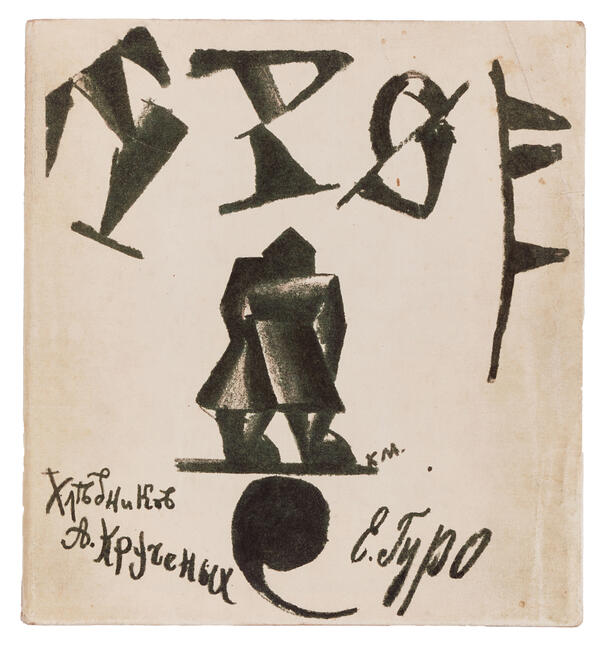

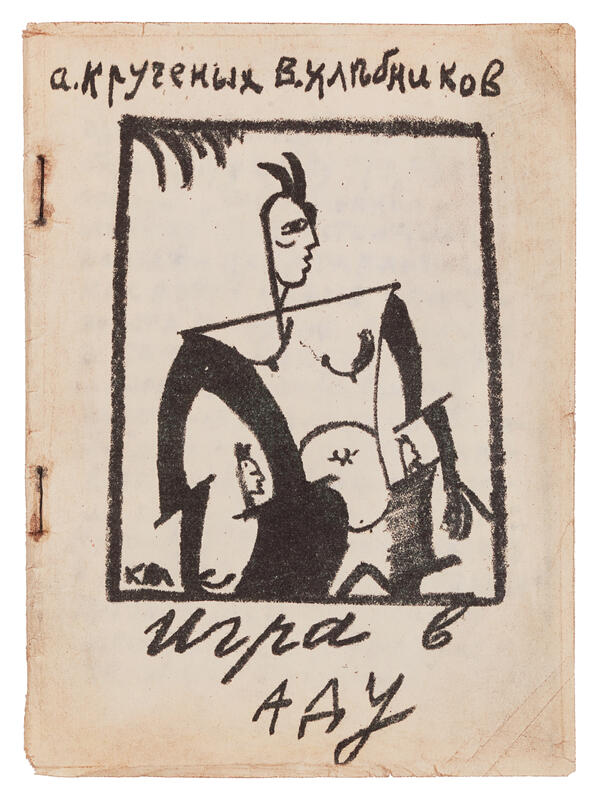

The poems are preceded by three lithographs on separate unnumbered pages of the book: “Peasant Woman Going to Fetch Water” and “Arithmetic” by Kazimir Malevich and “Face” by Olga Rozanova. Interestingly enough, Malevich’s lithographs were featured in many Futurist publications. Most often, as in the “Let’s Grumble”, such Cubo-Futurist pictorial compositions were not directly connected to the content.

The author dedicated the book to “O. Rozanova, the first artist of Petrograd.” The lines of the poem “Inadvertently in Love Again Inopportunely He Uttered…”, where the poet used the O initial for the name Olga, may hint at the nature of the relationship between the two.

Besides the lithograph “Face”, the book also contains a reproduction of Olga Rozanova’s painting “Café”. In the edition, it was titled “Shelter”. The researcher Nina Albertovna Guryanova noted that “The poet and the artist were creating an alter ego. Their dialogue went on nonstop in their correspondence, articles and their ‘hand-written’ books.”

Indeed, between 1913 and

1915, the poet and the artist worked together on hand-written books where the

text and illustrations supplemented each other. Between 1916 and 1918, during

Kruchyonykh’s stay in the Caucasus, they communicated through letters, making

Letterist books in which the text coincided with the images.