Isaac Levitan (August 30, 1860 - August 4, 1900) entered the history of art as an unsurpassed landscape painter, a glorifier of Russian expanses, a master of ‘mood landscape’. Strange as it may seem, neither the big fame, nor the possibility of a fairly detailed study of his biography (for example, by correspondence with famous contemporaries, including Anton Chekhov) allow us to fully comprehend the mystery of the artist’s creative genius. A haze of mystery and a halo of metaphors is surrounded by such a softly sounding surname Levitan.

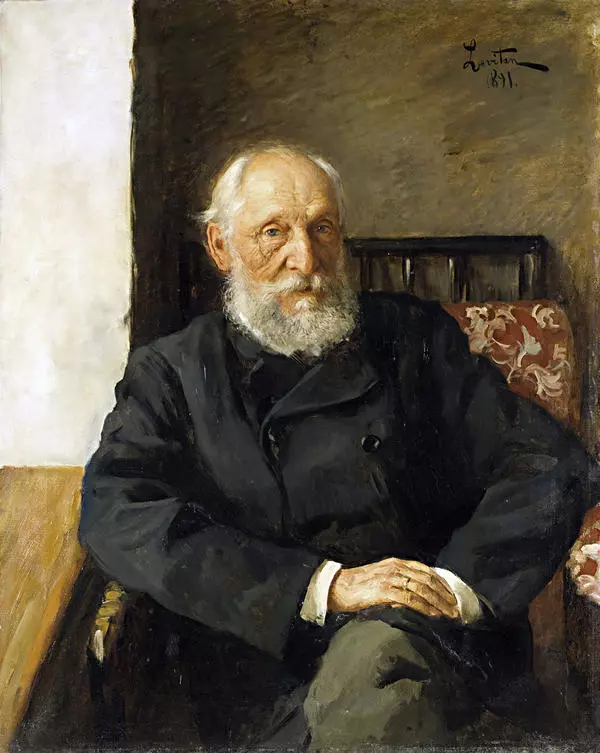

In 1891, when work on the canvas began, Levitan became a member of the Peredvizhniki Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions, and Moscow art patron Sergei Morozov provided him with a comfortable workshop in Trekhsvyatitelsky Lane. In this workshop, the famous painter V.Serov later painted the well-known portrait of the artist. Over the next two years, there was a break in the work on that canvas.

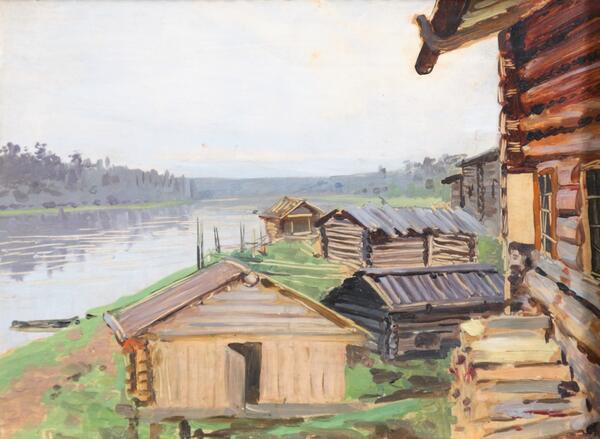

In 1892, the artist, as “the face of the Jewish faith”, will be forced to leave Moscow and live for some time in the Tver and Vladimir provinces. Very soon, thanks to the efforts of his friends, he was able to return to the capital. Nevertheless, he reflected his feelings in the expressively gloomy canvas “Vladimirka”, depicting the road along which convicts were driven to Siberia.

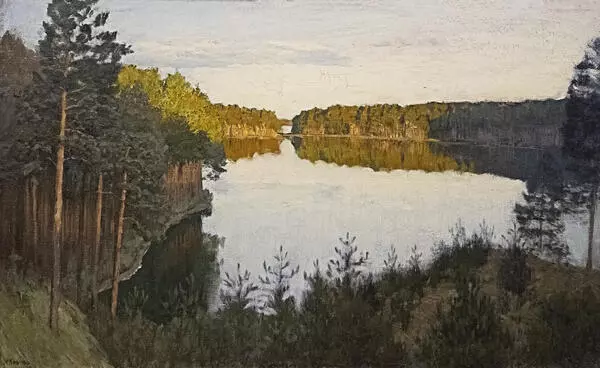

In 1894, the artist’s life was full of tragical love drama. The bitter feelings that took possession of Levitan were embodied in his work in a kind of dramatic trilogy, which included the aforementioned ‘Vladimirka’, the canvas ‘By the whirlpool’ and the emotionally powerful work ‘Above the Eternal Peace’. The painting ‘Above the Eternal Peace’ was presented to the public at the 22nd travelling exhibition in 1894, together with the ‘Evening Shadows’, which was already completely finished, but in a completely different mood.

There is no hint of hopelessness. On the contrary: the quiet, lyrical evening landscape, so typical of the central part of Russia, disposes to peace and contemplation. A strip of light in the center of the picture fills it with a bright palette of colors, joy, and awe of the beauty of a living, blooming world.

However, the unsolved personal motives of Levitan’s creation of such a magnificent pictorial metaphor, hiding behind the boundaries of the canvas, leave everyone the right to their own emotional interpretation of the work.

In 1891, when work on the canvas began, Levitan became a member of the Peredvizhniki Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions, and Moscow art patron Sergei Morozov provided him with a comfortable workshop in Trekhsvyatitelsky Lane. In this workshop, the famous painter V.Serov later painted the well-known portrait of the artist. Over the next two years, there was a break in the work on that canvas.

In 1892, the artist, as “the face of the Jewish faith”, will be forced to leave Moscow and live for some time in the Tver and Vladimir provinces. Very soon, thanks to the efforts of his friends, he was able to return to the capital. Nevertheless, he reflected his feelings in the expressively gloomy canvas “Vladimirka”, depicting the road along which convicts were driven to Siberia.

In 1894, the artist’s life was full of tragical love drama. The bitter feelings that took possession of Levitan were embodied in his work in a kind of dramatic trilogy, which included the aforementioned ‘Vladimirka’, the canvas ‘By the whirlpool’ and the emotionally powerful work ‘Above the Eternal Peace’. The painting ‘Above the Eternal Peace’ was presented to the public at the 22nd travelling exhibition in 1894, together with the ‘Evening Shadows’, which was already completely finished, but in a completely different mood.

There is no hint of hopelessness. On the contrary: the quiet, lyrical evening landscape, so typical of the central part of Russia, disposes to peace and contemplation. A strip of light in the center of the picture fills it with a bright palette of colors, joy, and awe of the beauty of a living, blooming world.

However, the unsolved personal motives of Levitan’s creation of such a magnificent pictorial metaphor, hiding behind the boundaries of the canvas, leave everyone the right to their own emotional interpretation of the work.