In 600 AD, ancient Chinese craftsmen began to create products that were highly durable with minimal subtlety. This is how the whole world learned about porcelain That material was an exceptional invention of the Chinese, which they did their best to keep secret. However, in 1300, Chinese porcelain plates began to appear gradually in European royal palaces. It was very expensive, so it was most often used not to serve dishes, but to decorate the interior. Only from the 17th century ‘tarel’ - the Russians quickly converted this word into ‘plate’ - began to become a household item and from the beginning of the 18th century it became simply irreplaceable in feasts.

However, the decorative life of the plate did not end there, but only began to develop. At the end of the 19th century, collecting decorative plates became fashionable. Service items in blue and white tones, as well as ancient and rare items, were a success. ‘Tarels’ in Russia were awarded to loyal tsarist servants for their special services. Such dishes were decorated with monograms and put in a prominent place in the house. Over time, commemorative plates began to be produced for various important events.

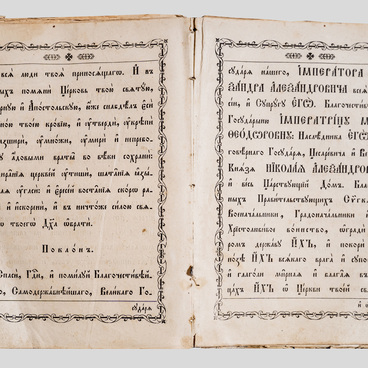

The limited release of plates was timed to coincide with the royal visit of Emperor Nicholas II and his spouse to France in 1896. At that time, many goods were produced in the Russian or pseudo-Russian style: Le Tsar soap, sweets with the Russian emblem or flag, dishes with tsars’ portraits, toys in the form of a Russian bear, as well as in the forms of the sovereign, empress and even Grand Duchess Olga. The tsar was portrayed by Maslenitsa “jumping devils”, the famous toy “man and bear” turned into tsar and Felix Fora. Advertising took advantage of the fashion: “Pink pills” were recommended to keep people healthy for the days of the tsar’s arrival; and on the backs of his portraits, which were handed out for free on the streets, advertisements for shoemakers and glovers were printed.

Similar plates are on display in the permanent exhibition of the Constantine Palace in St. Petersburg and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The plates are also presented in the catalog of souvenirs for the visit of Emperor Nicholas II to France, which was published in 1897.