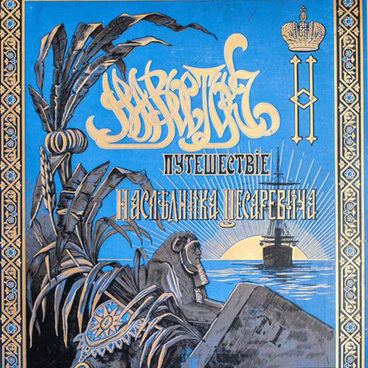

On July 10, 1891 future Emperor Nicholas II arrived to Tobolsk and visited the Provincial museum. Nikolay Lytkin, the curator of the exposition, conducted an excursion for him. For his interesting narrative about the collection, Tsesarevich gifted him gold studs and presented a precious signet ring to the librarian who showed him rare antique editions.

Vladimir Troynitsky, Tobolsk Governor, accompanied the Crown Prince during the excursion to the museum. On his request, Nicholas Alexandrovich put his name and date of visit on a plaque made of mammoth bone, which was later placed in the museum library under the portrait of the last Russian Emperor.

The plaque and the pen to it were made by Tobolsk craftsmen-bone carvers. By the 19th century, this сraft was prospering in Siberia. The fossil mammoth bone in these areas was rather difficult to extract. Besides, walrus fangs and cachalot teeth were a popular material at that time.

Siberians started bone carving as early as in the 17th century. Archeologists often find combs, figurines, chess pieces that related to that period. However, the pioneer bone carving workshops appeared only in the 18th century here. In 1721, Swedish officers who were captured during the Great Northern War were deported to Siberia. Many of them were practicing lathe bone-carving and taught other craftsmen. Turned snuffboxes, hairpins, brooches and crucifixes were of great demand. Bone carvers usually used to work alone or in small groups.

At the end of the 19th century, private bone-craving workshops appeared in Tobolsk. Their products were sold out not only in neighborhood provinces but also in Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, Kazan, Kiev and other large cities of the Russian Empire. In 1898, the works of Tobolsk craftsmen were awarded gold medal at the Franco-Russian exhibition hosted in Saint-Petersburg.

Vladimir Troynitsky, Tobolsk Governor, accompanied the Crown Prince during the excursion to the museum. On his request, Nicholas Alexandrovich put his name and date of visit on a plaque made of mammoth bone, which was later placed in the museum library under the portrait of the last Russian Emperor.

The rectangular plate and the bone pen, which Tsesarevich used to put his signature with, were placed in a glass showcase on a backing made of dark-blue velvet. The size of the plaques is not big – only 17.5×7 centimeters. It is decorated with an emblem of the Russian Empire – a crowned two-headed eagle. The pen is made in the form of goose quill.

The plaque and the pen to it were made by Tobolsk craftsmen-bone carvers. By the 19th century, this сraft was prospering in Siberia. The fossil mammoth bone in these areas was rather difficult to extract. Besides, walrus fangs and cachalot teeth were a popular material at that time.

Siberians started bone carving as early as in the 17th century. Archeologists often find combs, figurines, chess pieces that related to that period. However, the pioneer bone carving workshops appeared only in the 18th century here. In 1721, Swedish officers who were captured during the Great Northern War were deported to Siberia. Many of them were practicing lathe bone-carving and taught other craftsmen. Turned snuffboxes, hairpins, brooches and crucifixes were of great demand. Bone carvers usually used to work alone or in small groups.

At the end of the 19th century, private bone-craving workshops appeared in Tobolsk. Their products were sold out not only in neighborhood provinces but also in Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, Kazan, Kiev and other large cities of the Russian Empire. In 1898, the works of Tobolsk craftsmen were awarded gold medal at the Franco-Russian exhibition hosted in Saint-Petersburg.