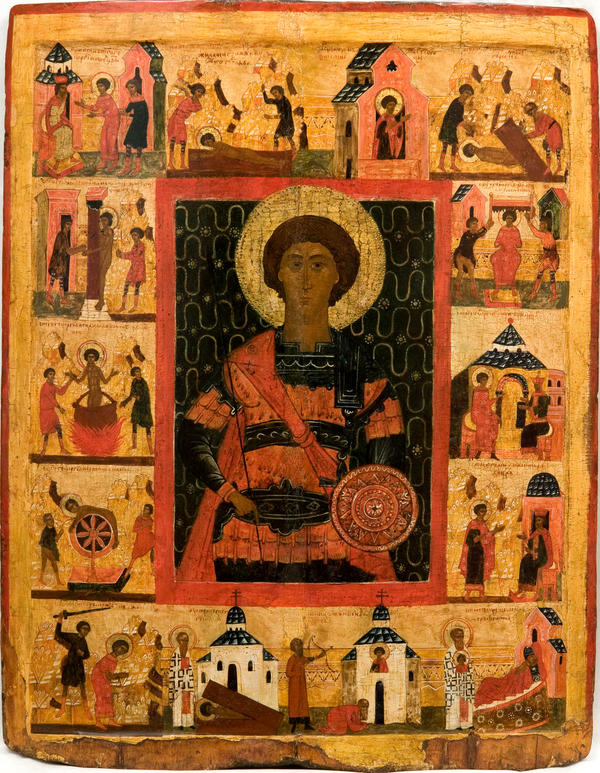

The image of Saint George is one of the most popular in the medieval Christian art. Starting from 10th-11th centuries, he has been mainly depicted in two ways - as a martyr or as a warrior. In the exhibited icon, Saint George is a warrior, with a red cloak on his shoulders, a spear in his right hand and a shield in the left. The image of George standing was widely spread in Byzantine, in the Balkans and in the Christian East. It has become characteristic of the Moscow iconographic tradition.

The centrepiece framed in red is occupied by the image of Saint George while the hagiographical border scenes around represent 14 separate episodes from his life. Starting from the upper left corner clockwise, they are placed in the following order: George being brought to king Dadianus, Torture by ox tendons, George in dungeon, Torture by board, George being cut with a saw, George in front of the Empress, George in front of the Emperor, Saracen’s healing by the icon of Saint George, Atrocity of a Saracen to the image of Saint George, Dormition of George, George being boiled in caldron, Decapitation, Slashing on the rack, George being lashed.

The icon is notable for the fact that in addition to the typical scenes of George’s martyrdom, there are two scenes of miracles produced by the icon of the saint, depicted in the episodes Saracen’s healing by the icon of Saint George and Atrocity of a Saracen to the image of Saint George. Such episodes with miracles by Christian saints bringing disgrace on infidels became popular in Russian iconography especially in Moscow in the 14th century.

The absence of inscription in the centerpiece is a peculiar feature of the icon whereas each episode around has an inscription at the top, in the Church Slavonic language. All of them are done in cinnabar. A quaint ornament in the central piece is also unusual as well as its blue background, which can be found either in ancient or more recent monuments of icon painting. There is a certain compositional disproportion in some fragments of the central image: the hand and the shield are too small. The episodes also have some peculiarities: the hills are painted with almost black shades and ornamental half shades. All these particularities, notwithstanding later repainting, suggest that the icon was made by a provincial master who followed the traditions of Russia North painting.

The centrepiece framed in red is occupied by the image of Saint George while the hagiographical border scenes around represent 14 separate episodes from his life. Starting from the upper left corner clockwise, they are placed in the following order: George being brought to king Dadianus, Torture by ox tendons, George in dungeon, Torture by board, George being cut with a saw, George in front of the Empress, George in front of the Emperor, Saracen’s healing by the icon of Saint George, Atrocity of a Saracen to the image of Saint George, Dormition of George, George being boiled in caldron, Decapitation, Slashing on the rack, George being lashed.

The icon is notable for the fact that in addition to the typical scenes of George’s martyrdom, there are two scenes of miracles produced by the icon of the saint, depicted in the episodes Saracen’s healing by the icon of Saint George and Atrocity of a Saracen to the image of Saint George. Such episodes with miracles by Christian saints bringing disgrace on infidels became popular in Russian iconography especially in Moscow in the 14th century.

The absence of inscription in the centerpiece is a peculiar feature of the icon whereas each episode around has an inscription at the top, in the Church Slavonic language. All of them are done in cinnabar. A quaint ornament in the central piece is also unusual as well as its blue background, which can be found either in ancient or more recent monuments of icon painting. There is a certain compositional disproportion in some fragments of the central image: the hand and the shield are too small. The episodes also have some peculiarities: the hills are painted with almost black shades and ornamental half shades. All these particularities, notwithstanding later repainting, suggest that the icon was made by a provincial master who followed the traditions of Russia North painting.