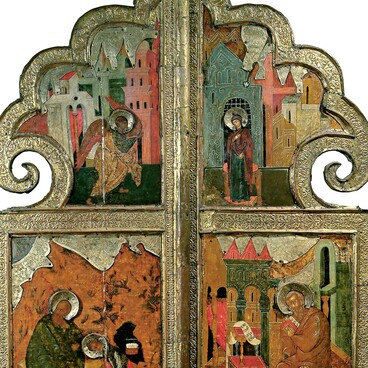

The icon of Saviour the Unsleeping Eye was painted by an unknown artist in the second half of the 17th century. The central piece of the composition is a bed with fancy-shaped legs and balusters, short poles looking like columns. Lying on the bed is Christ Emmanuel. In the background, the artist placed heavenly plants.

On the left of the bed, there is the Holy Mother standing in prayer. In her hands, she holds a scroll with the text of the prayer for Orthodox Christians. The Holy Mother’s attitude and the scroll in her hands point to her intercessory role associated with the idea of the non-sleeping God who will protect his people and expiate its sins with his blood. On the right of Christ, there is an angel holding a thin baton and a spherical mirror with Jesus’s initials. Soaring above the Saviour, there is another angel, holding the instruments of Christ’s passions, the spear and the stick with a sponge. The representation of the instruments lack details: they resemble two rods with a round and rhombic top. The upper part of the icon symbolizes heaven. In the heaven, there is the Lord Sabaoth, who blesses praying people with his both hands. In the upper corners of the icon, there is the sun and the moon.

The subject of the Saviour the Unsleeping Eye icon developed in Byzantine art in the early 14th century and was called “anapeson” (“reclining”). In Russia, the subject became widespread in the 12th century. The representation of the youth Emmanuel sleeping with his eyes open symbolizes indivisibility of the divine and human nature of the crucified and buried Saviour. The image of Christ, dead but “seeing all by Divinity”, was associated to believers with lines of the Psalms: “My help cometh from the Lord, which made heaven and earth… Behold, he that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep” (Psalm 121: 2, 4), which are often found on Saviour the Unsleeping Eye icons. A fragment of the same text can be found on the Murom icon as well.

In Russian art, the iconography of this image established in the mid-16th century. The icon is distinguished due to its bright colours based on a contrast between red-brown and blue shades. The features of the faces are drawn rather broadly due to a simplistic manner of painting.

On the left of the bed, there is the Holy Mother standing in prayer. In her hands, she holds a scroll with the text of the prayer for Orthodox Christians. The Holy Mother’s attitude and the scroll in her hands point to her intercessory role associated with the idea of the non-sleeping God who will protect his people and expiate its sins with his blood. On the right of Christ, there is an angel holding a thin baton and a spherical mirror with Jesus’s initials. Soaring above the Saviour, there is another angel, holding the instruments of Christ’s passions, the spear and the stick with a sponge. The representation of the instruments lack details: they resemble two rods with a round and rhombic top. The upper part of the icon symbolizes heaven. In the heaven, there is the Lord Sabaoth, who blesses praying people with his both hands. In the upper corners of the icon, there is the sun and the moon.

The subject of the Saviour the Unsleeping Eye icon developed in Byzantine art in the early 14th century and was called “anapeson” (“reclining”). In Russia, the subject became widespread in the 12th century. The representation of the youth Emmanuel sleeping with his eyes open symbolizes indivisibility of the divine and human nature of the crucified and buried Saviour. The image of Christ, dead but “seeing all by Divinity”, was associated to believers with lines of the Psalms: “My help cometh from the Lord, which made heaven and earth… Behold, he that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep” (Psalm 121: 2, 4), which are often found on Saviour the Unsleeping Eye icons. A fragment of the same text can be found on the Murom icon as well.

In Russian art, the iconography of this image established in the mid-16th century. The icon is distinguished due to its bright colours based on a contrast between red-brown and blue shades. The features of the faces are drawn rather broadly due to a simplistic manner of painting.