Until the 19th century, every Jewish community included a holy brotherhood, the Chevra Kadisha. It emerged along with a permanent synagogue and a cemetery at the time when the Jews began to live a settled life. The duties of the Chevra kadisha were to care for the sick, provide overnight accommodation for wayfarers, help the poor, as well as arrange funerals and mount gravestones.

According to Jewish tradition, the tombstones placed on graves were revered as shrines. They were both original and traditional in style, rich in decoration and varied in symbolism. Tombstones are used to study Jewish epigraphy — the science of inscriptions on stone — as well as the history of the Jewish arts.

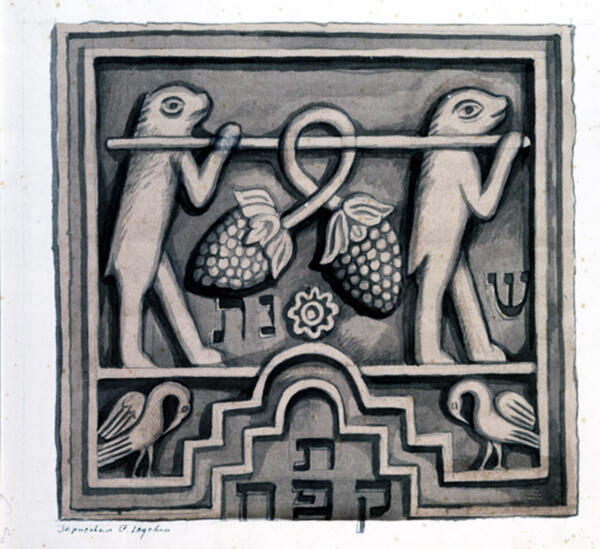

The main type of tombstone is a stela or matzevah, a vertical slab of stone. “Stela” in Greek means a “pillar”. The art of making stelae has been known since the Bronze Age, over 5,000 years. They vary depending on materials, religions, rituals and purposes. The sculptural reliefs on tombstones express people’s philosophical, religious and psychological ideas.

The images on Jewish tombstones repeat the drawings in the pinkas — the record books of the Jewish community — as well as the symbols of amulets against evil spirits, above all Lilith and Agrat bat Mahallat. The concise language of the signs conveyed the caste and clan affiliation of the deceased. Thus, ancient musical instruments or a jug were depicted on the grave of a Levite, a descendant of the Levi family, and a flock without a shepherd on the grave of a rabbi.

Hands over burning candles or only candles in Sabbath candlesticks were depicted over the graves of women, as lighting fires during domestic rites was their sacred duty. An open book may have been placed on the grave of an author of religious writings. A goose feather, alone or held in the hand, was on the grave of a scribe of sacred texts, scissors indicated a tailor’s grave, a chain or other jewelery — a jeweler’s one.

Death also had its own symbolism, marked by a broken vessel or boat, a broken candle, an overturned extinguished lamp, a fallen crown, or a broken branch. The epitaph, thanks to its emotionally expressive Hebrew lettering, was often the main decorative element of a tombstone.

According to Jewish tradition, the tombstones placed on graves were revered as shrines. They were both original and traditional in style, rich in decoration and varied in symbolism. Tombstones are used to study Jewish epigraphy — the science of inscriptions on stone — as well as the history of the Jewish arts.

The main type of tombstone is a stela or matzevah, a vertical slab of stone. “Stela” in Greek means a “pillar”. The art of making stelae has been known since the Bronze Age, over 5,000 years. They vary depending on materials, religions, rituals and purposes. The sculptural reliefs on tombstones express people’s philosophical, religious and psychological ideas.

The images on Jewish tombstones repeat the drawings in the pinkas — the record books of the Jewish community — as well as the symbols of amulets against evil spirits, above all Lilith and Agrat bat Mahallat. The concise language of the signs conveyed the caste and clan affiliation of the deceased. Thus, ancient musical instruments or a jug were depicted on the grave of a Levite, a descendant of the Levi family, and a flock without a shepherd on the grave of a rabbi.

Hands over burning candles or only candles in Sabbath candlesticks were depicted over the graves of women, as lighting fires during domestic rites was their sacred duty. An open book may have been placed on the grave of an author of religious writings. A goose feather, alone or held in the hand, was on the grave of a scribe of sacred texts, scissors indicated a tailor’s grave, a chain or other jewelery — a jeweler’s one.

Death also had its own symbolism, marked by a broken vessel or boat, a broken candle, an overturned extinguished lamp, a fallen crown, or a broken branch. The epitaph, thanks to its emotionally expressive Hebrew lettering, was often the main decorative element of a tombstone.