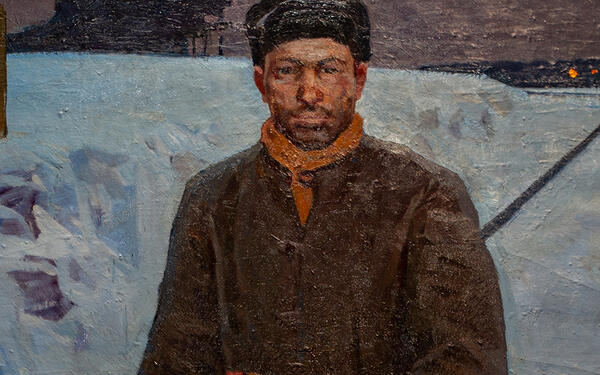

The painting ‘Trackman’ was created by Igor Simonov in 1962. He witnessed the last years of the profession: by the end of the 1960s, trackmen were replaced by track servicemen. However, in the early 1960s, it was still impossible to imagine train traffic without trackmen: their responsibilities included monitoring the condition of railroads and ensuring their safety.

Every trackman was in charge of a section, which was 7–8 kilometers long, and had to oversee every railroad tie in it. They needed to notice even the slightest out-of-the-ordinary curve in a rail track or a loose screw, and then report it to a repairman to be fixed. If a defect was too serious to be fixed on the spot (like a broken rail), a trackman would stop the next approaching train and call for a maintenance team. No matter what it was like outside — freezing or hot, pouring rain or snow — a trackman was always supposed to be ready to avert a potential disaster.

Igor Simonov started using scenes with bold workers in the early 1950s when he was studying at the Repin Academic Institute of Fine Arts in Leningrad. This interest in the working class can be attributed to the fact that during the war Simonov mastered a profession of a miller at the Uralmash plant, where he had the opportunity to experience all the hardship of manual labor for himself.

In the 1960s, the Soviet authorities began to duly appreciate Simonov’s artwork, for he created austere style paintings dedicated to shock workers, that were widely exhibited in the country and even beyond. The museum collection houses his other important canvases, glorifying heroic acts of working-class members, such as “Foundry Workers” created in 1959 and the 1964 “My Heroes”.

However, “Trackman” stands out from all other Simonov’s paintings. In contrast with epic paintings, which have no complex subject matter and simply outline the toughness of enthusiastic workers, this painting rather shows an ordinary slightly tired man.

Simonov made the trackman a central element of the canvas, reducing the composition to a massive figure enhanced by the background of snowy wilderness. He simplified the outlines and forms and chose to avoid stiff poses and dramatic gestures. The absence of excessive detailing enables the viewers to focus on the trackman’s face and see past his readiness and high spirits to reveal his resignation and determination to continue with his tough task. By creating this truthful image, the artist made a slight break from the tradition of Socialist Realism.

Every trackman was in charge of a section, which was 7–8 kilometers long, and had to oversee every railroad tie in it. They needed to notice even the slightest out-of-the-ordinary curve in a rail track or a loose screw, and then report it to a repairman to be fixed. If a defect was too serious to be fixed on the spot (like a broken rail), a trackman would stop the next approaching train and call for a maintenance team. No matter what it was like outside — freezing or hot, pouring rain or snow — a trackman was always supposed to be ready to avert a potential disaster.

Igor Simonov started using scenes with bold workers in the early 1950s when he was studying at the Repin Academic Institute of Fine Arts in Leningrad. This interest in the working class can be attributed to the fact that during the war Simonov mastered a profession of a miller at the Uralmash plant, where he had the opportunity to experience all the hardship of manual labor for himself.

In the 1960s, the Soviet authorities began to duly appreciate Simonov’s artwork, for he created austere style paintings dedicated to shock workers, that were widely exhibited in the country and even beyond. The museum collection houses his other important canvases, glorifying heroic acts of working-class members, such as “Foundry Workers” created in 1959 and the 1964 “My Heroes”.

However, “Trackman” stands out from all other Simonov’s paintings. In contrast with epic paintings, which have no complex subject matter and simply outline the toughness of enthusiastic workers, this painting rather shows an ordinary slightly tired man.

Simonov made the trackman a central element of the canvas, reducing the composition to a massive figure enhanced by the background of snowy wilderness. He simplified the outlines and forms and chose to avoid stiff poses and dramatic gestures. The absence of excessive detailing enables the viewers to focus on the trackman’s face and see past his readiness and high spirits to reveal his resignation and determination to continue with his tough task. By creating this truthful image, the artist made a slight break from the tradition of Socialist Realism.