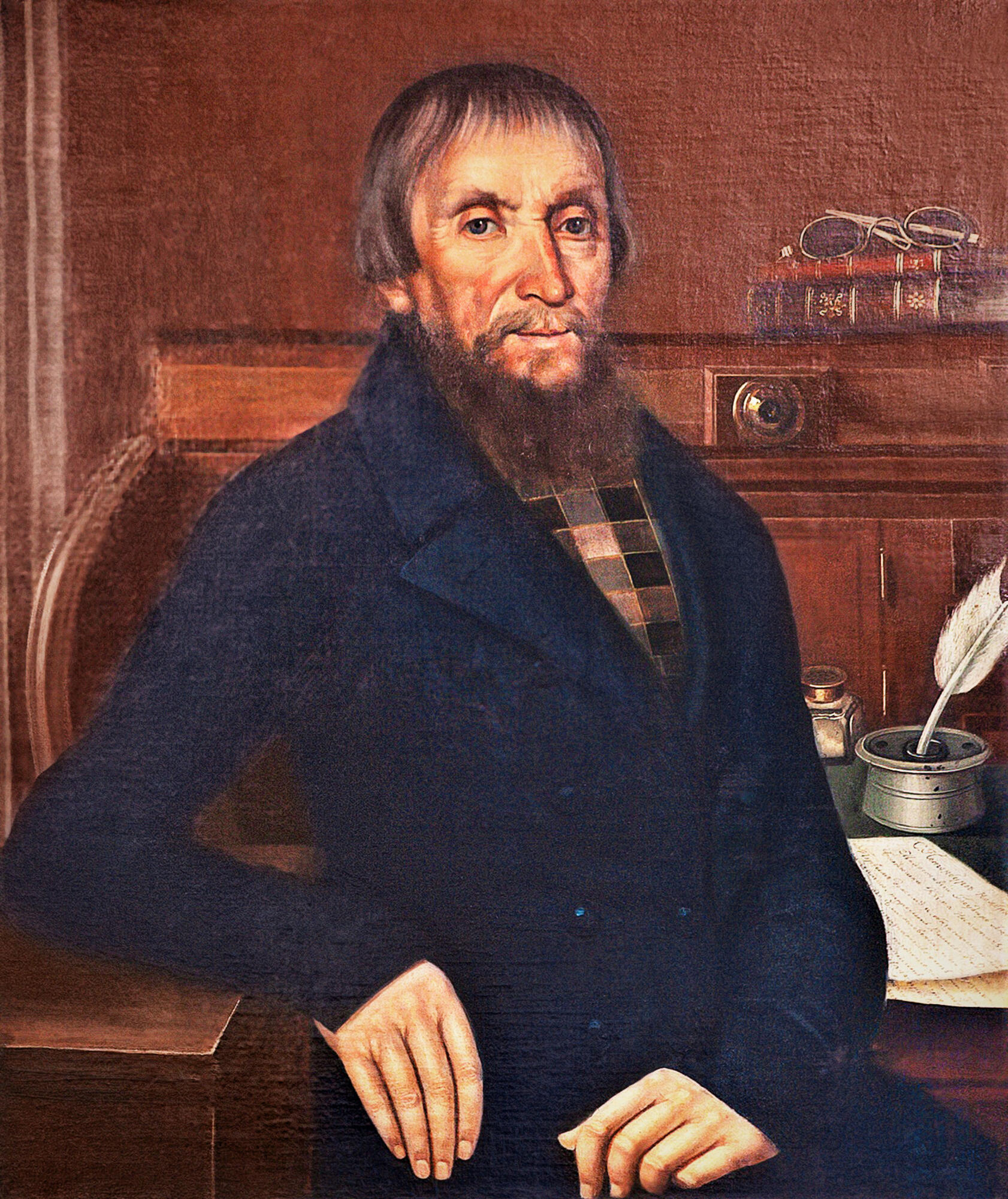

The mid-19th century canvas is a textbook example of a provincial portrait of a merchant. It was created by an unknown artist. Most likely, he did not have an academic education in art: one can see that the merchant’s figure and hands are painted anatomically incorrectly.

Most portraits of this type appeared in the 1790s–1850s; they combine the features of professional and primitive art. At the turn of the 17th century, most provincial painters were self-taught. Art schools appeared in Russian provinces since the 1830s, whereas the Imperial Academy of Arts began to train art teachers only in the middle of the 19th century.

At the same time, provincial merchants commissioned portraits more and more often: at the end of the 18th century, they saw themselves as member of a socio-cultural class which differed from both the nobility and peasants. Therefore, strict canons were established for provincial merchant portraits. Everything was supposed to highlight their social status: the setting, character’s pose, personal belongings and even some features of appearance, for instance, beards.

For a long time, the hero of the portrait from the collection of the Tomsk Regional Art Museum remained unknown. However, museum’s experts determined his identity by the lines in the letter on the desk: “November, St. Petersburg… Dear sir, dear Father Kozma Nikitich! I consider it my first and most important duty to ask for your parental blessing…” In those days, artists often used the “painted word” technique to indicate the identity of the sitter.

Researchers examined archives and found a gallery of portraits depicting Rostov merchants Pleshanovs. Kuzma Nikitich turned out to be the family’s ancestor on the female line — the merchant of the 2nd guild Kuzma Kuznetsov. Merchants of the 2nd guild could own small river vessels, factories and plants, and even hold senior positions in city governments.

Kuzma Kuznetsov lived in Rostov and was engaged in goat down and chIcory trade in St. Petersburg. Rostov merchants traditionally sold their goods all throughout Russia. Kuznetsov enjoyed great authority among other merchants and held various public positions: he was a judge of a verbal commercial court, the city’s mayor (“starosta”) and representative in the magistrate — the city court.

Most portraits of this type appeared in the 1790s–1850s; they combine the features of professional and primitive art. At the turn of the 17th century, most provincial painters were self-taught. Art schools appeared in Russian provinces since the 1830s, whereas the Imperial Academy of Arts began to train art teachers only in the middle of the 19th century.

At the same time, provincial merchants commissioned portraits more and more often: at the end of the 18th century, they saw themselves as member of a socio-cultural class which differed from both the nobility and peasants. Therefore, strict canons were established for provincial merchant portraits. Everything was supposed to highlight their social status: the setting, character’s pose, personal belongings and even some features of appearance, for instance, beards.

For a long time, the hero of the portrait from the collection of the Tomsk Regional Art Museum remained unknown. However, museum’s experts determined his identity by the lines in the letter on the desk: “November, St. Petersburg… Dear sir, dear Father Kozma Nikitich! I consider it my first and most important duty to ask for your parental blessing…” In those days, artists often used the “painted word” technique to indicate the identity of the sitter.

Researchers examined archives and found a gallery of portraits depicting Rostov merchants Pleshanovs. Kuzma Nikitich turned out to be the family’s ancestor on the female line — the merchant of the 2nd guild Kuzma Kuznetsov. Merchants of the 2nd guild could own small river vessels, factories and plants, and even hold senior positions in city governments.

Kuzma Kuznetsov lived in Rostov and was engaged in goat down and chIcory trade in St. Petersburg. Rostov merchants traditionally sold their goods all throughout Russia. Kuznetsov enjoyed great authority among other merchants and held various public positions: he was a judge of a verbal commercial court, the city’s mayor (“starosta”) and representative in the magistrate — the city court.