The Tomsk Art Museum houses several portraits from the family gallery of Rostov merchants Pleshanovs. They were donated to the museum by a descendant of the family, whose name has not been preserved.

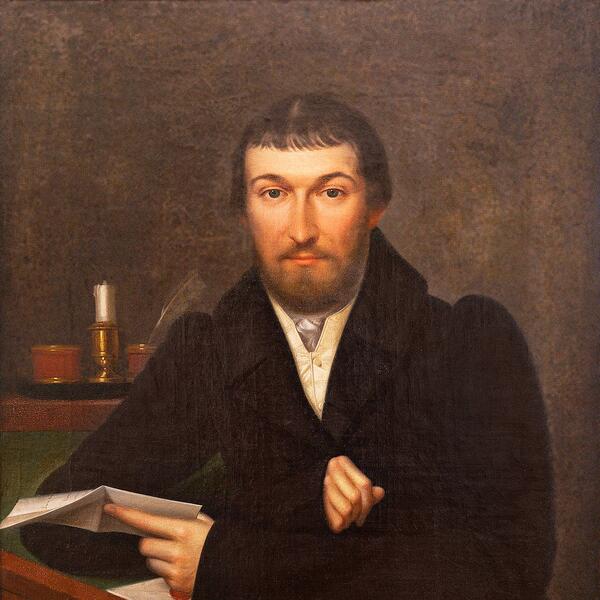

Ivan Pleshanov, the uncle of artist Pavel Pleshanov, ran the family business in Kazan. His portrait is somewhat different from the ‘deductive’ portraits of the older generation.

Compared to the portraits of his father Maxim Pleshanov and father-in-law Kuzma Kuznetsov, which are also displayed in the museum, the portrait of Ivan Pleshanov, dated to the first half of the 19th century, is less old-fashioned. The depiction of the figure in the interior still fully corresponds to the canonical style of an ‘icon-parsuna’, but the face and hands are painted in detail, which was not typical for ceremonial and semi-parade portraits of the previous 18th century.

In the history of Russian painting, parsuna is a portrait that looks more like an icon. It is distinguished by an emphasis on the hands and face, as well as an idealization of the characters. Some artists left ‘hints’ in the parsunas — certain attributes and symbols that helped to determine the identity of the depicted person. Those could be medals, letters with well-readable lines, business cards on the table.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the aesthetic ideals of the merchant class changed. The characteristic hairstyle ‘in a round crop’ and Pleshanov’s beard still demonstrate his loyalty to the traditions of his social class, but the young merchant is depicted in the portrait with a short-trimmed beard. It means that the hero of the painting followed the European trends, which were popular in men’s fashion in the 1830s.

Pleshanov holds a letter in his hands. The surviving copies of letters written by him in his youth indicate that he was a well-read person who loved books. In his letters, he wrote about Diogenes, Seneca and Nero, and Nikolay Karamzin’s fundamental work on national history. Pleshanov was concerned with the problems of preserving spirituality and charitable traditions. He was worried about the morality of his own family, which had gained considerable wealth and continued to increase their capital.

Thus, in one of the letters, Pleshanov, who was sent to work in St. Petersburg as a boy and was forced to part with his small homeland, Rostov, regretted:

Ivan Pleshanov, the uncle of artist Pavel Pleshanov, ran the family business in Kazan. His portrait is somewhat different from the ‘deductive’ portraits of the older generation.

Compared to the portraits of his father Maxim Pleshanov and father-in-law Kuzma Kuznetsov, which are also displayed in the museum, the portrait of Ivan Pleshanov, dated to the first half of the 19th century, is less old-fashioned. The depiction of the figure in the interior still fully corresponds to the canonical style of an ‘icon-parsuna’, but the face and hands are painted in detail, which was not typical for ceremonial and semi-parade portraits of the previous 18th century.

In the history of Russian painting, parsuna is a portrait that looks more like an icon. It is distinguished by an emphasis on the hands and face, as well as an idealization of the characters. Some artists left ‘hints’ in the parsunas — certain attributes and symbols that helped to determine the identity of the depicted person. Those could be medals, letters with well-readable lines, business cards on the table.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the aesthetic ideals of the merchant class changed. The characteristic hairstyle ‘in a round crop’ and Pleshanov’s beard still demonstrate his loyalty to the traditions of his social class, but the young merchant is depicted in the portrait with a short-trimmed beard. It means that the hero of the painting followed the European trends, which were popular in men’s fashion in the 1830s.

Pleshanov holds a letter in his hands. The surviving copies of letters written by him in his youth indicate that he was a well-read person who loved books. In his letters, he wrote about Diogenes, Seneca and Nero, and Nikolay Karamzin’s fundamental work on national history. Pleshanov was concerned with the problems of preserving spirituality and charitable traditions. He was worried about the morality of his own family, which had gained considerable wealth and continued to increase their capital.

Thus, in one of the letters, Pleshanov, who was sent to work in St. Petersburg as a boy and was forced to part with his small homeland, Rostov, regretted: