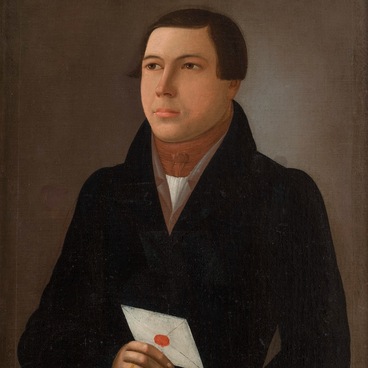

The exhibition presents a portrait of merchant Timofey Suzdaltsev, signed by artist Fedor Semyonov. Today, it is his only work known to art historians. There is no information about Semyonov, but a document of the end of the 18th century mentioning merchants of the 3rd guild with this surname. Perhaps, the author of this portrait was a descendant of one of them.

In the portrait, Semyonov depicted Suzdaltsev as a teenager. The merchant is almost 15 years old here, but his childish features make him look younger. At the same time, Semyonov has given his image the features typical of a merchant’s portrait: Suzdaltsev has a deep and concentrated look, a simple and natural posture. His hair is cut, and he is dressed according to adult fashion. He wears a black fitted jacket with slightly raised shoulders and a collar, white broad-striped shirt with high standing collar, and brown scarf tied around his neck.

Timofey Suzdaltsev was born into one of the most influential and wealthy merchant dynasties of Murom. He was a relative of merchants Vasily and Fedor Suzdaltsev, whose portraits are also housed in the museum’s collection. Timofey Suzdaltsev’s grandfather was the owner of the city’s first linen establishment and shop buildings on Market Square, and was three times elected mayor of Murom.

The genre of a merchant’s portrait emerged in the 18th century at the junction of professional and primitive art. At that time, the merchant class played an important role in the economy and society of Russia. Merchants, their wives and children were often depicted in portraits.

Merchant portraiture was influenced by the parsuna, an early genre of portraiture in the Tsardom of Russia that was close to icon painting. The word “parsuna” was a distorted version of the Latin “persona”, which meant “person, personality”. Later, in the 17th century, a synonymous concept appeared, that is a “portrait”. The original parsuna portrait resemblance was rather conventional: it was possible to determine who was depicted in the picture only by special attributes and inscriptions.

Masters of merchant portraiture, on the contrary, sought to achieve an accurate resemblance to the portrayed. However, as in the parsunas, they depicted the model’s chest-length or waist-length, choosing a three-quarter angle, paying special attention to the face and hands.

In addition, artists sought to emphasize the social status of the portrayed and depicted them in the images of exemplary citizens and family men, model heirs and others.

In the portrait, Semyonov depicted Suzdaltsev as a teenager. The merchant is almost 15 years old here, but his childish features make him look younger. At the same time, Semyonov has given his image the features typical of a merchant’s portrait: Suzdaltsev has a deep and concentrated look, a simple and natural posture. His hair is cut, and he is dressed according to adult fashion. He wears a black fitted jacket with slightly raised shoulders and a collar, white broad-striped shirt with high standing collar, and brown scarf tied around his neck.

Timofey Suzdaltsev was born into one of the most influential and wealthy merchant dynasties of Murom. He was a relative of merchants Vasily and Fedor Suzdaltsev, whose portraits are also housed in the museum’s collection. Timofey Suzdaltsev’s grandfather was the owner of the city’s first linen establishment and shop buildings on Market Square, and was three times elected mayor of Murom.

The genre of a merchant’s portrait emerged in the 18th century at the junction of professional and primitive art. At that time, the merchant class played an important role in the economy and society of Russia. Merchants, their wives and children were often depicted in portraits.

Merchant portraiture was influenced by the parsuna, an early genre of portraiture in the Tsardom of Russia that was close to icon painting. The word “parsuna” was a distorted version of the Latin “persona”, which meant “person, personality”. Later, in the 17th century, a synonymous concept appeared, that is a “portrait”. The original parsuna portrait resemblance was rather conventional: it was possible to determine who was depicted in the picture only by special attributes and inscriptions.

Masters of merchant portraiture, on the contrary, sought to achieve an accurate resemblance to the portrayed. However, as in the parsunas, they depicted the model’s chest-length or waist-length, choosing a three-quarter angle, paying special attention to the face and hands.

In addition, artists sought to emphasize the social status of the portrayed and depicted them in the images of exemplary citizens and family men, model heirs and others.