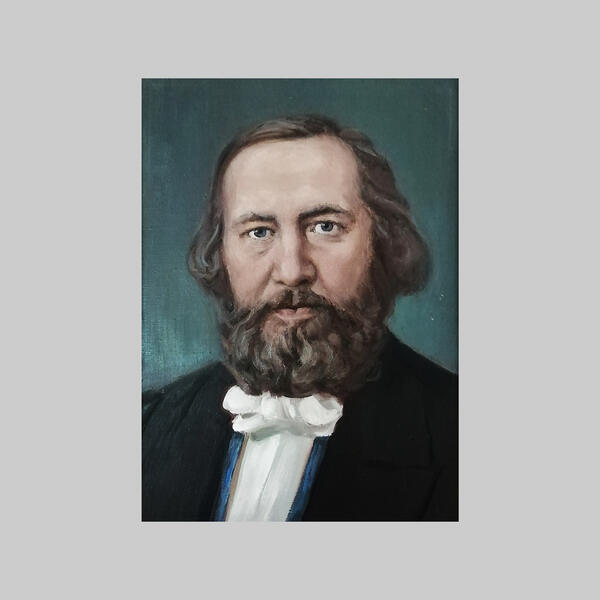

This portrait, made in the late 20th century by the brilliant Ufa painter Anatoly Platonov, depicts Konstantin Sergeevich Aksakov, a Russian literary and public figure, historian, linguist, one of the leaders of the Slavophilic movement, and the writer Sergey Timofeevich Aksakov’s eldest son.

While working on this painting, Platonov used as reference a photo portrait made in Berger’s photo studio in Moscow. In 1851, The Saxon national Carl August Bergner opened a daguerreotype venue in Moscow, but only took up photography two years later. Over the span of 10 years, he took many photographs of major figures of Russian culture, including the returning from exile Decembrists Gavriil Batenkov and Matvey Muravyov-Apostol. The images on Bergner’s photo cards appeared almost three-dimensional due to a special lacquer coating.

Undoubtedly, Platonov also succeeded in imitating depth: despite his soft features, calm and clever look of light gray eyes, Konstantin Sergeevich in his portrait looks like a man of independent mind and strong character. His face is framed with a thick beard, preferred by nearly every Slavophile. At the same time, Konstantin’s clothes follow the high society canons of the 19th century: he wears a snow-white shirt with a bow tie and a dark frock coat.

Konstantin Aksakov was born in 1817. At the age of 15 he became a student of the Faculty of History and Philology of Moscow State University. Two years after his graduation, he got acquainted with a group of Slavophiles, which included the poet and artist Alexei Khomyakov, Russian religious philosopher Ivan Kireevsky, and publicist and philosopher Yuri Samarin. In 1846, his research ‘Lomonosov in the History of Russian Literature and Language’ was published, which brought him a master’s degree in Russian literature. He has written 12 articles for the “Kolokol” magazine, and has also collaborated with the trade-oriented bourgeois magazine “Moskvityanin” and the patriotic magazine “Russian Conversation”.

The most important feature of Konstantin Aksakov’s mentality was his passionate commitment to Slavophilia – a literary, religious and philosophical movement, supporters of which believed that Russia had substantial differences from Western countries. He believed that the true values of the Russian people were in the spiritual and religious sphere. As an ardent opponent of revolutionary movements, he advocated the early abolition of serfdom.

As the majority of Slavophiles, Konstantin Aksakov idealized the image of simple Russian people and believed that all people should live by simple peasant customs. That’s why he often wore a simple shirt and a kalpak – a high-crowned cap usually made of felt. He treated his dress very carefully; for him, it was a symbol of humility and piety. He would often say: “A tailcoat can be a revolutionist, but a zipun could never be one.” Zipun is a kind of peasant robe without collar, made of rough homemade cloth.

While working on this painting, Platonov used as reference a photo portrait made in Berger’s photo studio in Moscow. In 1851, The Saxon national Carl August Bergner opened a daguerreotype venue in Moscow, but only took up photography two years later. Over the span of 10 years, he took many photographs of major figures of Russian culture, including the returning from exile Decembrists Gavriil Batenkov and Matvey Muravyov-Apostol. The images on Bergner’s photo cards appeared almost three-dimensional due to a special lacquer coating.

Undoubtedly, Platonov also succeeded in imitating depth: despite his soft features, calm and clever look of light gray eyes, Konstantin Sergeevich in his portrait looks like a man of independent mind and strong character. His face is framed with a thick beard, preferred by nearly every Slavophile. At the same time, Konstantin’s clothes follow the high society canons of the 19th century: he wears a snow-white shirt with a bow tie and a dark frock coat.

Konstantin Aksakov was born in 1817. At the age of 15 he became a student of the Faculty of History and Philology of Moscow State University. Two years after his graduation, he got acquainted with a group of Slavophiles, which included the poet and artist Alexei Khomyakov, Russian religious philosopher Ivan Kireevsky, and publicist and philosopher Yuri Samarin. In 1846, his research ‘Lomonosov in the History of Russian Literature and Language’ was published, which brought him a master’s degree in Russian literature. He has written 12 articles for the “Kolokol” magazine, and has also collaborated with the trade-oriented bourgeois magazine “Moskvityanin” and the patriotic magazine “Russian Conversation”.

The most important feature of Konstantin Aksakov’s mentality was his passionate commitment to Slavophilia – a literary, religious and philosophical movement, supporters of which believed that Russia had substantial differences from Western countries. He believed that the true values of the Russian people were in the spiritual and religious sphere. As an ardent opponent of revolutionary movements, he advocated the early abolition of serfdom.

As the majority of Slavophiles, Konstantin Aksakov idealized the image of simple Russian people and believed that all people should live by simple peasant customs. That’s why he often wore a simple shirt and a kalpak – a high-crowned cap usually made of felt. He treated his dress very carefully; for him, it was a symbol of humility and piety. He would often say: “A tailcoat can be a revolutionist, but a zipun could never be one.” Zipun is a kind of peasant robe without collar, made of rough homemade cloth.