‘Portrait of an Italian woman’ is the work of Ksenia Alekseeva, granddaughter of the poet Yevgeniy Boratynskiy. She went down in history as a teacher, artist and the author of memoirs. In 1896, Ksenia enrolled in the Kazan Art School and four years later passed the examination for the title of governess.

Alekseeva was passionate about teaching and the notion of public education. In 1902, she organized a boarding school for peasant children in the Shushary estate of the Boratynskiy family, where teaching was combined with handicrafts, outings, figurative arts and theatre.

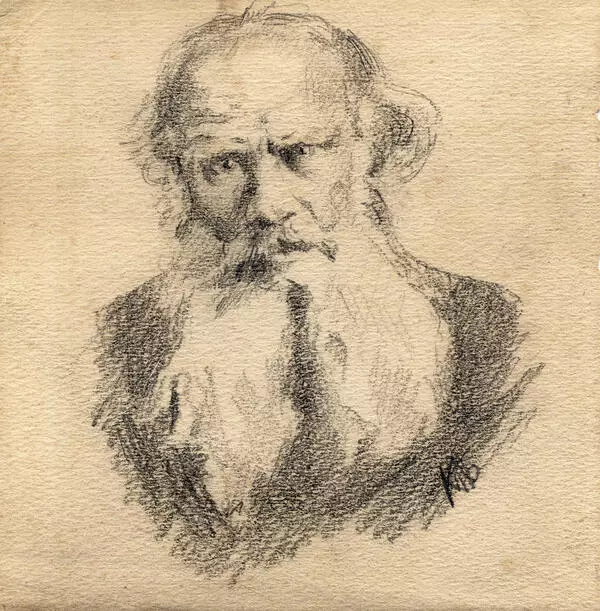

Five years later, Ksenia made a trip to Yasnaya Polana to Leo Tolstoy to herself familiar with his pedagogical ideas. In the same year, she married the peasant of the Kazan governorate Arkhip Alekseev, who subsequently received a higher education and began to teach history himself. Three children were born in this marriage.

After the revolutionary events of 1917, Alekseeva worked in various institutions of public education. She accepted the revolution and would often say: ‘I can’t help but be grateful to the Bolsheviks for taking the heaviest burden off my shoulders: wealth. To be freed from any property, from any money, was wonderful! ’ In her last years she lived in Moscow and became the keeper of the Boratynskiy family collection.

This portrait was done in Rome in 1900 during a journey through Europe that Ksenia undertook with mother Olga Boratynskaya and sister Ekaterina. In her memoirs, she describes an episode related to the portrait of an Italian woman: “As soon as we arrived in Rome, I entered the art studio to use the time. Now we”re in the studio painting a portrait of an Italian woman in a national costume. I want to present all these studies at the Art School, and my maestro went and re-painted the cheek, and I scraped it off and re-did it my way. And when I left, he suddenly said to me: “Stay in Rome, continue working in the studio, and I promise you that in a year you will exhibit your paintings - you have talent!"”

Alekseeva was passionate about teaching and the notion of public education. In 1902, she organized a boarding school for peasant children in the Shushary estate of the Boratynskiy family, where teaching was combined with handicrafts, outings, figurative arts and theatre.

Five years later, Ksenia made a trip to Yasnaya Polana to Leo Tolstoy to herself familiar with his pedagogical ideas. In the same year, she married the peasant of the Kazan governorate Arkhip Alekseev, who subsequently received a higher education and began to teach history himself. Three children were born in this marriage.

After the revolutionary events of 1917, Alekseeva worked in various institutions of public education. She accepted the revolution and would often say: ‘I can’t help but be grateful to the Bolsheviks for taking the heaviest burden off my shoulders: wealth. To be freed from any property, from any money, was wonderful! ’ In her last years she lived in Moscow and became the keeper of the Boratynskiy family collection.

This portrait was done in Rome in 1900 during a journey through Europe that Ksenia undertook with mother Olga Boratynskaya and sister Ekaterina. In her memoirs, she describes an episode related to the portrait of an Italian woman: “As soon as we arrived in Rome, I entered the art studio to use the time. Now we”re in the studio painting a portrait of an Italian woman in a national costume. I want to present all these studies at the Art School, and my maestro went and re-painted the cheek, and I scraped it off and re-did it my way. And when I left, he suddenly said to me: “Stay in Rome, continue working in the studio, and I promise you that in a year you will exhibit your paintings - you have talent!"”