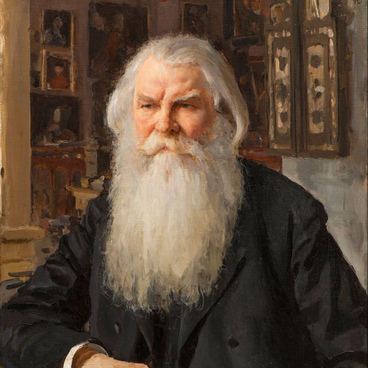

The portrait of Empress Catherine II, displayed in the State Historical Museum collection, is a rare replica of a painting created by court artist Stefano Torelli. Prior to the revolution, the original was kept in Russia; presently, however, it is housed in a private collection abroad.

In the portrait, Catherine the Great is depicted in a dress that resembles the traditional Russian costume of the 17th — 18th century. It is likely that it was Catherine’s masquerade outfit, as the artist painted her with a black carnival mask in her hands. She also wears a headdress similar to the traditional Russian kokoshnik. It is embroidered with pearls and precious stones.

The royal court’s attitude towards the Russian style was then very different from that in the 17th century. At the time of Tsar Alexis I the Quietest, only national clothes were acceptable for courtiers for everyday wear: just tsareviches (sons of a tsar) and their immediate entourage were allowed to dress in Western fashion. At the same time, European costumes were often worn at masquerades.

When Peter I ascended the throne, many traditions were drastically changed. The decree of the new monarch forbade aristocrats to wear Russian style dresses and instructed “the female sex of all estates to wear a dress, hats, kuntysh [kaftan], bostrogs under them [short jacket], skirts, and German shoes, and the Russian dresses, <…> should not be worn from here onward.” Thus, sarafans (sundresses) and kokoshniks became part of masquerade attire. Students in the 18th century were forced to wear “peasant” (that is, national) clothes as punishment for misconduct.

Under Elizabeth Petrovna, a “tyranny of fashion” began in the aristocratic society of Saint Petersburg. By special decrees, the empress required all court ladies to wear French Baroque dresses and change clothes several times a day: for breakfast and morning reception of guests, for daytime affairs and an evening outing. When Elizabeth Petrovna hosted receptions in country palaces, the guests’ clothes had to be in harmony with the color and the interiors. The changes also affected masquerade costumes: during her reign, ladies were required to wear men’s outfits, and gentlemen — women’s ones. Catherine II recalled in her notes: “… a man’s clothing suited the empress only. With her tall stature and some heftiness, she looked wonderful in a man’s outfit.”

When Catherine herself came to power, the Russian style fashion was again popular at the court. The court ladies did not comply with strict requirements for the costume: they were allowed to wear both European dresses and outfits with national elements — for example, long hanging sleeves and a short train. This type of dresses was sometimes called “a sarafan a la Française”.

In the portrait, Catherine the Great is depicted in a dress that resembles the traditional Russian costume of the 17th — 18th century. It is likely that it was Catherine’s masquerade outfit, as the artist painted her with a black carnival mask in her hands. She also wears a headdress similar to the traditional Russian kokoshnik. It is embroidered with pearls and precious stones.

The royal court’s attitude towards the Russian style was then very different from that in the 17th century. At the time of Tsar Alexis I the Quietest, only national clothes were acceptable for courtiers for everyday wear: just tsareviches (sons of a tsar) and their immediate entourage were allowed to dress in Western fashion. At the same time, European costumes were often worn at masquerades.

When Peter I ascended the throne, many traditions were drastically changed. The decree of the new monarch forbade aristocrats to wear Russian style dresses and instructed “the female sex of all estates to wear a dress, hats, kuntysh [kaftan], bostrogs under them [short jacket], skirts, and German shoes, and the Russian dresses, <…> should not be worn from here onward.” Thus, sarafans (sundresses) and kokoshniks became part of masquerade attire. Students in the 18th century were forced to wear “peasant” (that is, national) clothes as punishment for misconduct.

Under Elizabeth Petrovna, a “tyranny of fashion” began in the aristocratic society of Saint Petersburg. By special decrees, the empress required all court ladies to wear French Baroque dresses and change clothes several times a day: for breakfast and morning reception of guests, for daytime affairs and an evening outing. When Elizabeth Petrovna hosted receptions in country palaces, the guests’ clothes had to be in harmony with the color and the interiors. The changes also affected masquerade costumes: during her reign, ladies were required to wear men’s outfits, and gentlemen — women’s ones. Catherine II recalled in her notes: “… a man’s clothing suited the empress only. With her tall stature and some heftiness, she looked wonderful in a man’s outfit.”

When Catherine herself came to power, the Russian style fashion was again popular at the court. The court ladies did not comply with strict requirements for the costume: they were allowed to wear both European dresses and outfits with national elements — for example, long hanging sleeves and a short train. This type of dresses was sometimes called “a sarafan a la Française”.