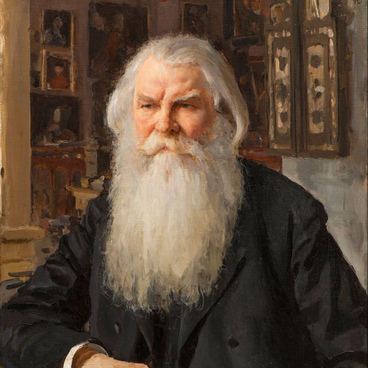

The State Historical Museum houses a portrait of the conqueror of Siberia, Cossack ataman Yermak Timofeyevich. An unknown artist created this oil painting on a tin sheet in the late 18th — early 19th century. This depiction does not reflect the true appearance of the ataman: it is a general image popular with artists of that time. There are no lifetime images of Yermak: in the 16th century, when he lived, the secular portrait genre had not yet been developed in Russia, artists created mainly icons and illustrations for religious books.

Yermak’s personality is surrounded by legends. The Urals, the Don, the Russian North are mentioned as possible places of his birth. According to one hypothesis, Yermak was of Turkic origin. A description of the ataman’s appearance is given in one of the Siberian chronicles, compiled almost a century after his death: “he was courageous, and humane, and a man of stature, full of wisdom, flat-faced, dark-bearded, of average height, sturdy, and broad-shouldered.”

This portrait of Yermak reflects the romantic ideas of that time about the legendary historical hero. It belongs to a particular type of historical genre, when an artist creates a fictional portrait of a person based on their own ideas about the life and character of the said person. A number of such “depictions” of Yermak — paintings and engravings — are known. They were very popular with peasants. The earliest works belong to the late 17th — early 18th century. As a rule, such portraits show an elderly man with large masculine features and a black beard, wearing semi-fantastic military armor, not characteristic of the Cossacks. Such portraits might have one common prototype.

In 1582, Yermak and a small Cossack druzhina (small army) were recruited by the Stroganov merchant family, who were engaged in extracting salt in the Urals. Yermak protected their territories from Tatar raids. Later, the ataman led his Cossacks on a campaign beyond the Ural Mountains, to the lands of the Siberian Khan Kuchum, on a mission to finally defeat him. The druzhina consisted of a little more than 800 people, and Kuchum’s troops outnumbered it many times. But the Tatars were poorly armed, so the Cossacks managed to snatch several major victories and take the Siberian Khan’s stavka (the capital) — the city of Qashliq. Some local indigenous peoples swore allegiance to the Russians, Yermak imposed yasak (fur tribute) on them, and in 1583 informed Ivan the Terrible about his conquest of Siberia.

According to a legend, the tsar rewarded the ataman with two sets of chain mail, which Yermak constantly wore, one under the other. It is believed that they caused his death. In 1585, the Tatars attacked a Cossack squad, Yermak was seriously wounded and could not swim across the Irtysh River to get to his ship: his heavy armor pulled him to the bottom.

Yermak’s personality is surrounded by legends. The Urals, the Don, the Russian North are mentioned as possible places of his birth. According to one hypothesis, Yermak was of Turkic origin. A description of the ataman’s appearance is given in one of the Siberian chronicles, compiled almost a century after his death: “he was courageous, and humane, and a man of stature, full of wisdom, flat-faced, dark-bearded, of average height, sturdy, and broad-shouldered.”

This portrait of Yermak reflects the romantic ideas of that time about the legendary historical hero. It belongs to a particular type of historical genre, when an artist creates a fictional portrait of a person based on their own ideas about the life and character of the said person. A number of such “depictions” of Yermak — paintings and engravings — are known. They were very popular with peasants. The earliest works belong to the late 17th — early 18th century. As a rule, such portraits show an elderly man with large masculine features and a black beard, wearing semi-fantastic military armor, not characteristic of the Cossacks. Such portraits might have one common prototype.

In 1582, Yermak and a small Cossack druzhina (small army) were recruited by the Stroganov merchant family, who were engaged in extracting salt in the Urals. Yermak protected their territories from Tatar raids. Later, the ataman led his Cossacks on a campaign beyond the Ural Mountains, to the lands of the Siberian Khan Kuchum, on a mission to finally defeat him. The druzhina consisted of a little more than 800 people, and Kuchum’s troops outnumbered it many times. But the Tatars were poorly armed, so the Cossacks managed to snatch several major victories and take the Siberian Khan’s stavka (the capital) — the city of Qashliq. Some local indigenous peoples swore allegiance to the Russians, Yermak imposed yasak (fur tribute) on them, and in 1583 informed Ivan the Terrible about his conquest of Siberia.

According to a legend, the tsar rewarded the ataman with two sets of chain mail, which Yermak constantly wore, one under the other. It is believed that they caused his death. In 1585, the Tatars attacked a Cossack squad, Yermak was seriously wounded and could not swim across the Irtysh River to get to his ship: his heavy armor pulled him to the bottom.