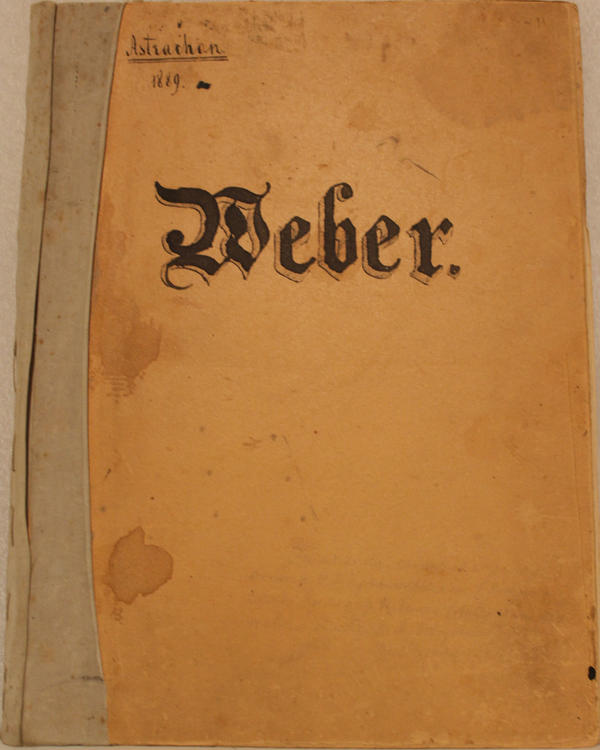

The cardboard binder bearing an inscription Weber is a writing pad of yellow cardboard with five glued-in sheets of thinner paper. On the cover there are calligraphic inscriptions Weber and Astrachan 1889 by Konstantin Fyodorov and an explanatory inscription by Mikhail Chernyshevsky.

A multivolume edition of ‘The General History’ by Georg Weber is the largest translation work by Nikolay Chernyshevsky; he started the translation in 1885. Chernyshevsky independently selected the author for the translation. He advised his client that his plan was to complete the work within three years. In March 1885 Chernyshevsky sent out the first 76 pages of the translation, and in September he advised his son Mikhail that he had sent to the publisher the completed translation of the first volume. A total of 12 volumes out of 14 had been published by 1889 under the pen-name of Andreyev.

In late 1885 there started to appear complimentary reviews on the translation of the first volume of ‘The General History’. To expedite the work, Chernyshevsky engaged an assistant: Konstantin Fyodorov. The translation work started to move faster: for about a year Chernyshevsky translated four volumes.

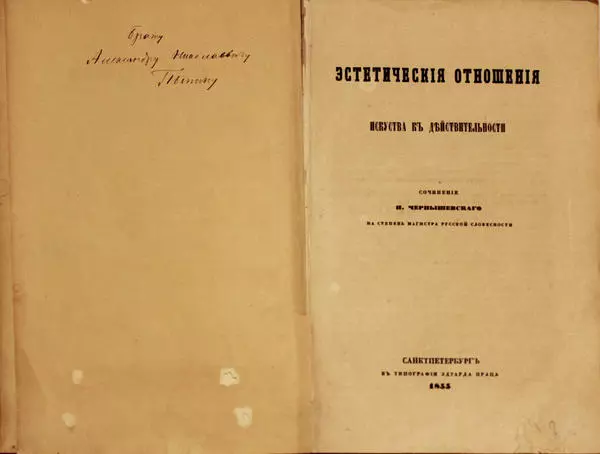

Moreover, he did not just translate the work by Weber, but also tried to ‘clean’ it. With the advancement of the work, his dissatisfaction with the German original was building up. In June 1887 Chernyshevsky noted that ‘Weber has a lot of twaddle’ and also ‘a lot of gaps that need to be filled’. He wrote his introductions to some of the articles combining them under the general title of ‘An Essay on Scientific Concepts on Some Issues of General History’: ‘On Races’, ‘On Classifying People by Their Language’ and ‘On Difference between People Based on Their National Character’, etc.

Additions introduced by Chernyshevsky into the text by Weber materially modified the philosophy of the German historian. For example, the author tended to explain certain historical events by people ethnicity. In his article introduced into the seventh volume, Chernyshevsky explained that no single race has, or should have, privileges over others.

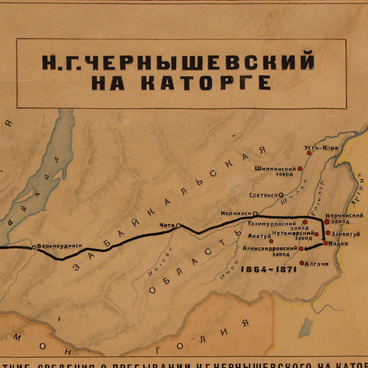

Chernyshevsky’s view on history is based on the principle that he outlined in one of his letters from Siberia to his sons:

A multivolume edition of ‘The General History’ by Georg Weber is the largest translation work by Nikolay Chernyshevsky; he started the translation in 1885. Chernyshevsky independently selected the author for the translation. He advised his client that his plan was to complete the work within three years. In March 1885 Chernyshevsky sent out the first 76 pages of the translation, and in September he advised his son Mikhail that he had sent to the publisher the completed translation of the first volume. A total of 12 volumes out of 14 had been published by 1889 under the pen-name of Andreyev.

In late 1885 there started to appear complimentary reviews on the translation of the first volume of ‘The General History’. To expedite the work, Chernyshevsky engaged an assistant: Konstantin Fyodorov. The translation work started to move faster: for about a year Chernyshevsky translated four volumes.

Moreover, he did not just translate the work by Weber, but also tried to ‘clean’ it. With the advancement of the work, his dissatisfaction with the German original was building up. In June 1887 Chernyshevsky noted that ‘Weber has a lot of twaddle’ and also ‘a lot of gaps that need to be filled’. He wrote his introductions to some of the articles combining them under the general title of ‘An Essay on Scientific Concepts on Some Issues of General History’: ‘On Races’, ‘On Classifying People by Their Language’ and ‘On Difference between People Based on Their National Character’, etc.

Additions introduced by Chernyshevsky into the text by Weber materially modified the philosophy of the German historian. For example, the author tended to explain certain historical events by people ethnicity. In his article introduced into the seventh volume, Chernyshevsky explained that no single race has, or should have, privileges over others.

Chernyshevsky’s view on history is based on the principle that he outlined in one of his letters from Siberia to his sons: