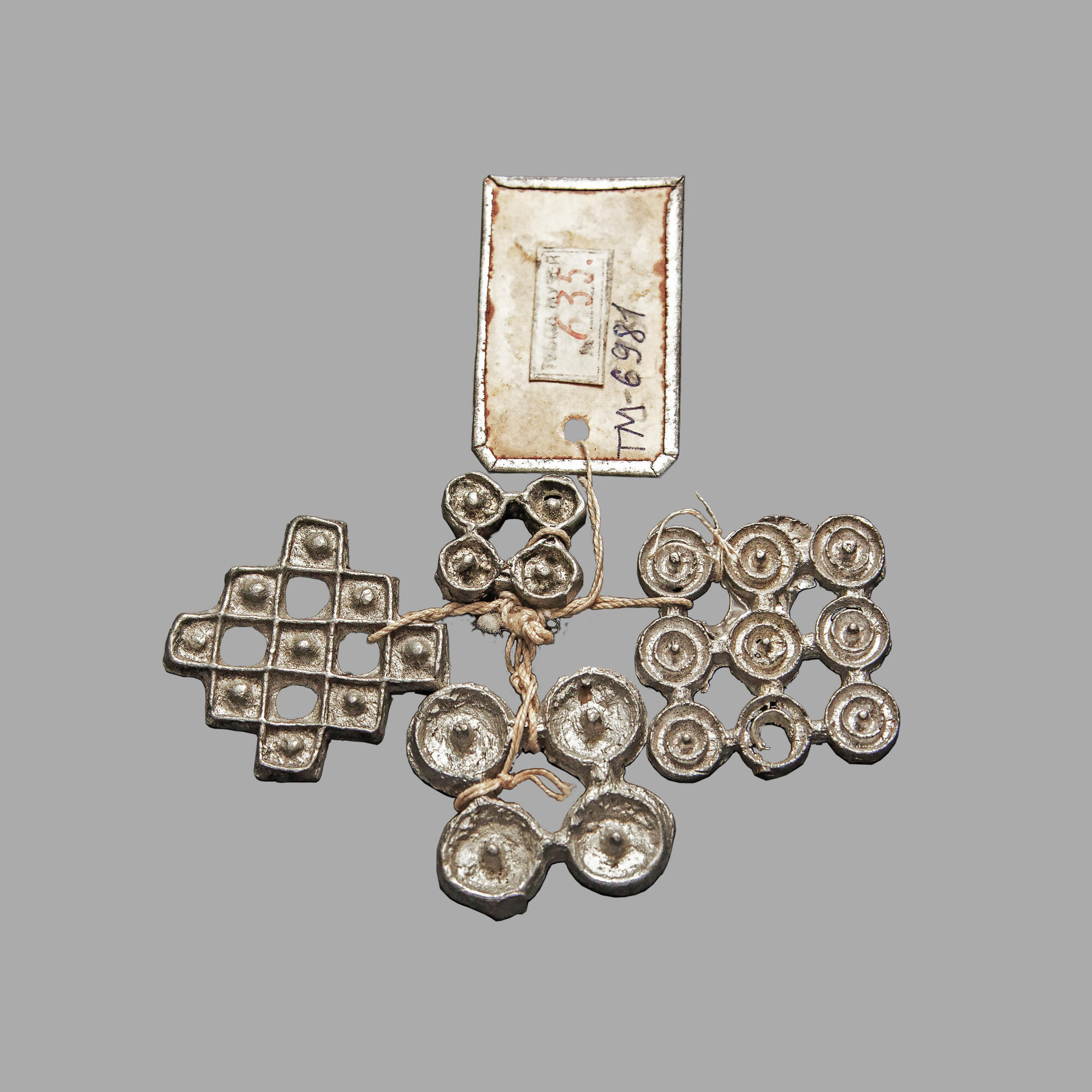

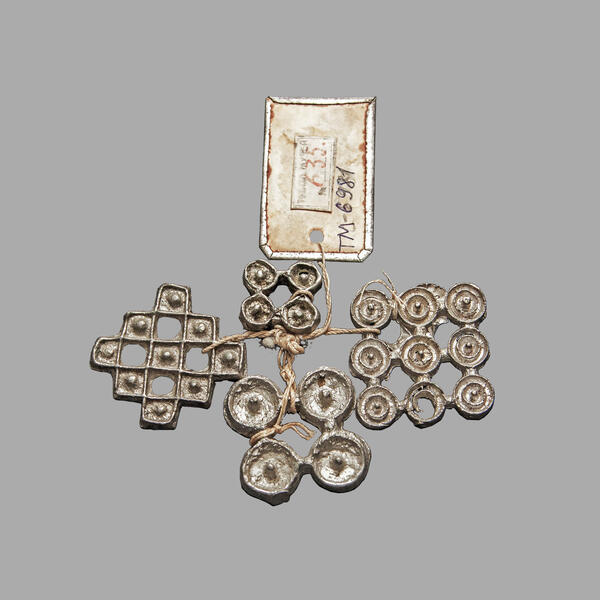

The tin castings were transferred to the Tobolsk Provincial Museum in 1911 from the Organizing Bureau of the Tobolsk Provincial Committee of the First West Siberian Exhibition where they were presented. The castings were sent to the museum’s collection along with the molds for their production.

Ob Ugrians decorated their clothes and the clothes of their patron spirits with such castings. Women sewed them on their own and children’s clothes and used them for decorating belts. Tin was a fairly cheap metal and was popular even when it was replaced by copper and bronze in Western Russia. The four tin castings from the museum’s collection have different ornaments and sizes. Such tin castings were often sewn on the collars of outerwear by the Surgut Khanty.

At the end of the 18th - first half of the 19th centuries, castings were made taking into account ancient traditions. Items made of lead and tin and used in the rites of the Northern groups of Mansi and Khanty can be divided into the following groups, namely: images of patron spirits and their assistants, figures of “ytterma”, i.e. temporary receptacle of the soul of the deceased, shamanic attributes, as well as images of animals, birds, and fish cast for magical purposes.

There were similar castings in the Uryevskiye Yurty of the Lokosovskaya Council of the Surgut District of the Tobolsk province. Small ingots of lead and tin were bought by the Khanty and Mansi from the Russians. In the 20th century, shot was sometimes used for casting ritual accessories. The technological process of casting was extremely simple. Lead or tin ingots were heated in a metal mug on a fire and poured into the prepared form. The mold was cut with a knife from a piece of wood or clay and used once.

Tin castings have storage characteristics related to their physical properties. Natural tin exists in two versions, i.e. white tin and gray tin, which is a material with a lower density compared to the white tin. When cooling, white tin turns to gray, after which the specific volume of the material increases sharply by a quarter, and the metal crumbles into a gray powder. This transformation occurs most quickly at a temperature of -33 °C, and if there is contact between white tin and gray tin, then the so-called “tin plague” quickly spreads from one item to another. Therefore, tin jewelry was kept warm. The tin affected by the “plague” could be melted down and reused.

Ob Ugrians decorated their clothes and the clothes of their patron spirits with such castings. Women sewed them on their own and children’s clothes and used them for decorating belts. Tin was a fairly cheap metal and was popular even when it was replaced by copper and bronze in Western Russia. The four tin castings from the museum’s collection have different ornaments and sizes. Such tin castings were often sewn on the collars of outerwear by the Surgut Khanty.

At the end of the 18th - first half of the 19th centuries, castings were made taking into account ancient traditions. Items made of lead and tin and used in the rites of the Northern groups of Mansi and Khanty can be divided into the following groups, namely: images of patron spirits and their assistants, figures of “ytterma”, i.e. temporary receptacle of the soul of the deceased, shamanic attributes, as well as images of animals, birds, and fish cast for magical purposes.

There were similar castings in the Uryevskiye Yurty of the Lokosovskaya Council of the Surgut District of the Tobolsk province. Small ingots of lead and tin were bought by the Khanty and Mansi from the Russians. In the 20th century, shot was sometimes used for casting ritual accessories. The technological process of casting was extremely simple. Lead or tin ingots were heated in a metal mug on a fire and poured into the prepared form. The mold was cut with a knife from a piece of wood or clay and used once.

Tin castings have storage characteristics related to their physical properties. Natural tin exists in two versions, i.e. white tin and gray tin, which is a material with a lower density compared to the white tin. When cooling, white tin turns to gray, after which the specific volume of the material increases sharply by a quarter, and the metal crumbles into a gray powder. This transformation occurs most quickly at a temperature of -33 °C, and if there is contact between white tin and gray tin, then the so-called “tin plague” quickly spreads from one item to another. Therefore, tin jewelry was kept warm. The tin affected by the “plague” could be melted down and reused.