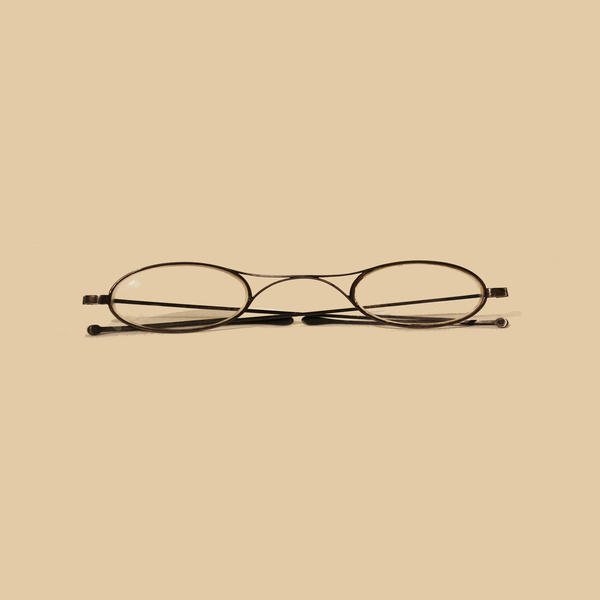

The pride of the exhibits of the Memorial Estate is held by N.G. Chernyshevsky’s spectacles of the period of 1880s. It is exactly these spectacles that can be seen in photographs by Stanislava Klimashevskaya taken in Astrakhan in 1883 and 1888.

N.G. Chernyshevsky’s appearance was influenced by his habits, tastes and ideological convictions. After his exile in Siberia, Chernyshevsky grew long hair and a beard: alongside with his modest suit, simple peak cap and cheap spectacles they made him look like an aged Russian workman.

N.G. Chernyshevsky’s everyday unpretentiousness was caused by his oddness that grew even stronger after his Siberian tribulations. The writer did not care for expensive things and demonstrated utter disregard thereof. To some extent, that resulted from absence of steady income up until March 1885. At that time, Chernyshevsky started the largest work of the last years of his life: translation into Russian of the 15-volume General History by Georg Weber.

Also in Astrakhan Chernyshevsky wrote his Notes While Reading Nekrasov, personal memoirs of his acquaintance with N.A. Dobrolubov, autobiographic excerpts Grandmother’s Stories and Our Happiness. His contemporaries were amazed with Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s industriousness that he retained after the penal servitude and exile in Vilyuisk: at the age of 60, having weak health, he worked “at least 14 hours a day”. Olga Sokratrovna tried to keep strict watch of her husband’s daily routine and did not allow him to work by night.

In addition, Chernyshevsky retained his love of books. In Astrakhan, he joined a library and started using books of its collection. Moreover, when Chernyshevsky lived in his last apartment in Astrakhan, in the house of Stepan Karamyshev, he always had books from the landlord’s extensive library close at hand.

N.G. Chernyshevsky’s appearance was influenced by his habits, tastes and ideological convictions. After his exile in Siberia, Chernyshevsky grew long hair and a beard: alongside with his modest suit, simple peak cap and cheap spectacles they made him look like an aged Russian workman.

N.G. Chernyshevsky’s everyday unpretentiousness was caused by his oddness that grew even stronger after his Siberian tribulations. The writer did not care for expensive things and demonstrated utter disregard thereof. To some extent, that resulted from absence of steady income up until March 1885. At that time, Chernyshevsky started the largest work of the last years of his life: translation into Russian of the 15-volume General History by Georg Weber.

Also in Astrakhan Chernyshevsky wrote his Notes While Reading Nekrasov, personal memoirs of his acquaintance with N.A. Dobrolubov, autobiographic excerpts Grandmother’s Stories and Our Happiness. His contemporaries were amazed with Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s industriousness that he retained after the penal servitude and exile in Vilyuisk: at the age of 60, having weak health, he worked “at least 14 hours a day”. Olga Sokratrovna tried to keep strict watch of her husband’s daily routine and did not allow him to work by night.

In addition, Chernyshevsky retained his love of books. In Astrakhan, he joined a library and started using books of its collection. Moreover, when Chernyshevsky lived in his last apartment in Astrakhan, in the house of Stepan Karamyshev, he always had books from the landlord’s extensive library close at hand.

In this context, Chernyshevsky hardly needed his spectacles for reading: the writer was short sighted, and he could clearly see texts in books and magazines. Most probably, he needed spectacles for household needs and when communicating with people: in the Astrakhan exile, the Chernyshevskys family were visited by their close relatives, as well as by progressive journalists, publishers, newspaper editors, scientists.