When people refer to the Novgorod Nativity Church of the 14th century they clarify — the one “on the Red field” or “in the Cemetery”.

The archaeologist and ethnographer Ruf Gavrilovich Ignatiev, based on the hagiography of the venerable Alfanov brothers (the late 14th — early 15th century), believes that the Nativity Monastery was founded in the 12th century. The archaeologist Ivan Kupriyanovich Kupriyanov, however, considers their 17th-century hagiography historically unreliable.

The Novgorod First Chronicle reports the exact year when, most likely, a wooden church was constructed (1226), but does not mention the monastery.

In the 13th century, the church is referenced to in connection with potter’s fields (common graves; 1230) constructed there and the conflict of the Novgorodians with Alexander, the father of the exiled Prince Vasily (1255).

The stone Nativity Church, which has survived to this day, was built in 1381–1382 commissioned by Prince Dmitry Donskoy.

In the 15th century, the monastery definitely existed and owned lands in Shelonskaya and Derevskaya pyatinas (administrative divisions); probably, its inhabitants came from noble families. After the annexation of Novgorod by Moscow, the lands were confiscated.

In the 15th–16th centuries, people who died while traveling, from pestilence or an unnatural death, including those executed, as well as the poor were buried in the vicinity of the monastery. On Thursday of the seventh week after Easter, the feast called Semik (from “sem” — “seven”), all those buried there were commemorated and a cross procession around the potter’s fields took place.

As a result of a fire in 1547, the monastery bell tower collapsed and the church and refectory burned down.

By 1615, the Nativity Church with a side chapel and a wooden refectory were transferred to the Antoniev Monastery, which used its own funds to restore them by the decree of voivode Semyon Urusov. In 1649 the monastery regained its status, but in 1764 it was abolished. The Nativity Church became a parish, and then a cemetery church.

After the revolution, the church was under protection of the Society of Lovers of Antiquity; in the 1940s and 1950s it was restored. In the 1970s and 1980s it was renovated according to the project of Ninel Nikolayevna Kuzmina and Lyubov Mitrofanovna Shulyak.

The architecture of the church, typical of the 14th century, is distinguished by some “negligence”: asymmetry and curved corners point to a low quality of construction. Researchers compare the style of frescoes of the late 14th century with the Morava tradition, widespread in Serbia. Despite the fires and renovations, they have been preserved quite well.

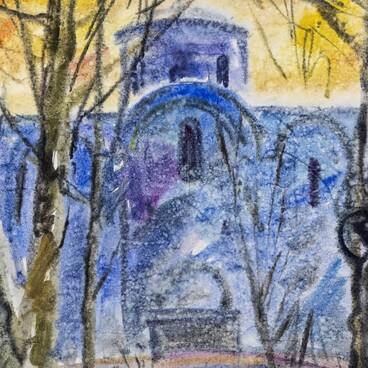

Semyon Ivanovich Pustovoytov, a graduate of the Odessa Art School and a veteran of the Great Patriotic War, had the opportunity to observe both the destruction and the revival of the ancient Novgorod architecture, and his watercolors make one see in these monuments a living history worthy of care and respect.

The archaeologist and ethnographer Ruf Gavrilovich Ignatiev, based on the hagiography of the venerable Alfanov brothers (the late 14th — early 15th century), believes that the Nativity Monastery was founded in the 12th century. The archaeologist Ivan Kupriyanovich Kupriyanov, however, considers their 17th-century hagiography historically unreliable.

The Novgorod First Chronicle reports the exact year when, most likely, a wooden church was constructed (1226), but does not mention the monastery.

In the 13th century, the church is referenced to in connection with potter’s fields (common graves; 1230) constructed there and the conflict of the Novgorodians with Alexander, the father of the exiled Prince Vasily (1255).

The stone Nativity Church, which has survived to this day, was built in 1381–1382 commissioned by Prince Dmitry Donskoy.

In the 15th century, the monastery definitely existed and owned lands in Shelonskaya and Derevskaya pyatinas (administrative divisions); probably, its inhabitants came from noble families. After the annexation of Novgorod by Moscow, the lands were confiscated.

In the 15th–16th centuries, people who died while traveling, from pestilence or an unnatural death, including those executed, as well as the poor were buried in the vicinity of the monastery. On Thursday of the seventh week after Easter, the feast called Semik (from “sem” — “seven”), all those buried there were commemorated and a cross procession around the potter’s fields took place.

As a result of a fire in 1547, the monastery bell tower collapsed and the church and refectory burned down.

By 1615, the Nativity Church with a side chapel and a wooden refectory were transferred to the Antoniev Monastery, which used its own funds to restore them by the decree of voivode Semyon Urusov. In 1649 the monastery regained its status, but in 1764 it was abolished. The Nativity Church became a parish, and then a cemetery church.

After the revolution, the church was under protection of the Society of Lovers of Antiquity; in the 1940s and 1950s it was restored. In the 1970s and 1980s it was renovated according to the project of Ninel Nikolayevna Kuzmina and Lyubov Mitrofanovna Shulyak.

The architecture of the church, typical of the 14th century, is distinguished by some “negligence”: asymmetry and curved corners point to a low quality of construction. Researchers compare the style of frescoes of the late 14th century with the Morava tradition, widespread in Serbia. Despite the fires and renovations, they have been preserved quite well.

Semyon Ivanovich Pustovoytov, a graduate of the Odessa Art School and a veteran of the Great Patriotic War, had the opportunity to observe both the destruction and the revival of the ancient Novgorod architecture, and his watercolors make one see in these monuments a living history worthy of care and respect.