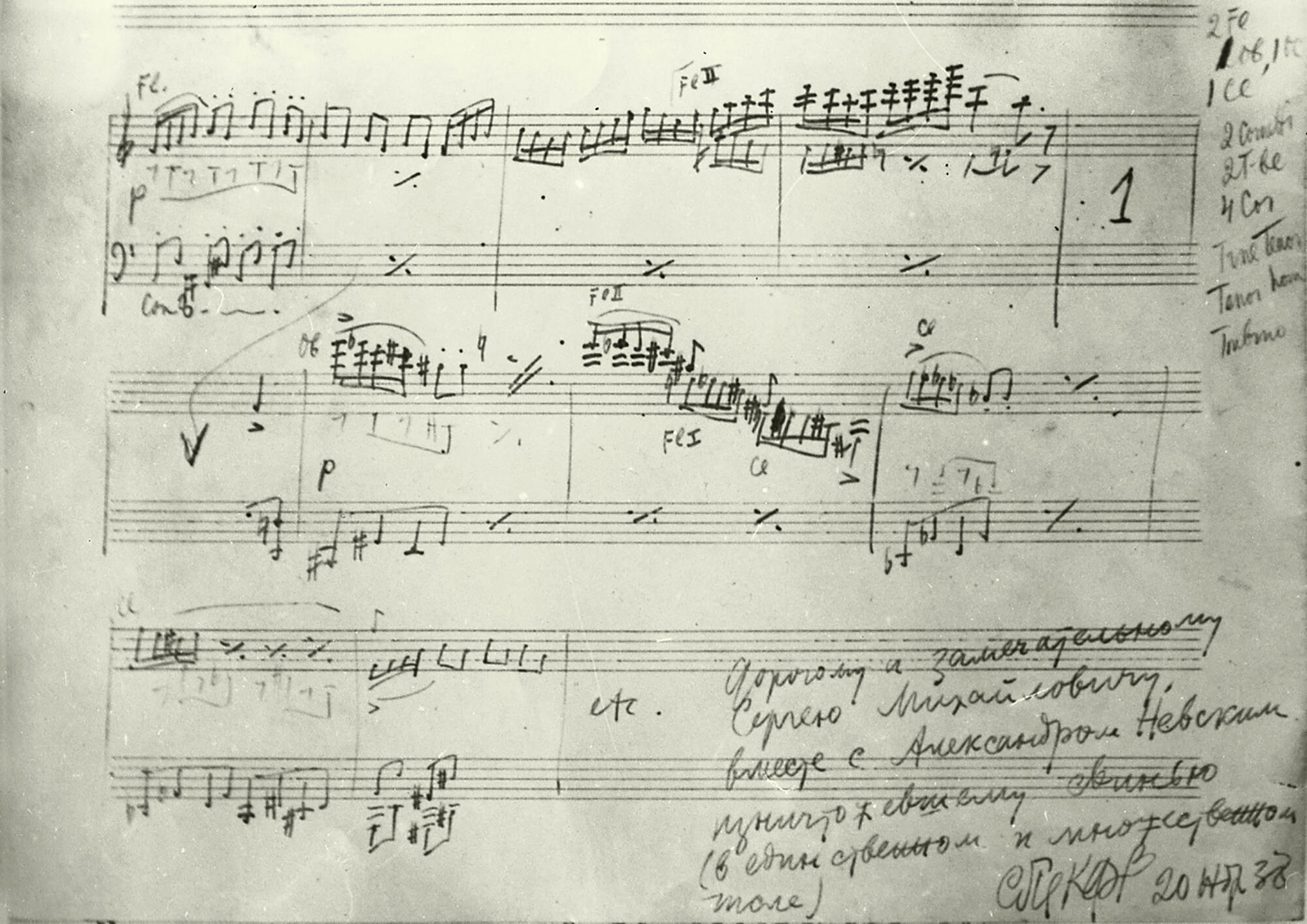

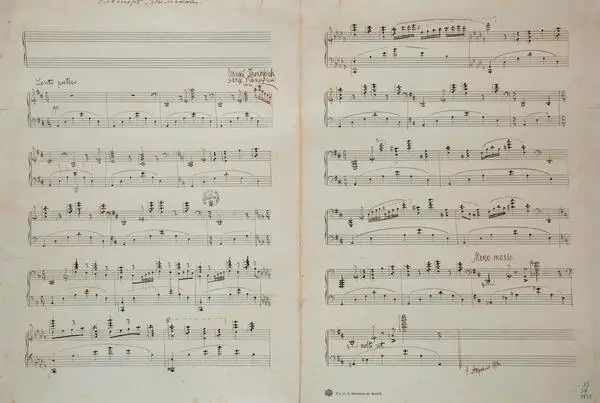

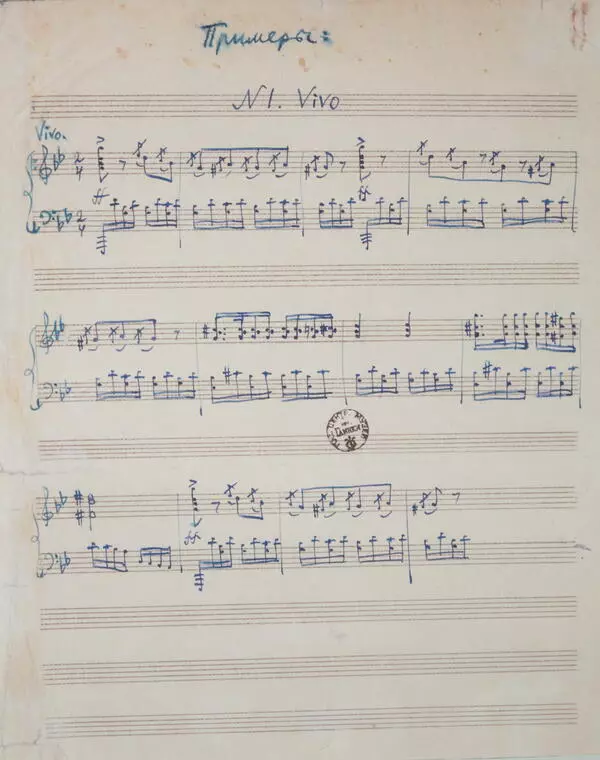

This sheet was gifted to the director by Sergei ProkOfiev (1891–1953) after the filming of ‘Alexander NEvsky’ was concluded on November 20, 1938. It was displayed in Sergei Eisenstein’s study at his apartment on PotYlikha Street. In the bottom right corner of a musical autograph there is a dedication, handwritten by the composer: “To my dear and wonderful Sergei Mikhailovich, who has eliminated the pig (singular and multiple) together with Alexander Nevsky. SPRKFV Nov. 20, '38.”

“Everything unsteady, transient, and incidentally capricious has been banished from the creations of the composer, like the vowels from his signature, ” Sergei Eisenstein later wrote in his 1942–1944 essay “PRKFV” about his friend and ally. He also linked Prokofiev’s approach to the areas of art where artists similarly get in touch with the ‘structural mystery of the phenomenon’, like the byzantine iconography canon, the search of meaning by avant-garde artists, and of course with the cinema, which has been organically complimented by ‘Prokofiev’s incandescent creation of music and light’.

Picture “Alexander Nevsky” was the first joint work of Eisenstein and Prokofiev. Later on, they have also created “IvAn GrOzny” together. “Alexander Nevsky” hit theaters on December 1, 1938, and the movie’s creators were already celebrating their success earlier in November when the movie was approved for public release by all the relevant state agencies.

Scholars of Eisenstein’s work suggest that the “pig” the composer mentioned in the dedication on his musical autograph might have referred to Boris ShumyAtsky, head of the General Directorate of Film Industry, who had a bone to pick with Eisenstein. That man has personally orchestrated a campaign against Eisenstein and even personally submitted a motion to arrest the director to Joseph Stalin. Stalin did not sign off on that motion, and moreover, gave the director an opportunity to “recuperate” (after his previous film, “Bezhin Lug”, was barred from public release in 1937): Stalin suggested to the director to create a movie with military and patriotic themes.

Eisenstein has used this opportunity to work with a script about Alexander Nevsky that has been suggested to him. Working within a limited time frame and with limited technical resources, the director’s choice of plot devices was limited. For that reason, Eisenstein went with the ‘canons’ of living icons, murals, and traditional luboks. Within this canon, he could masterfully conduct his creative experiments and finally release his first complete movie with sound.

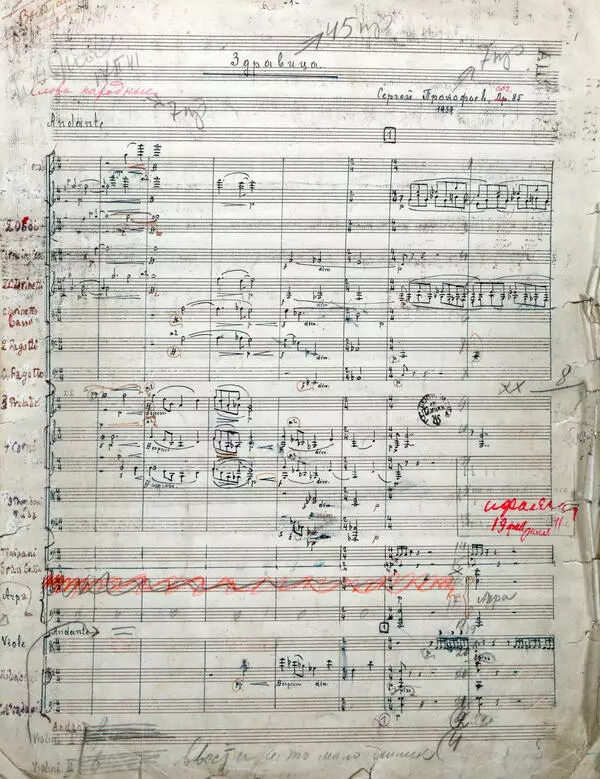

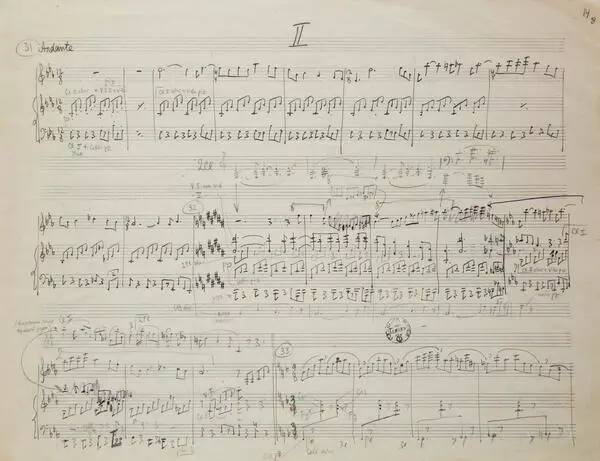

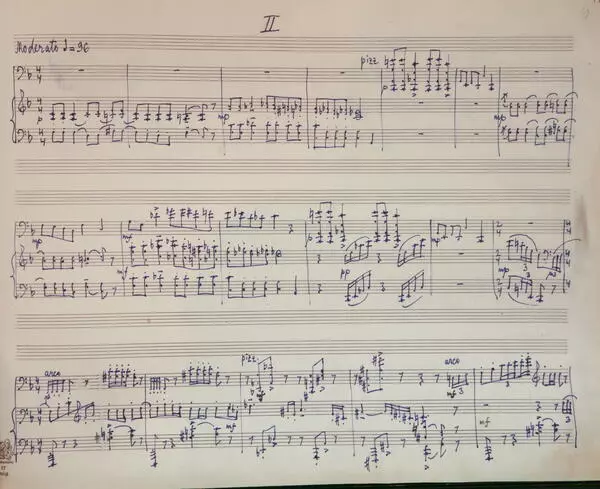

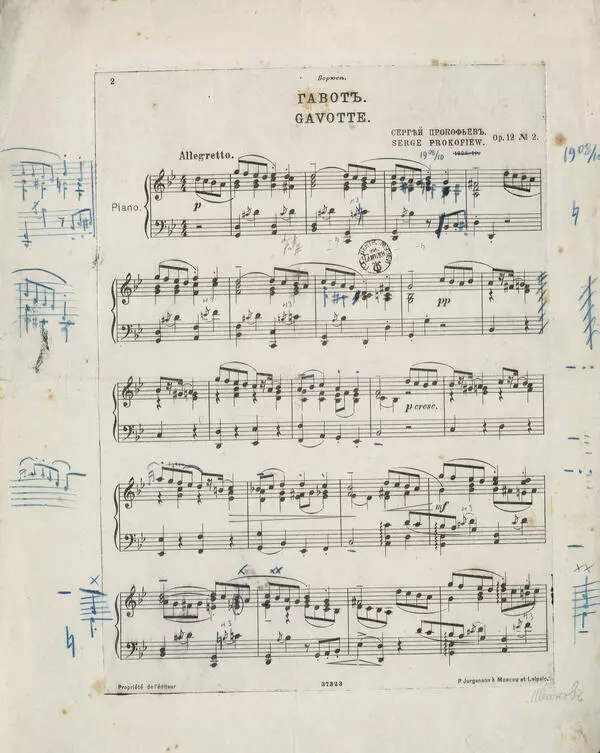

Original music sheet written and signed by Prokofiev in 1938 was lost in the 1960's. PEra AtAsheva, Sergei Eisenstein’s widow, had a black-and-white photocopy in her possession — it was made for the 3rd book in the complete collection of Eisenstein’s essays. This photocopy is stored in the Film Museum on the rights of the original. Music scholars SvetlAna SavEnko and MarIna NEstieva have helped to decipher a melody roughly outlined by the composer. It’s the theme of folk musicians. At the pivotal moment of the Battle on the Ice they were playing their music over the enemy’s music, inspiring the Russian warriors with the whimsical tunes played on pipes and tambourines. Second variation of this melody appears in the scene of victory celebrations at the end of the film. Savenko suggests that the sheet contains this melody specifically: Prokofiev has transformed the theme, making it sound ‘astral’. Shot of the old jester with his pipes turning to the audience in the frame is reminiscent of the famous frontal shot of the guns aboard the Potyomkin. During the transition to the general shot of the celebrating crowd, the orchestra comes in to support the pipes and tambourines.

“Everything unsteady, transient, and incidentally capricious has been banished from the creations of the composer, like the vowels from his signature, ” Sergei Eisenstein later wrote in his 1942–1944 essay “PRKFV” about his friend and ally. He also linked Prokofiev’s approach to the areas of art where artists similarly get in touch with the ‘structural mystery of the phenomenon’, like the byzantine iconography canon, the search of meaning by avant-garde artists, and of course with the cinema, which has been organically complimented by ‘Prokofiev’s incandescent creation of music and light’.

Picture “Alexander Nevsky” was the first joint work of Eisenstein and Prokofiev. Later on, they have also created “IvAn GrOzny” together. “Alexander Nevsky” hit theaters on December 1, 1938, and the movie’s creators were already celebrating their success earlier in November when the movie was approved for public release by all the relevant state agencies.

Scholars of Eisenstein’s work suggest that the “pig” the composer mentioned in the dedication on his musical autograph might have referred to Boris ShumyAtsky, head of the General Directorate of Film Industry, who had a bone to pick with Eisenstein. That man has personally orchestrated a campaign against Eisenstein and even personally submitted a motion to arrest the director to Joseph Stalin. Stalin did not sign off on that motion, and moreover, gave the director an opportunity to “recuperate” (after his previous film, “Bezhin Lug”, was barred from public release in 1937): Stalin suggested to the director to create a movie with military and patriotic themes.

Eisenstein has used this opportunity to work with a script about Alexander Nevsky that has been suggested to him. Working within a limited time frame and with limited technical resources, the director’s choice of plot devices was limited. For that reason, Eisenstein went with the ‘canons’ of living icons, murals, and traditional luboks. Within this canon, he could masterfully conduct his creative experiments and finally release his first complete movie with sound.

Original music sheet written and signed by Prokofiev in 1938 was lost in the 1960's. PEra AtAsheva, Sergei Eisenstein’s widow, had a black-and-white photocopy in her possession — it was made for the 3rd book in the complete collection of Eisenstein’s essays. This photocopy is stored in the Film Museum on the rights of the original. Music scholars SvetlAna SavEnko and MarIna NEstieva have helped to decipher a melody roughly outlined by the composer. It’s the theme of folk musicians. At the pivotal moment of the Battle on the Ice they were playing their music over the enemy’s music, inspiring the Russian warriors with the whimsical tunes played on pipes and tambourines. Second variation of this melody appears in the scene of victory celebrations at the end of the film. Savenko suggests that the sheet contains this melody specifically: Prokofiev has transformed the theme, making it sound ‘astral’. Shot of the old jester with his pipes turning to the audience in the frame is reminiscent of the famous frontal shot of the guns aboard the Potyomkin. During the transition to the general shot of the celebrating crowd, the orchestra comes in to support the pipes and tambourines.

A caricature sculpture of Sergei Prokofiev produced by the Kukryniksy artistic collective is also exhibited in the Museum of Cinema. According to an account given by Pera Atasheva, around 1938, Sergei Mikhailovich has purchased the caricature scultures of Prokofiev and Meyerhold at the crockery shop on Arbat St. Upon making the purchase, Eisenstein called the composer, saying: ‘Sergei Sergeevich, I never knew they made you into a piece of crockery.’