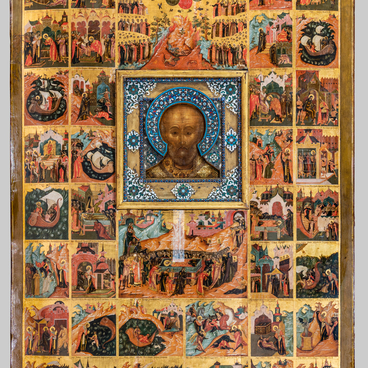

The icon ‘Weep Not for Me, Mother’ was created by the Palekh artist Ilya Balyakin. He painted it for the Holy Cross Church in 1769. It is considered the first known signed and dated icon in Palekh.

The name of the icon derives from the chants of Holy Week. During the Holy Week, canons—songs that praise the saints—are sung in churches. The canon songs consist of different parts with their own names: the irmos (the initial part of an ode) and the troparia (the subsequent stanzas). The icon ‘Weep Not For Me, Mother’ illustrates one of the irmoi of the canon sung during Holy Saturday before Easter: ‘Weep not for me, Mother, seeing how your son, conceived without a seed, lies in a tomb; I shall rise and be glorified, and as God, I shall exalt all who speak of thee with faith and love.’

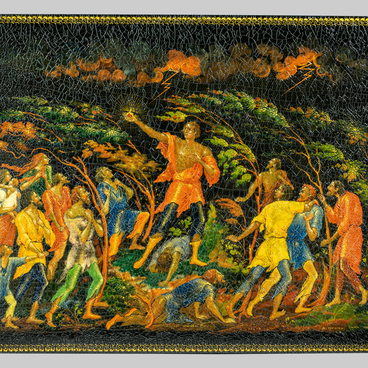

This icon is considered the best example of the so-called Fryazhsky style (from an Old Russian ‘Fryazin, ’ a name used for immigrants from Southern Europe of Roman origin) in the museum’s collection. Icons painted in the Fryazhsky style were distinguished by the authenticity of landscape, architecture, and figures. The style was founded by the Russian artists who drew inspiration from European paintings: during the Renaissance, Western artists started using light and shadow to create volume and linear perspective techniques to convey depth. It first appeared in Russia in the 17th century.

When making the icon, Ilya Balyakin used a Western European religious painting depicting the Lamentation of Christ as reference. The artist wanted to focus the attention on the face of the Mother of God. She is young and beautiful. There is no dramatic tension in her face, only light sadness. The head of Jesus is resting quietly on her hand: the Savior is free from the torment of the cross. The artist depicted his figure from several angles. This creates the illusion that the body is not sliding down, but is actually rising up.

As dictated by the icon painting rules, the scene takes place against the background of an architectural and natural landscape. But the shapes are more realistic than was generally accepted by the Old Russian tradition. For example, the hills are depicted without the ledge-like elements typical of Russian icons. In addition, the artist decided not to paint the elements of the landscape with gold, as was customary for the Palekh icons.

Interestingly, the author painted the faces of the saints in a soft and graphic manner of Old Russian artists. Balyakin used light strokes of white paint to highlight certain areas and create the illusion of volume through the play of light and shadow. This technique was typical of the Palekh icons created in the second half of the 18th century.

The name of the icon derives from the chants of Holy Week. During the Holy Week, canons—songs that praise the saints—are sung in churches. The canon songs consist of different parts with their own names: the irmos (the initial part of an ode) and the troparia (the subsequent stanzas). The icon ‘Weep Not For Me, Mother’ illustrates one of the irmoi of the canon sung during Holy Saturday before Easter: ‘Weep not for me, Mother, seeing how your son, conceived without a seed, lies in a tomb; I shall rise and be glorified, and as God, I shall exalt all who speak of thee with faith and love.’

This icon is considered the best example of the so-called Fryazhsky style (from an Old Russian ‘Fryazin, ’ a name used for immigrants from Southern Europe of Roman origin) in the museum’s collection. Icons painted in the Fryazhsky style were distinguished by the authenticity of landscape, architecture, and figures. The style was founded by the Russian artists who drew inspiration from European paintings: during the Renaissance, Western artists started using light and shadow to create volume and linear perspective techniques to convey depth. It first appeared in Russia in the 17th century.

When making the icon, Ilya Balyakin used a Western European religious painting depicting the Lamentation of Christ as reference. The artist wanted to focus the attention on the face of the Mother of God. She is young and beautiful. There is no dramatic tension in her face, only light sadness. The head of Jesus is resting quietly on her hand: the Savior is free from the torment of the cross. The artist depicted his figure from several angles. This creates the illusion that the body is not sliding down, but is actually rising up.

As dictated by the icon painting rules, the scene takes place against the background of an architectural and natural landscape. But the shapes are more realistic than was generally accepted by the Old Russian tradition. For example, the hills are depicted without the ledge-like elements typical of Russian icons. In addition, the artist decided not to paint the elements of the landscape with gold, as was customary for the Palekh icons.

Interestingly, the author painted the faces of the saints in a soft and graphic manner of Old Russian artists. Balyakin used light strokes of white paint to highlight certain areas and create the illusion of volume through the play of light and shadow. This technique was typical of the Palekh icons created in the second half of the 18th century.