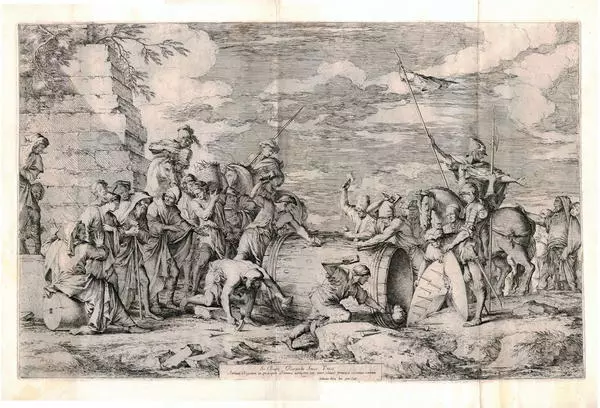

‘Bandits Attacking in the Mountains’ was painted by an Italian artist Salvator Rosa. The painting is typical of his style as it shows a scene with bandits: they ambush the travelers from their hiding place in the mountain gorge.

Rosa emphasized the tension of the scene with sharp contrasts of light and shadow, and the figures’ red robes added bright accents to the painting. The violence and swiftness of the battle were intensified by the choice of technique: the artist painted with ease leaving visible brush strokes on the surface of the canvas.

Landscapes occupy a special place in Rosa’s artwork. He based his paintings on the sketches that he made during his travels. Studying closely the world around him, Rosa would carefully render the detail he had observed, such as lopsided trees and sharp rock ledges. However, he did not simply copy real-life scenes, but rather created fictitious and somewhat idealized compositions interspersed with vivid impressions of nature.

The artist’s bold and even a little edgy manner of painting struck a chord with the following generations. His legacy became a source of inspiration for romantic painters. There is even an expression — à la Salvator Rosa. In the 18th century, that could be said about paintings that depicted distinctive sharp cliffs, dry trees, waterfalls, and bandits. Claude-Joseph Vernet, a French landscape painter, even designated two of his landscapes as being à la Salvator Rosa in the catalogue he had put together for the period of 1735–1788.

During his colorful life, Rosa lived and worked in Naples, Rome and Florence at the court of Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici. A lot of rumors circulated around his name even when he was still alive, including the one about him once being captured by a gang of bandits. A prominent expert of Rosa’s artwork Elena Sharnova wrote that such legends in his biography “go hand in hand with the documented proof of Rosa”s activities as an actor, liberal pamphleteer, gifted poet, and music improviser.”

“Bandits Attacking in the Mountains” was donated to the museum in 1962 from the collection of Andrey Likhachov. Prior to that, it was part of the exposition of the National Museum of the Republic of Tatarstan.

Rosa emphasized the tension of the scene with sharp contrasts of light and shadow, and the figures’ red robes added bright accents to the painting. The violence and swiftness of the battle were intensified by the choice of technique: the artist painted with ease leaving visible brush strokes on the surface of the canvas.

Landscapes occupy a special place in Rosa’s artwork. He based his paintings on the sketches that he made during his travels. Studying closely the world around him, Rosa would carefully render the detail he had observed, such as lopsided trees and sharp rock ledges. However, he did not simply copy real-life scenes, but rather created fictitious and somewhat idealized compositions interspersed with vivid impressions of nature.

The artist’s bold and even a little edgy manner of painting struck a chord with the following generations. His legacy became a source of inspiration for romantic painters. There is even an expression — à la Salvator Rosa. In the 18th century, that could be said about paintings that depicted distinctive sharp cliffs, dry trees, waterfalls, and bandits. Claude-Joseph Vernet, a French landscape painter, even designated two of his landscapes as being à la Salvator Rosa in the catalogue he had put together for the period of 1735–1788.

During his colorful life, Rosa lived and worked in Naples, Rome and Florence at the court of Giovanni Carlo de’ Medici. A lot of rumors circulated around his name even when he was still alive, including the one about him once being captured by a gang of bandits. A prominent expert of Rosa’s artwork Elena Sharnova wrote that such legends in his biography “go hand in hand with the documented proof of Rosa”s activities as an actor, liberal pamphleteer, gifted poet, and music improviser.”

“Bandits Attacking in the Mountains” was donated to the museum in 1962 from the collection of Andrey Likhachov. Prior to that, it was part of the exposition of the National Museum of the Republic of Tatarstan.