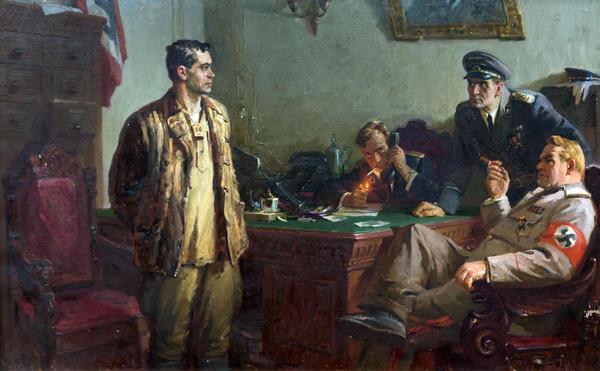

In 1950, Haris Yakopov by recommendation of composer Nazib Zhiganov contemplated a large canvas devoted to a Tatar poet Musa Dzhalil. The painting Before the Sentence turned out to be a masterpiece of the artist’s early period. “I decided to show Musa Dzhalil among the Nazis at the moment of the poet”s interrogation because it seemed the right situation to show the confrontation of the opposites…I intended to show moral superiority of the hero poet over his executioners, his true grit. The image of the poet should have resonated with his immortal lines: “I will never bend the knee to you, hangman, never bend the knee/ I am in your captivity, a slave in your prison/ Still that is not the reason /for me to bend the knee/ My time will come and you will sever my head, hell-kite/ I will die, but I will die upright” “, the artist recalled.

In 1942, Musa Zalilov better known as Musa Dzhalil went to the Leningrad frontline as a war correspondent. In the same year, heavily wounded he was taken prisoner. There, he was assigned to the Idel-Ural legion formed by the Nazis from Soviet prisoners for the purpose of fighting the Red Army. Eleven of the twelve members of the Legion used the opportunity and posing as fighters against the Red Army initiated underground work against the Nazis.

Dzhalil who won the confidence of his captors was entrusted with education and propaganda work and he used that cover to organize the war prisoners” escape and successfully recruited more underground resistance fighters. In 1943, the entire resistance organization was arrested and thrown to the Moabit Prison in Berlin, where they all were incessantly interrogated and tortured.

Dzhalil composed verses in prison, which helped him to hold on. In 1944, he was guillotined together with the rest of his comrades of resistance.

Yakupov painted Dzhalil’s interrogation scene. It is obvious that the main character in the picture will receive a harsh sentence. However, the doomed man looks calm, even majestic. His youth, confidence, and inner strength make him the winner. His dark-complexioned broad face with well-defined eyebrows, his proud demeanor, upright posture, and level gaze are highly expressive. The Nazis conducting the interrogation are no less expressive. Their images have no trace of grotesqueness.

In this work, Yakupov followed the tradition of the masers of realistic art. The faces, postures, and gestures of the characters, as well as the picture’s color scheme were calculated down to the minute detail. Light plays an important role: illuminating some details and leaving others in the shade the artist accentuated the difference between the picture’s main and peripheral parts.

In 1942, Musa Zalilov better known as Musa Dzhalil went to the Leningrad frontline as a war correspondent. In the same year, heavily wounded he was taken prisoner. There, he was assigned to the Idel-Ural legion formed by the Nazis from Soviet prisoners for the purpose of fighting the Red Army. Eleven of the twelve members of the Legion used the opportunity and posing as fighters against the Red Army initiated underground work against the Nazis.

Dzhalil who won the confidence of his captors was entrusted with education and propaganda work and he used that cover to organize the war prisoners” escape and successfully recruited more underground resistance fighters. In 1943, the entire resistance organization was arrested and thrown to the Moabit Prison in Berlin, where they all were incessantly interrogated and tortured.

Dzhalil composed verses in prison, which helped him to hold on. In 1944, he was guillotined together with the rest of his comrades of resistance.

Yakupov painted Dzhalil’s interrogation scene. It is obvious that the main character in the picture will receive a harsh sentence. However, the doomed man looks calm, even majestic. His youth, confidence, and inner strength make him the winner. His dark-complexioned broad face with well-defined eyebrows, his proud demeanor, upright posture, and level gaze are highly expressive. The Nazis conducting the interrogation are no less expressive. Their images have no trace of grotesqueness.

In this work, Yakupov followed the tradition of the masers of realistic art. The faces, postures, and gestures of the characters, as well as the picture’s color scheme were calculated down to the minute detail. Light plays an important role: illuminating some details and leaving others in the shade the artist accentuated the difference between the picture’s main and peripheral parts.