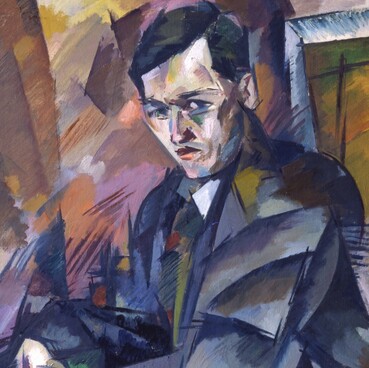

Nikolai Guschin, like many of his contemporary creators, was fascinated by the idea of bringing painting ‘to the brink of two elements - music and words’, tried to create ‘visible music’, and called this goal ‘interesting and subtle.’ Moods that are difficult to express in words, fantastic dreams, vague associations - these themes run through not only his ‘flagship’ musical paintings, such as Nocturne, Moonlight Sonata (both in the A.N. Radishchev Saratov State Art Museum), or Bach’s Music (private collection), but also in many of his landscapes. In the paintings in The Four Seasons cycle, and in his small landscape sketches, we seem to hear the cheerful green noises of springtime, the golden ringing of summer, the sad crimson violins of autumn, and the jingling chords of winter. My Symphony, which was created half a century after the first experiments with embodying the idea of synthesizing painting, music, and poetry, recaps the artist’s search. Guschin worked on it for several years, creating more than ten versions on one canvas. One of his friends recalled how one evening, looking at the picture and impressing it on his memory, the next morning he came up with another version.

During the night, the portrait, while retaining the composition that had immediately been found, changed dramatically, and was spiritedly redone by the artist. The photograph, which had been made and then miraculously kept by some unknown person, ‘memorized’ one of these options, and then completely disappeared under a layer of paint.

Konstantin Korovin and Sergei Malyutin became his mentors in art, and he counted Vasiliy Kamenskiy from the city of Perm, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and David Burlyuk among his friends. Trips to Europe and America, World War I, various revolutions - many events were compressed into several years of his life (1914-1918).

Nikolai Guschin, like his beloved poets, philosophers, and artists, felt ‘irrelevant’ at home, and were carried away by a wave of emigration. Another life began - a wandering one (1918-1947). Siberia, China, Paris, Monaco… There were successes, exhibitions, and prosperity, but his soul yearned for Russia. During the short post-victory ‘Stalinist thaw’ in October 1947, Guschin managed to go back to his homeland. From that time until the end, his life was completely connected with the Volga and Saratov.

The self-portraits done by N.M. Guschin - as different as the periods of his life, and all crammed into one destiny - are arranged in a genuine creative confession made by the artist. Earlier drawings almost always capture the right profile of a handsome, sad face. Inner Gaze (1941, A.N. Radishchev Saratov State Art Museum), painted while in exile, is a self-portrait with sharp facial features and a ‘stony’ chin, where the artist is mercilessly thrown to the very bottom of his soul. ‘Your fate is stamped like a medal in your stern countenance, ” were the surprisingly accurate words found by French critic for this portrait. A Psychological Sketch (1955, A.N. Radishchev Saratov State Art Museum), was painted in Saratov by this time, and in some mysterious way managed to appear at a regional art exhibition in 1955 during that time when there was censorship. Judging by what people remember and the guestbook, it gave the impression of an “unexploded bomb” against the backdrop of “production” paintings and serene landscapes. My Symphony is the last self- portrait that Guschin did, the culmination of his creative quest and a spiritual testament left to us.

During the night, the portrait, while retaining the composition that had immediately been found, changed dramatically, and was spiritedly redone by the artist. The photograph, which had been made and then miraculously kept by some unknown person, ‘memorized’ one of these options, and then completely disappeared under a layer of paint.

Konstantin Korovin and Sergei Malyutin became his mentors in art, and he counted Vasiliy Kamenskiy from the city of Perm, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and David Burlyuk among his friends. Trips to Europe and America, World War I, various revolutions - many events were compressed into several years of his life (1914-1918).

Nikolai Guschin, like his beloved poets, philosophers, and artists, felt ‘irrelevant’ at home, and were carried away by a wave of emigration. Another life began - a wandering one (1918-1947). Siberia, China, Paris, Monaco… There were successes, exhibitions, and prosperity, but his soul yearned for Russia. During the short post-victory ‘Stalinist thaw’ in October 1947, Guschin managed to go back to his homeland. From that time until the end, his life was completely connected with the Volga and Saratov.

The self-portraits done by N.M. Guschin - as different as the periods of his life, and all crammed into one destiny - are arranged in a genuine creative confession made by the artist. Earlier drawings almost always capture the right profile of a handsome, sad face. Inner Gaze (1941, A.N. Radishchev Saratov State Art Museum), painted while in exile, is a self-portrait with sharp facial features and a ‘stony’ chin, where the artist is mercilessly thrown to the very bottom of his soul. ‘Your fate is stamped like a medal in your stern countenance, ” were the surprisingly accurate words found by French critic for this portrait. A Psychological Sketch (1955, A.N. Radishchev Saratov State Art Museum), was painted in Saratov by this time, and in some mysterious way managed to appear at a regional art exhibition in 1955 during that time when there was censorship. Judging by what people remember and the guestbook, it gave the impression of an “unexploded bomb” against the backdrop of “production” paintings and serene landscapes. My Symphony is the last self- portrait that Guschin did, the culmination of his creative quest and a spiritual testament left to us.