Alexander Vasilyevich Nikitenko came from the serfs of Count Nikolai Petrovich Sheremetev. His talent and perseverance allowed him to enter the world of great literature and become a censor and editor, who wrote articles on the history of literature and literary criticism. He also became a professor of the department of Russian literature and was made a member of the Academy of Sciences.

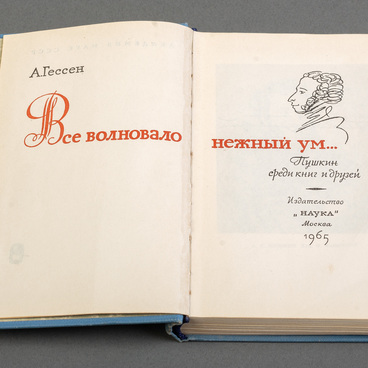

For a long time, he worked in institutions that censored printed publications, compiled notes for the charter of censorship, and was a censor himself. He was an independent and thoughtful man and was quite liberal toward some “questionable” works, which caused him occasional fines. Mingling with writers, Nikitenko was acquainted with Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, Vissarion Grigoryevich Belinsky, Nikolay Alekseyevich Nekrasov, Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol, Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev, Ivan Alexandrovich Goncharov, and others.

For almost half a century, Alexander Nikitenko had been keeping a diary, which proved to be an important cultural and historical document. The “Diary” together with the autobiographical “Notes” provide unique and unbiased information about the development of public opinion, literature, censorship, and journalism. Recording and analyzing significant events and impressions became a vital necessity for Nikitenko.

In 1851, while still keeping the “work-related” diary, Nikitenko began to transform the available materials into literary works, combining them in a book entitled “The Story about Me and What I Witnessed in Life”. Unfortunately, he never finished it. Before his death, Alexander Nikitenko asked his daughters to manage his manuscripts.

Between February 1889 and April 1892, excerpts from the “Diary” and “Notes” were published by Mikhail Ivanovich Semevsky in the “Russkaya Starina” (Russian Antiquity) journal.

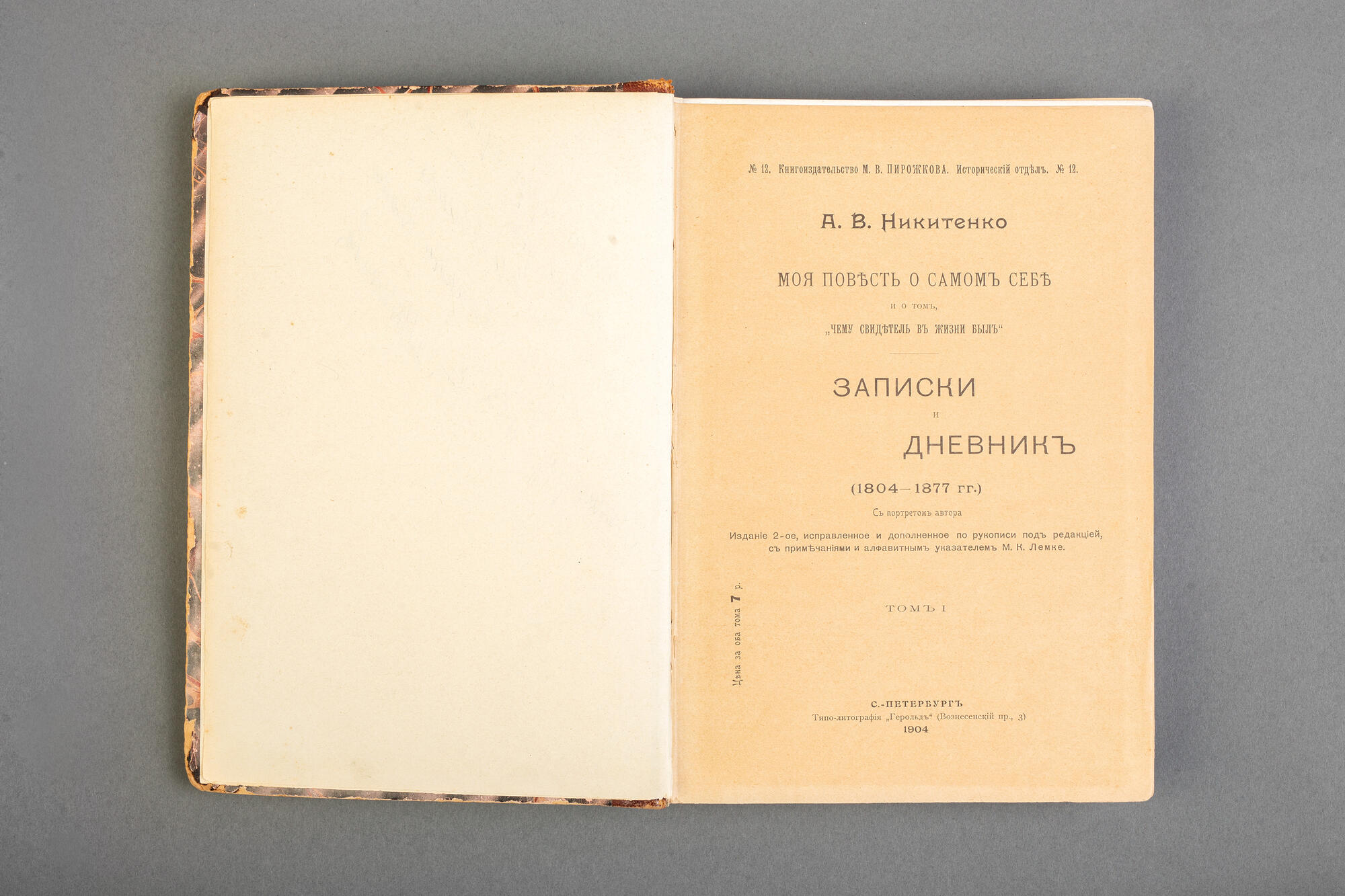

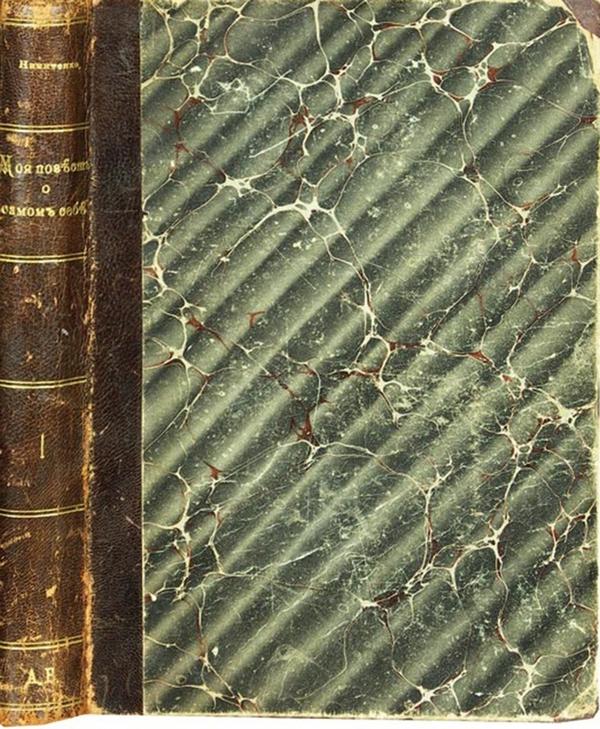

In 1904–1905, an expanded edition of the memoirs was first published under the editorship of the historian Mikhail Konstantinovich Lemke; half a century later, the three-volume “Diary”, edited by the critic and literary historian Iyeremiya Yakovlevich Aizenshtok, saw the light of day. The new 2005 three-volume edition included both the “Notes” and the “Diary”.

For a long time, he worked in institutions that censored printed publications, compiled notes for the charter of censorship, and was a censor himself. He was an independent and thoughtful man and was quite liberal toward some “questionable” works, which caused him occasional fines. Mingling with writers, Nikitenko was acquainted with Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin, Vissarion Grigoryevich Belinsky, Nikolay Alekseyevich Nekrasov, Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol, Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev, Ivan Alexandrovich Goncharov, and others.

For almost half a century, Alexander Nikitenko had been keeping a diary, which proved to be an important cultural and historical document. The “Diary” together with the autobiographical “Notes” provide unique and unbiased information about the development of public opinion, literature, censorship, and journalism. Recording and analyzing significant events and impressions became a vital necessity for Nikitenko.

In 1851, while still keeping the “work-related” diary, Nikitenko began to transform the available materials into literary works, combining them in a book entitled “The Story about Me and What I Witnessed in Life”. Unfortunately, he never finished it. Before his death, Alexander Nikitenko asked his daughters to manage his manuscripts.

Between February 1889 and April 1892, excerpts from the “Diary” and “Notes” were published by Mikhail Ivanovich Semevsky in the “Russkaya Starina” (Russian Antiquity) journal.

In 1904–1905, an expanded edition of the memoirs was first published under the editorship of the historian Mikhail Konstantinovich Lemke; half a century later, the three-volume “Diary”, edited by the critic and literary historian Iyeremiya Yakovlevich Aizenshtok, saw the light of day. The new 2005 three-volume edition included both the “Notes” and the “Diary”.