Constantin Westchiloff began his career as an artist as a pupil of Father Luka at the Valaam Monastery, taking lessons of painting. Afterwards, he enrolled into the school of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, and, later, to the Princess Tenishev School of Drawing where famous Russian artist Ilya Repin was a professor at the time. Repin became Westchiloff’s mentor, and for many years he helped the young painter. Thanks to his support, financial and otherwise, Westchiloff managed to complete the course at the Imperial Academy of Arts with success, take part in a few major exhibitions, and get first serious commissions.

Westchiloff was always fond of history, and, as time went by, he became a successful historical painter. His works were representative of the so-called “Russian style, ” which had its distinct features: treating images and motifs of ancient Russian architecture and decorative art.

Critics wrote about Westchiloff”s canvas The Trial of Archpriest Avvakum at the Patriarch”s Golden Chamber on May 13, 1666: “This is the centerpiece of the exhibition, an important creation of the brush. It should be in the Tretyakov Gallery, beside Surikov”s Boyarina Morozova. In addition to the vibrant expression that was rendered effectively, the picture has brilliant brushwork as another one of its merits.’ The artist was so infatuated with historical studies that after he had graduated from the Academy of Arts, he enrolled into the Imperial Archeology Institute. His course there was finished in 1908.

At some moment, however, Westchiloff began to work in a slipshod manner. He exhibited a few sloppy works that were harshly but deservedly criticized. Critic Nikolai Kravchenko came up with one of the widely circulated comments about Westchiloff in a 1911 issue of the New Times magazine: ‘Whoever stops loving his art, whoever can treat it with too much levity, loses every opportunity of creating anything serious, big, good.’

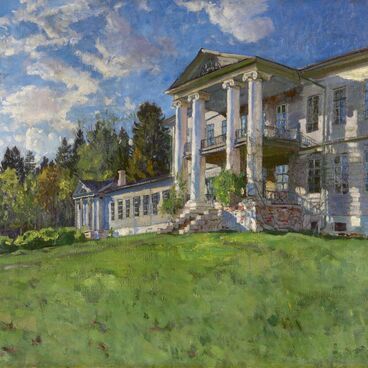

After a number of notorious flops, Westchiloff turned to landscape. He received a positon of painter at the Ministry of the Navy, painted seascapes and scenes of naval battles. The 1914 exhibition season was the artist’s triumph, as many critics praised his works in a new genre. For instance, the above-mentioned Nikolai Kravchenko wrote: “In some pieces, he is very colorful, very good in draughtsmanship, in the accuracy of tones. These works by Westchiloff are a step forward.”

After the February Revolution, the artist, unexpectedly for everyone, joined the Petrograd people’s militia, maintained order in the city streets, fought against marauders and profiteers. However, not a single important work did Westchiloff exhibit for the public in that period. In the 1920s, he emigrated from Russia, lived in France and in the U.S., where he organized occasional art shows, albeit rarely, and died, nearly forgotten, in 1945.

Westchiloff was always fond of history, and, as time went by, he became a successful historical painter. His works were representative of the so-called “Russian style, ” which had its distinct features: treating images and motifs of ancient Russian architecture and decorative art.

Critics wrote about Westchiloff”s canvas The Trial of Archpriest Avvakum at the Patriarch”s Golden Chamber on May 13, 1666: “This is the centerpiece of the exhibition, an important creation of the brush. It should be in the Tretyakov Gallery, beside Surikov”s Boyarina Morozova. In addition to the vibrant expression that was rendered effectively, the picture has brilliant brushwork as another one of its merits.’ The artist was so infatuated with historical studies that after he had graduated from the Academy of Arts, he enrolled into the Imperial Archeology Institute. His course there was finished in 1908.

At some moment, however, Westchiloff began to work in a slipshod manner. He exhibited a few sloppy works that were harshly but deservedly criticized. Critic Nikolai Kravchenko came up with one of the widely circulated comments about Westchiloff in a 1911 issue of the New Times magazine: ‘Whoever stops loving his art, whoever can treat it with too much levity, loses every opportunity of creating anything serious, big, good.’

After a number of notorious flops, Westchiloff turned to landscape. He received a positon of painter at the Ministry of the Navy, painted seascapes and scenes of naval battles. The 1914 exhibition season was the artist’s triumph, as many critics praised his works in a new genre. For instance, the above-mentioned Nikolai Kravchenko wrote: “In some pieces, he is very colorful, very good in draughtsmanship, in the accuracy of tones. These works by Westchiloff are a step forward.”

After the February Revolution, the artist, unexpectedly for everyone, joined the Petrograd people’s militia, maintained order in the city streets, fought against marauders and profiteers. However, not a single important work did Westchiloff exhibit for the public in that period. In the 1920s, he emigrated from Russia, lived in France and in the U.S., where he organized occasional art shows, albeit rarely, and died, nearly forgotten, in 1945.