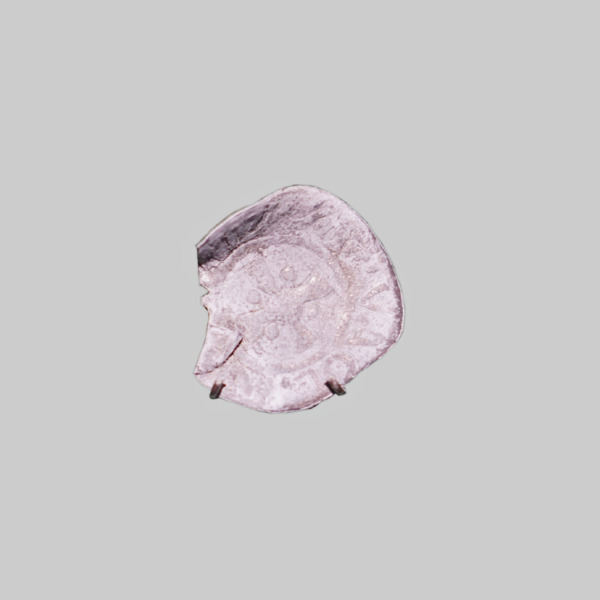

The coin was found on August 15, 1997 during archaeological excavations in the pre-Mongol layer to the north-east of the Annunciation Cathedral of the Kazan Kremlin. This finding helped researchers to clarify the dating of the early layer of Kazan, which was found in the Kremlin. The item has been attributed in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Berlin and Prague. The findings of the researchers confirmed the authenticity of the coin and its age.

The first to study the coin was Aleksandr Beliakov, a senior researcher in the Numismatics Department of the State Historical Museum, who figured out the time of minting — 10th-11th centuries. Archaeologists decided that the coin was silver, but in 1998 Vsevolod Potin from the Hermitage proved that it was almost pure lead. ‘The authenticity of the item, in terms of corrosion, is beyond doubt’, he wrote in the conclusion of the report. Also, according to the inscriptions on the coin, he determined its Czech origin.

The obverse of the coin depicts an equal-armed cross, and the reverse — a temple with two stairs. There is an inscription between its columns: IOA, which most likely meant the abbreviated name of the craftsman. Researchers have deciphered two inscriptions in Latin: ‘Wenceslas the Prince’ and ‘City of Prague’ and connected the Kazan finding with the period of the early history of the Czech people and the patron saint of the Czech Republic — Wenceslas — a prince from the Přemyslid dynasty (about 907~936).

The Head of the Numismatic Department of the National Museum of the Czech Republic, Jarmila Haskova, was invited to study the finding. She found that the type of the coin corresponds to the Carolingian temple type, which prevailed on banknotes in the eastern part of the German Empire in the Bavarian Swabia Region. Until the very beginning of the 11th century the coins were produced there, according to the Carolingian model XPISTIANA REGILIO — the type being imitated also by the Kazan finding.

But unlike the German model, the technical level of the Czech coin is much lower. It is almost entirely composed of lead with a small part of silver and, in fact, is worth nothing. Also, the hole on the coin’s edge indicated that the item was used as a decoration, and it could have got to Kazan bypassing trade routes.

The researchers came to the conclusion that the item was created not for economic goals, but for political ones: after all, the coin was a symbol of power, which carried recognizable symbols and an attribute of a strong state. Prince Wenceslas is considered one of the most far-sighted Slavic rulers of that time, and the minting of such coins puthim in line with the rulers of the German Empire.

The first to study the coin was Aleksandr Beliakov, a senior researcher in the Numismatics Department of the State Historical Museum, who figured out the time of minting — 10th-11th centuries. Archaeologists decided that the coin was silver, but in 1998 Vsevolod Potin from the Hermitage proved that it was almost pure lead. ‘The authenticity of the item, in terms of corrosion, is beyond doubt’, he wrote in the conclusion of the report. Also, according to the inscriptions on the coin, he determined its Czech origin.

The obverse of the coin depicts an equal-armed cross, and the reverse — a temple with two stairs. There is an inscription between its columns: IOA, which most likely meant the abbreviated name of the craftsman. Researchers have deciphered two inscriptions in Latin: ‘Wenceslas the Prince’ and ‘City of Prague’ and connected the Kazan finding with the period of the early history of the Czech people and the patron saint of the Czech Republic — Wenceslas — a prince from the Přemyslid dynasty (about 907~936).

The Head of the Numismatic Department of the National Museum of the Czech Republic, Jarmila Haskova, was invited to study the finding. She found that the type of the coin corresponds to the Carolingian temple type, which prevailed on banknotes in the eastern part of the German Empire in the Bavarian Swabia Region. Until the very beginning of the 11th century the coins were produced there, according to the Carolingian model XPISTIANA REGILIO — the type being imitated also by the Kazan finding.

But unlike the German model, the technical level of the Czech coin is much lower. It is almost entirely composed of lead with a small part of silver and, in fact, is worth nothing. Also, the hole on the coin’s edge indicated that the item was used as a decoration, and it could have got to Kazan bypassing trade routes.

The researchers came to the conclusion that the item was created not for economic goals, but for political ones: after all, the coin was a symbol of power, which carried recognizable symbols and an attribute of a strong state. Prince Wenceslas is considered one of the most far-sighted Slavic rulers of that time, and the minting of such coins puthim in line with the rulers of the German Empire.