Optical magnifiers were invented relatively late in history. Spectacles appeared in the thirteenth century, and microscopes three hundred years after that, at the end of the sixteenth century. The rapid spread and improvement of microscopes kicked off after Galileo perfected the telescope he had constructed and began using it as a sort of microscope. The invention consisted of two convex lenses mounted inside one tube. Focusing on the object under study was achieved due to a retractable tube, which made it possible to increase the image of the object being studied several times.

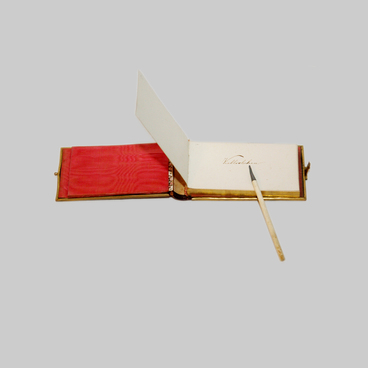

The genesis models of the microscope were very simple at first glance. But over time, with high society’s increased interest in science, they began to be made according to all the rules of decorative art, from expensive materials, including ivory, valuable wood, bronze, and decorated with special ingenuity. Their cases had embossed gold leather trimming.

Patrons of art created cabinets of curiosities and cabinets of rarities and ordered scientific instruments, including optical ones. With the development of science in the first half of the nineteenth century, there were a fairly large number of places where microscopes were produced. According to researchers, in 1820 an optics workshop at Kazan University produced high quality microscopes. The optical industry in Russia did not develop, since more often optical devices were imported from abroad.

The microscope from the Decembrists in Yalutorovsk exhibit consisted of two tubes of different diameters, located one above the other. In the upper tube there was a complex objective and eyepiece, and in the lower tube there was a mirror controlled by an external gear.

The device belonged to Vladimir Tokarev, heir to the exiled Yevgeny Obolensky. After the uprising in 1825, Obolensky was stripped of his princely title and sentenced to a life of hard labor in Siberia. Later, the term was reduced to 20, 15, and then 13 years. After surviving hard labor, he settled down in Yalutorovsk and married the maid Varvara Baranova. Like all Decembrists, Obolensky had a good education, helped local residents with advice, and after his restoration of rights, he participated in the work on the peasant reform of 1861.

The genesis models of the microscope were very simple at first glance. But over time, with high society’s increased interest in science, they began to be made according to all the rules of decorative art, from expensive materials, including ivory, valuable wood, bronze, and decorated with special ingenuity. Their cases had embossed gold leather trimming.

Patrons of art created cabinets of curiosities and cabinets of rarities and ordered scientific instruments, including optical ones. With the development of science in the first half of the nineteenth century, there were a fairly large number of places where microscopes were produced. According to researchers, in 1820 an optics workshop at Kazan University produced high quality microscopes. The optical industry in Russia did not develop, since more often optical devices were imported from abroad.

The microscope from the Decembrists in Yalutorovsk exhibit consisted of two tubes of different diameters, located one above the other. In the upper tube there was a complex objective and eyepiece, and in the lower tube there was a mirror controlled by an external gear.

The device belonged to Vladimir Tokarev, heir to the exiled Yevgeny Obolensky. After the uprising in 1825, Obolensky was stripped of his princely title and sentenced to a life of hard labor in Siberia. Later, the term was reduced to 20, 15, and then 13 years. After surviving hard labor, he settled down in Yalutorovsk and married the maid Varvara Baranova. Like all Decembrists, Obolensky had a good education, helped local residents with advice, and after his restoration of rights, he participated in the work on the peasant reform of 1861.