The model of a monument called Masks of Sorrow: Europe-Asia was acquired by the Museum thanks to the Sverdlovsk branch of the Memorial Society. The model was made by Ernst Neizvestny in Yekaterinburg in the early 1990s, after the sculptor returned from the United States where he had lived from 1976.

The artist’s intent was to make Masks of Sorrow: Europe-Asia the central monument of the Triangle of Sorrow dedicated to the memory of victims of Stalin’s purges. The plan was to install two of the monuments in Magadan and Vorkuta, and the third and central one in Yekaterinburg, on the boundary between Europe and Asia.

As Neizvestny put it, ‘the boundary between Europe and Asia is a certain symbolic boundary of horror and the Urals where the unfortunate victims of Stalin’s repressive regime were taken away’.

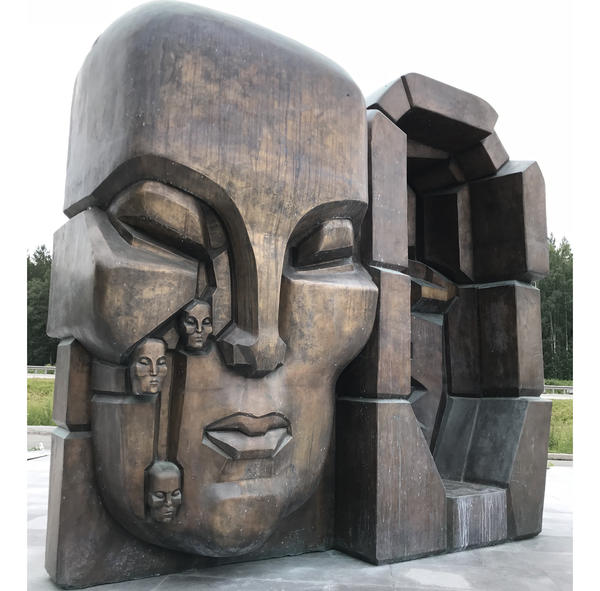

The Masks of Sorrow depict two faces, European and Asian, looking facing Europe and Asia, respectively. The tear running down the face has numerous other sorrowful faces. The meaning of the monument is obvious: at the first glance, it is a reminder about all people whose lives were destroyed by the system. But in actual fact, the message of the monument is much larger. Ernst Neizvestny sculpted them in memory of all the global tragedies of mankind in the 20th century, in memory of those living now and those who will come afterwards.

The project was never implemented in the format conceived by the author. The monument’s foundation stone was laid on the 12th kilometer of the Moscow HighWay only on April 9, 2015, on the 90th anniversary of the sculptor. The monument was inaugurated in November 2017, after the death of Ernst Neizvestny.

The Vorkuta monument has never been installed, whereas in Magadan the Mask of Sorrow was already in place in 1996. It is interesting not only for its unusual look: one can enter the monument and climb up a narrow staircase. Up there, the visitor will find themselves inside a cramped solitary confinement cell like those seen by thousands of victims of the Stalin regime.

The mask is a symbol that Ernst Neizvestny used in many of his sculptures. He wrote about it as follows: ‘Since ancient mystery plays, the ritual, mask, gesture and posture are inseparable and, penetrating each other, constitute a single whole. The grotesque is a product of freedom breaking up conventionality, immobility. The grotesque often looks fearful but it’s a victory over fear. The brain’s fear of death is overcome by belly’s laughter. Life and death are perceived not as antinomy but as a dialectic, integrated process of death and revival’.

The artist’s intent was to make Masks of Sorrow: Europe-Asia the central monument of the Triangle of Sorrow dedicated to the memory of victims of Stalin’s purges. The plan was to install two of the monuments in Magadan and Vorkuta, and the third and central one in Yekaterinburg, on the boundary between Europe and Asia.

As Neizvestny put it, ‘the boundary between Europe and Asia is a certain symbolic boundary of horror and the Urals where the unfortunate victims of Stalin’s repressive regime were taken away’.

The Masks of Sorrow depict two faces, European and Asian, looking facing Europe and Asia, respectively. The tear running down the face has numerous other sorrowful faces. The meaning of the monument is obvious: at the first glance, it is a reminder about all people whose lives were destroyed by the system. But in actual fact, the message of the monument is much larger. Ernst Neizvestny sculpted them in memory of all the global tragedies of mankind in the 20th century, in memory of those living now and those who will come afterwards.

The project was never implemented in the format conceived by the author. The monument’s foundation stone was laid on the 12th kilometer of the Moscow HighWay only on April 9, 2015, on the 90th anniversary of the sculptor. The monument was inaugurated in November 2017, after the death of Ernst Neizvestny.

The Vorkuta monument has never been installed, whereas in Magadan the Mask of Sorrow was already in place in 1996. It is interesting not only for its unusual look: one can enter the monument and climb up a narrow staircase. Up there, the visitor will find themselves inside a cramped solitary confinement cell like those seen by thousands of victims of the Stalin regime.

The mask is a symbol that Ernst Neizvestny used in many of his sculptures. He wrote about it as follows: ‘Since ancient mystery plays, the ritual, mask, gesture and posture are inseparable and, penetrating each other, constitute a single whole. The grotesque is a product of freedom breaking up conventionality, immobility. The grotesque often looks fearful but it’s a victory over fear. The brain’s fear of death is overcome by belly’s laughter. Life and death are perceived not as antinomy but as a dialectic, integrated process of death and revival’.