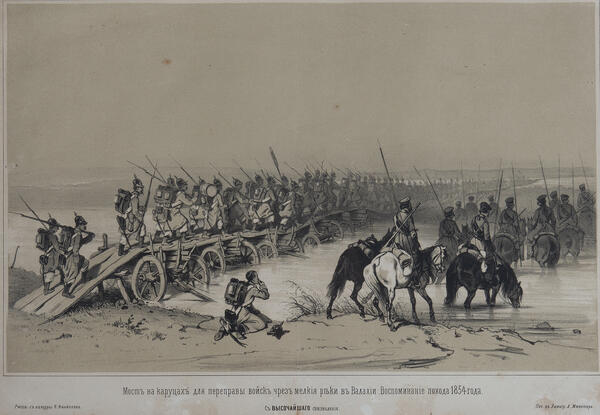

For Fyodor Tyutchev, the Crimean War was an event that had a profound influence on his worldview. The war lasted from 1853 to 1856. The fighting took place between the Russian Empire, on the one side, and a coalition of the British, French and Ottoman empires together with the Kingdom of Sardinia, on the other. The military conflict reached its peak in Crimea, so the war was called ‘Crimean’ in Russia. The reign of Nicholas I ended with a tragic defeat in this war and marked the beginning of reforms in Russia. The abolition of serfdom was the key milestone of this period, accompanied by large-scale reforms in almost all spheres of public life.

The poet was deeply worried about these events. ‘In order to create a hopeless situation like this,“Tyutchev wrote, “the monstrous stupidity of this unfortunate man was needed, during his twenty-year reign, he did not take advantage of anything and failed everything, starting a fight under the most impossible circumstances.”

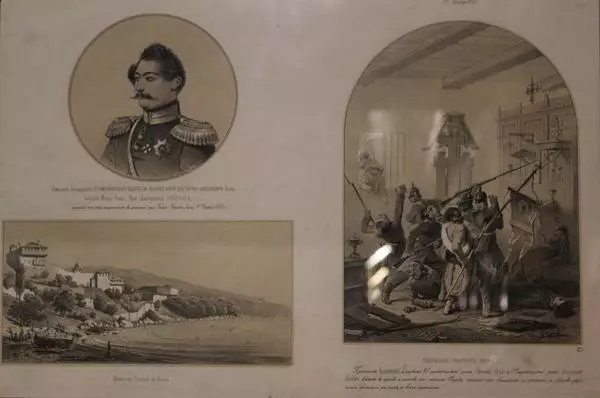

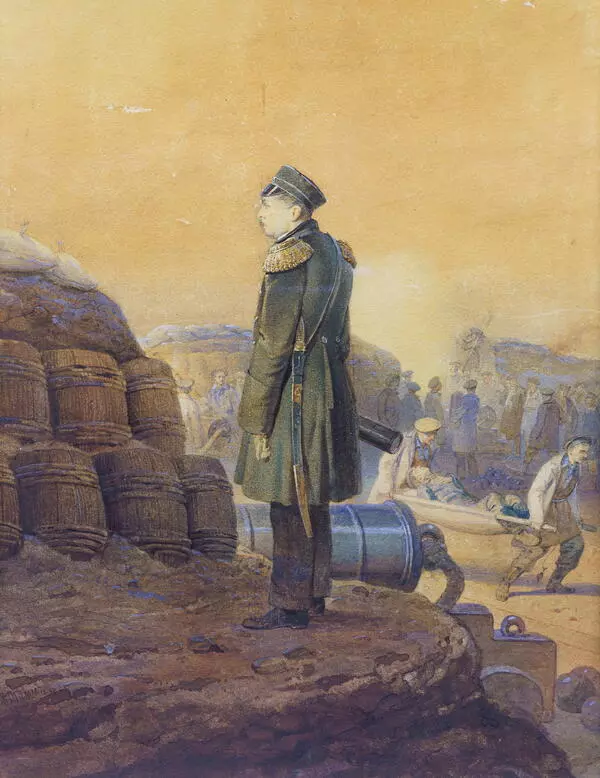

Tyutchev understood perfectly well that “the war had been lost by Russia before the first guns were fired.” “And these are the people who shape the destiny of Russia during one of the most terrible disasters…”, he complained. When the war was already going to an end, the poet wrote about the inability to tolerate “this arrant nonsense, terrible and buffoonery at the same time, this contradiction between people and their deeds, between what is and what should be, making you laugh or gnash your teeth.” Tyutchev took the defeat of the Russian army extremely hard, especially the fall of Sevastopol.

When the brother of the cook from Tyutchev’s estate went to the Crimea, the poet invited him to his office and talked to him for a long time. Although the poet had foreseen the entire course of events, he still had, in his own words, ‘the distressing and overwhelming impression of the Sevastopol catastrophe.’ On September 17, 1855, after the fall of Sevastopol, he wrote,

The poet was deeply worried about these events. ‘In order to create a hopeless situation like this,“Tyutchev wrote, “the monstrous stupidity of this unfortunate man was needed, during his twenty-year reign, he did not take advantage of anything and failed everything, starting a fight under the most impossible circumstances.”

Tyutchev understood perfectly well that “the war had been lost by Russia before the first guns were fired.” “And these are the people who shape the destiny of Russia during one of the most terrible disasters…”, he complained. When the war was already going to an end, the poet wrote about the inability to tolerate “this arrant nonsense, terrible and buffoonery at the same time, this contradiction between people and their deeds, between what is and what should be, making you laugh or gnash your teeth.” Tyutchev took the defeat of the Russian army extremely hard, especially the fall of Sevastopol.

When the brother of the cook from Tyutchev’s estate went to the Crimea, the poet invited him to his office and talked to him for a long time. Although the poet had foreseen the entire course of events, he still had, in his own words, ‘the distressing and overwhelming impression of the Sevastopol catastrophe.’ On September 17, 1855, after the fall of Sevastopol, he wrote,