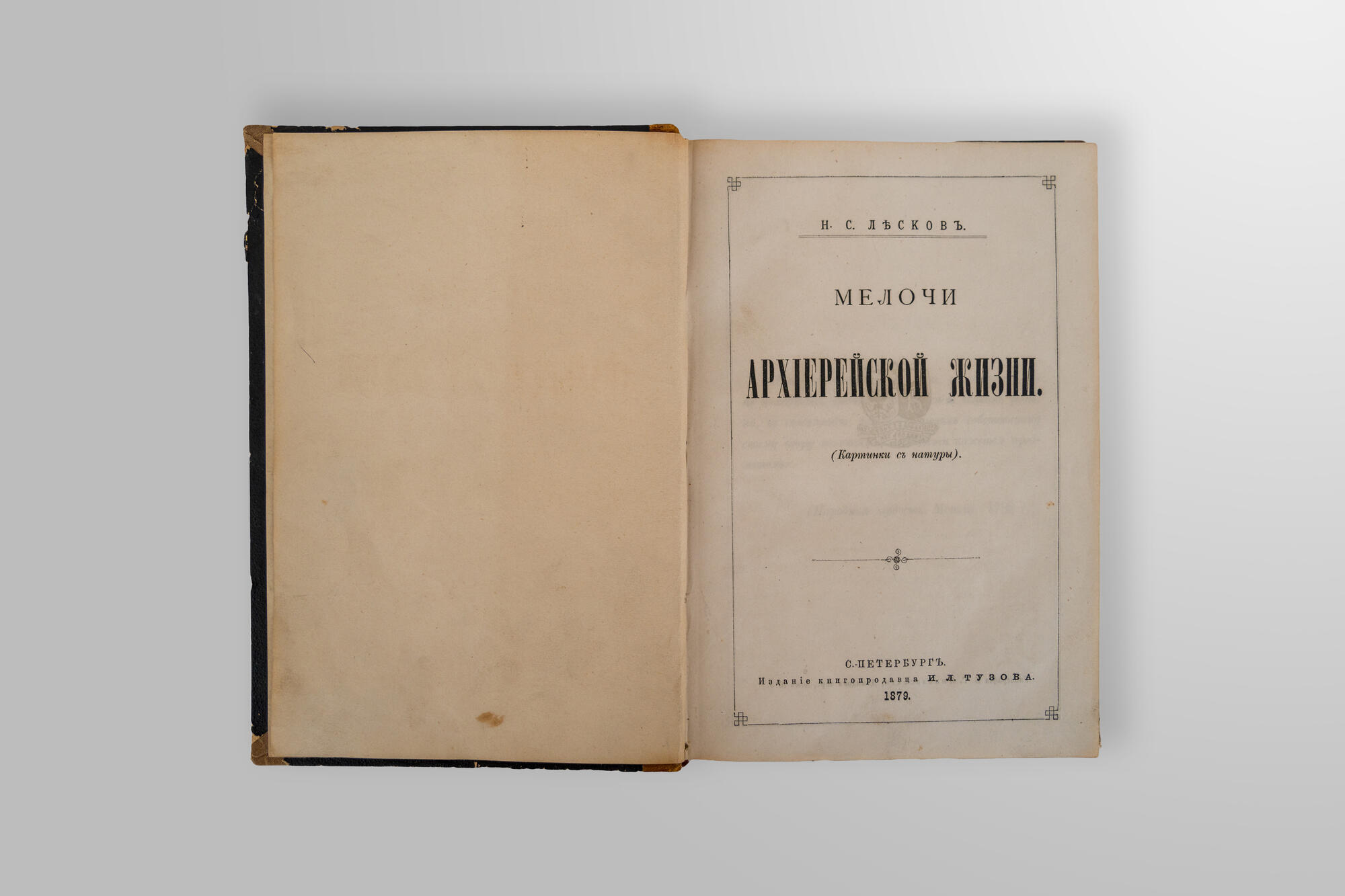

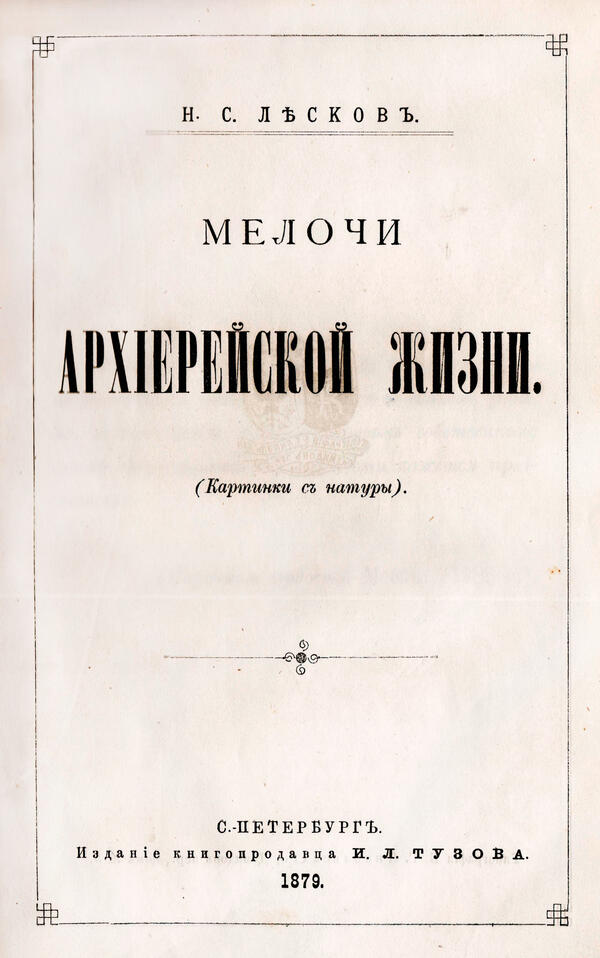

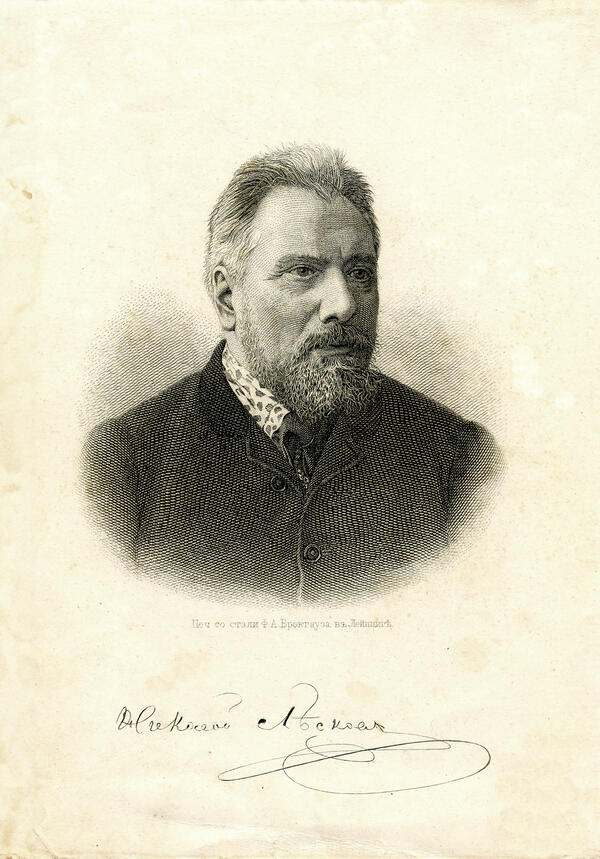

Between September and November 1878, the Novosti (“The News”) newspaper debuted Nikolai Leskov’s “Trifles from the Life of Archbishops”. The complete essays were published in 1879 and were criticized as “a pasquil” and “an audacious pamphlet”.

The writer himself claimed that he did not aim to ridicule the clergy. As his grandparents and great-grandparents were priests and his father was a seminary graduate, Nikolai Leskov had a deep understanding of clergymen with their thoughts, joys, and sorrows.

Still, Leskov was more attracted to the “non-political” aspect of church life. In the 1850s, attending lectures at Kiev University, he got to know many Old Believers whom he considered true representatives of “spiritual Christianity”. He also respected Protestantism and the European Enlightenment.

Irina Gnyusova believes that Leskov’s works about the clergy were influenced by “the traditions of contemporary English literature”, including George Eliot and Anthony Trollope.

The image of the clergy in Russian culture had been subjected to ridicule long before Leskov. It had even been joked about in Russian folk tales. Alexander Rozov noted that this attitude towards the Orthodox clergy began to develop in secular society during the reign of Peter the Great.

Readers were outraged by the way the issue was presented. The Slavophile Ivan Aksakov accused Nikolai Leskov of “turning the Muse… into a kitchen maid” and, while admitting the need for exposure, gave him a piece of advice, quoting a popular song, “You should have said the same but in a different way.”

At the same time, Leskov was also the first Russian writer to create the image of a priest as a “thinking, feeling, and suffering” person. Through anecdotes and sometimes harsh satire, he expressed deep sympathy for people of the most isolated class and described ambiguous characters — stories about rude and unscrupulous bishops alternate with ones about kind and considerate pastors. According to Irina Gnyusova, the writer aimed not to ridicule the clergy, but “to establish a free dialogue between the clergy and society.”

Despite this, the book did not achieve recognition

during the author’s lifetime. Leskov was unable to include it in his collected

works: in 1893, the books were confiscated and burned. Only eight complete

copies of the book were sent to the censorship committee in St Petersburg; one

later ended up in the Public Library, while the rest found their way into

several private collections.