The indigenous small peoples of the North used homemade birch bark containers — boxes, bodies, vessels — to store various household items. These boxes could vary in size and shape — they could be round, oval, rectangular, with overhead flat or convex lids. They were used to store tools, clothes, dishes, and food.

Such light and durable items were also common among the Khanty, the Ugric people living in the north of Western Siberia. The Khanty led a semi-sedentary lifestyle, and their main sources of food were reindeer husbandry and fishing. They often had to travel from place to place and when seasons changed, they moved from winter camps to summer ones and vice versa.

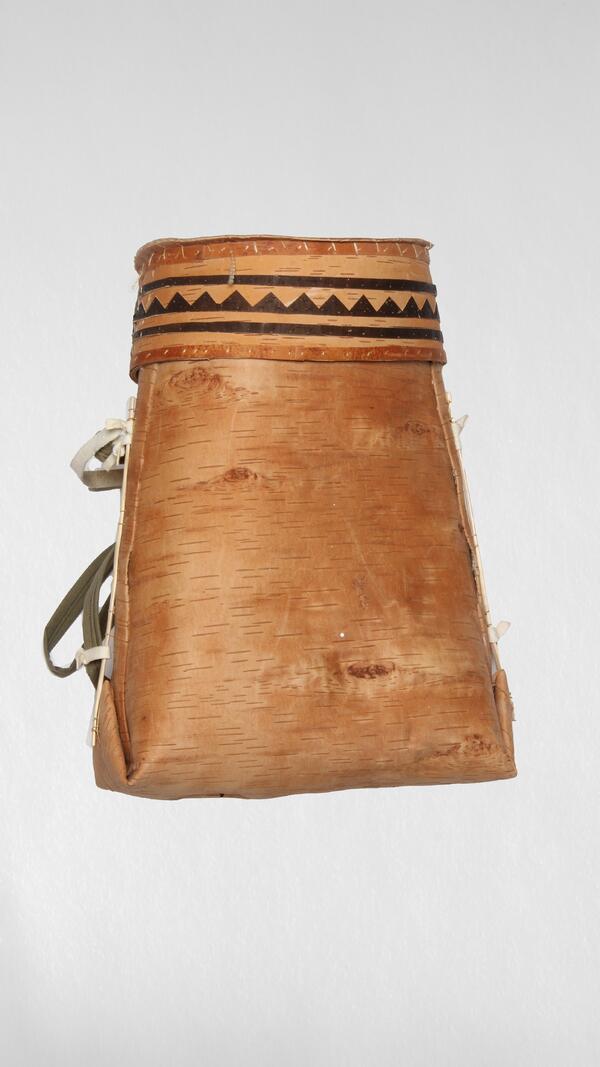

The Khanty used large rectangular or trapezoidal shoulder baskets to carry relatively light-weight loads. They were convenient when carrying fish, berries, meat and other luggage. Large boxes and baskets were also used to store food.

In addition to large shoulder baskets, there were small ones. The Khanty used them for collecting berries. Boxes for low-growing berries were hung from a belt and fastened with a bone or a piece of wood. And if tall-growing berries were picked, the basket as hung around the neck with a strap.

The shoulder basket from the Muravlenko museum collection was made by the craftswoman Fyokla Bondarenko in 2012. She made the container from a long strip of birch bark, which she folded across. She folded the bottom corners into the form of an envelope and clipped them to the sides.

The flat round lid is also made of birch bark. To make it more durable, the craftswoman stitched it with a cedar root and strengthened it with a bird cherry twig. And on top she sewed a dark smoked birch bark and thus created a pattern.

The strap is made of tarpaulin; it is attached to the sides with the help of reindeer “rovduga” — a hide that is similar in properties to suede. To get it, the skin of the deer is first grounded — the subcutaneous tissue is scraped off — then the fur is removed and impregnated with various substances in order to loosen it and prevent collagen from sticking in the fibers. Only after that, the skin is crumpled and dried, and in winter it is frozen. At the last stage of making a “rovduga”, the skin is treated with the smoke of smoldering rotten wood and coals. This is how it gets its color and becomes waterproof.

Such light and durable items were also common among the Khanty, the Ugric people living in the north of Western Siberia. The Khanty led a semi-sedentary lifestyle, and their main sources of food were reindeer husbandry and fishing. They often had to travel from place to place and when seasons changed, they moved from winter camps to summer ones and vice versa.

The Khanty used large rectangular or trapezoidal shoulder baskets to carry relatively light-weight loads. They were convenient when carrying fish, berries, meat and other luggage. Large boxes and baskets were also used to store food.

In addition to large shoulder baskets, there were small ones. The Khanty used them for collecting berries. Boxes for low-growing berries were hung from a belt and fastened with a bone or a piece of wood. And if tall-growing berries were picked, the basket as hung around the neck with a strap.

The shoulder basket from the Muravlenko museum collection was made by the craftswoman Fyokla Bondarenko in 2012. She made the container from a long strip of birch bark, which she folded across. She folded the bottom corners into the form of an envelope and clipped them to the sides.

The flat round lid is also made of birch bark. To make it more durable, the craftswoman stitched it with a cedar root and strengthened it with a bird cherry twig. And on top she sewed a dark smoked birch bark and thus created a pattern.

The strap is made of tarpaulin; it is attached to the sides with the help of reindeer “rovduga” — a hide that is similar in properties to suede. To get it, the skin of the deer is first grounded — the subcutaneous tissue is scraped off — then the fur is removed and impregnated with various substances in order to loosen it and prevent collagen from sticking in the fibers. Only after that, the skin is crumpled and dried, and in winter it is frozen. At the last stage of making a “rovduga”, the skin is treated with the smoke of smoldering rotten wood and coals. This is how it gets its color and becomes waterproof.