From a young age, Sergei Eisenstein was fond of Japanese culture. He began to learn Japanese with his fellow military construction workers during the Civil War. In 1920, he took discharge to Moscow, the eastern branch of the General Staff Academy, hoping to eventually come to Japan as a translator and see the performances of Noh and Kabuki theaters. However, two months later, Sergei Eisenstein went to work at the theater as a stage designer and director and four years later staged his first film Strike, and a year after he gained worldwide fame with the film Battleship Potemkin.

In 1928, Kabuki Theater came on tour to Moscow, and Eisenstein’s dream came true. He saw the performances of the Japanese theater with his own eyes, made friends with its leading actors and amazed them with his knowledge and understanding of their traditions. Eisenstein studied KabUki with books and engravings by Japanese artists, many of whom were ardent theatergoers. One of those artists was ToshusAi SharAku (mid-to-late 18th century - early 19th century), the author of an impressive portrait gallery of actors and sumo wrestlers of that time. Eisenstein deeply appreciated his skills and called him the “Japanese Daumier” /do’mje/ for his acute characteristics, his caustic humor, and ability to convey movement in statics.

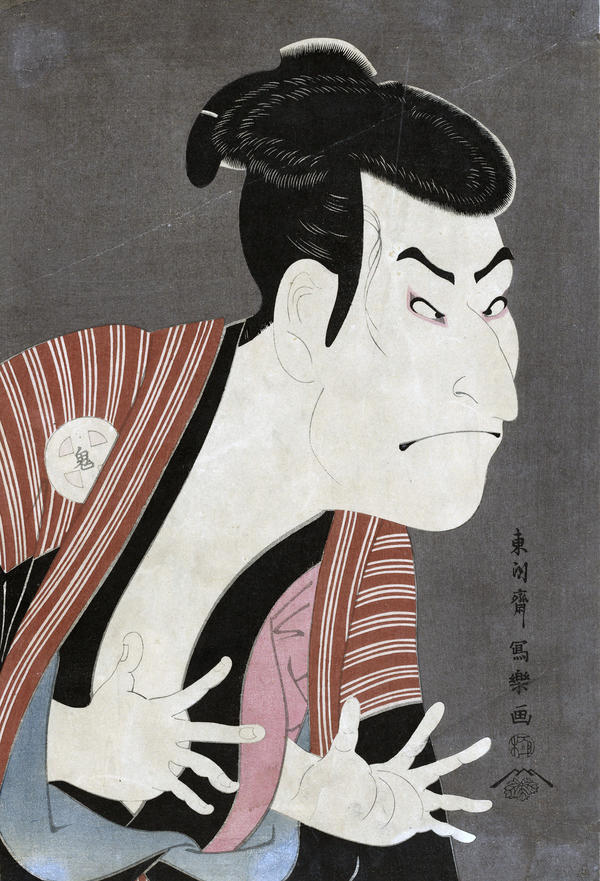

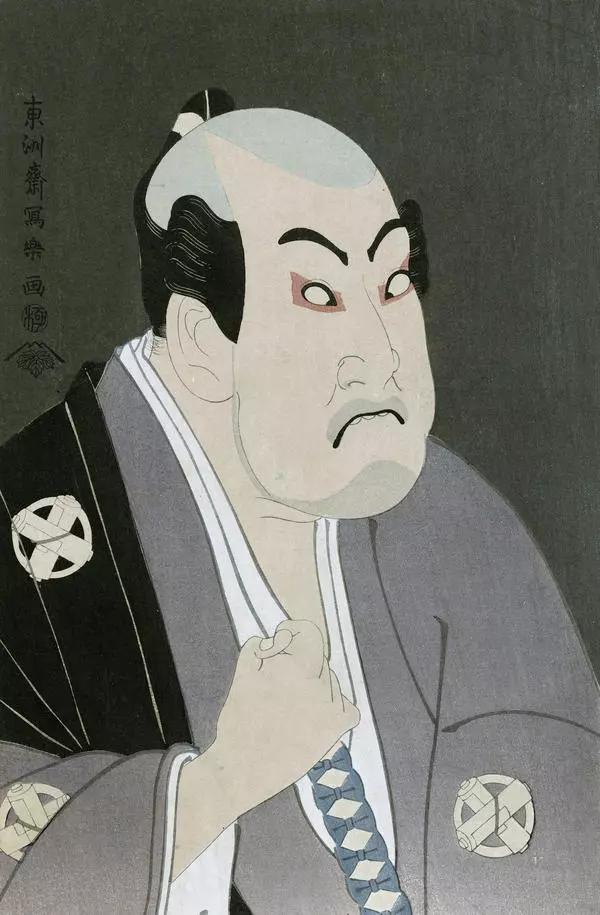

The director managed to buy two portraits by Sharaku. Today they are considered to re-engravings of the 20th century and are kept in the PUshkin State Museum of Fine Arts. The Film Museum displays facsimile (exact) copies of these works. The original color engraving The Actor Otani Oniji as Yakko Edobei is known since 1794 and is one of the most famous works by Sharaku.

Sergei Eisenstein wondered why OtAni’s eyes were crossed that much. The actor wasn’t squint-eyed from birth. It was some kind of convention of play. Kabuki actors were bringing their pupils to the nose bridge in the same way when he saw performances brought to Moscow. This happened at the moments when the actor conveyed a strong emotion, such as anger, with facial gesture. Eisenstein began to study the movement of the eye muscles in various emotions. It turned out that people unknowingly bring the pupils closer when they are fully focused on something or someone, when they are stressed. The Japanese noticed this and put it in the acting rules, so that the audience could see it far away from the stage, and Sharaku focused on this moment in the engraving with grotesque sharpness. This observation helped Eisenstein when he was working with the actors in Ivan the Terrible. He advised the actor Mikhail Kuznetsov to convey the cruelty of oprichniks (life-guardsmen) without growling, but rather just bringing the pupils closer together and the viewer will intuitively understand the character’s state of mind.

In 1928, Kabuki Theater came on tour to Moscow, and Eisenstein’s dream came true. He saw the performances of the Japanese theater with his own eyes, made friends with its leading actors and amazed them with his knowledge and understanding of their traditions. Eisenstein studied KabUki with books and engravings by Japanese artists, many of whom were ardent theatergoers. One of those artists was ToshusAi SharAku (mid-to-late 18th century - early 19th century), the author of an impressive portrait gallery of actors and sumo wrestlers of that time. Eisenstein deeply appreciated his skills and called him the “Japanese Daumier” /do’mje/ for his acute characteristics, his caustic humor, and ability to convey movement in statics.

The director managed to buy two portraits by Sharaku. Today they are considered to re-engravings of the 20th century and are kept in the PUshkin State Museum of Fine Arts. The Film Museum displays facsimile (exact) copies of these works. The original color engraving The Actor Otani Oniji as Yakko Edobei is known since 1794 and is one of the most famous works by Sharaku.

Sergei Eisenstein wondered why OtAni’s eyes were crossed that much. The actor wasn’t squint-eyed from birth. It was some kind of convention of play. Kabuki actors were bringing their pupils to the nose bridge in the same way when he saw performances brought to Moscow. This happened at the moments when the actor conveyed a strong emotion, such as anger, with facial gesture. Eisenstein began to study the movement of the eye muscles in various emotions. It turned out that people unknowingly bring the pupils closer when they are fully focused on something or someone, when they are stressed. The Japanese noticed this and put it in the acting rules, so that the audience could see it far away from the stage, and Sharaku focused on this moment in the engraving with grotesque sharpness. This observation helped Eisenstein when he was working with the actors in Ivan the Terrible. He advised the actor Mikhail Kuznetsov to convey the cruelty of oprichniks (life-guardsmen) without growling, but rather just bringing the pupils closer together and the viewer will intuitively understand the character’s state of mind.