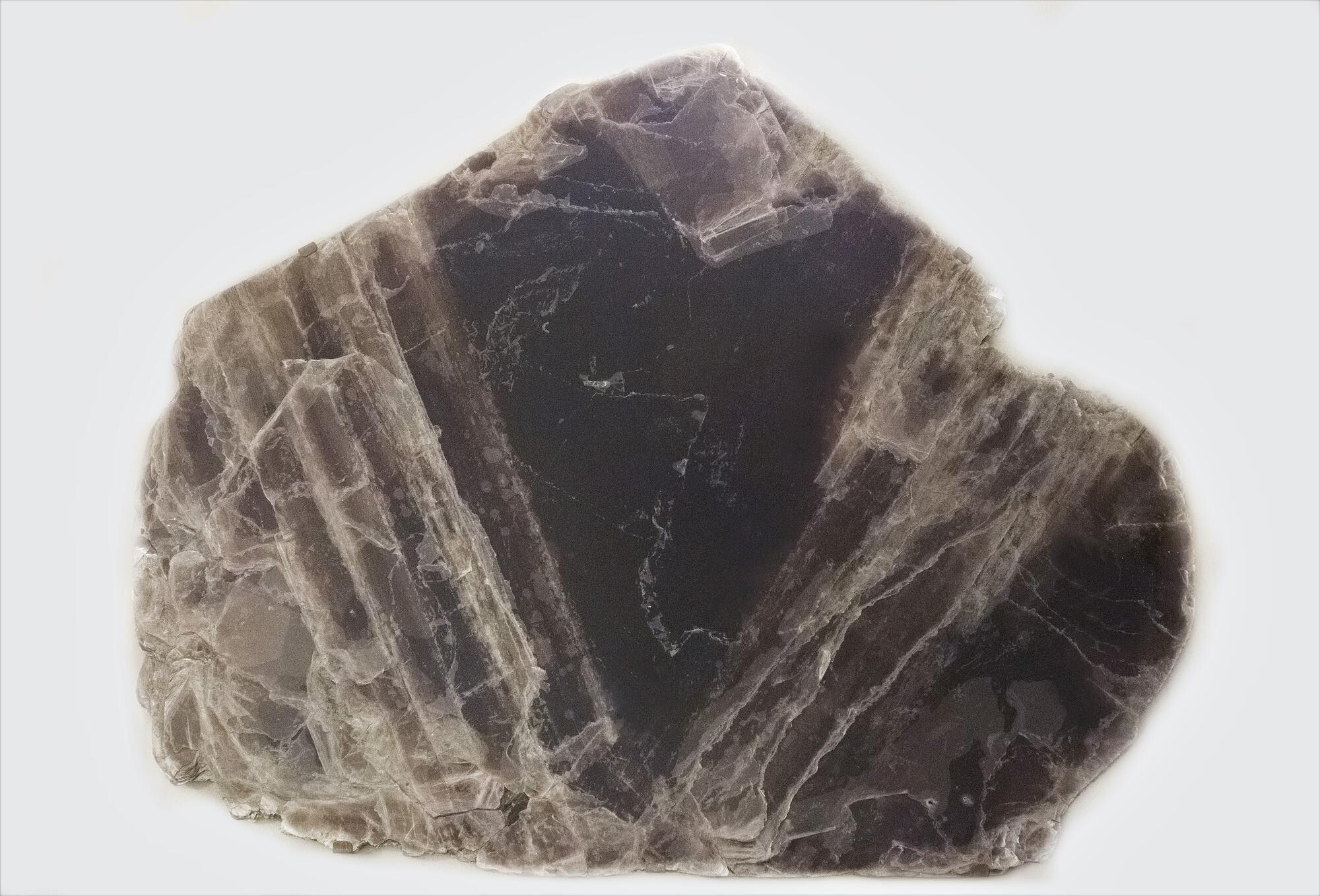

Muscovite, or mica, is one of the minerals found in granite. Back in the middle of the 16th century, Novgorod merchants discovered special solids in the rocks on the western coast of the White Sea, which were given the name “mica” or a layered, glass-like substance.

Large sheets of mica were exported from Karelia via Moscow to the countries of Western Europe, where it was called “Moscow glass”, or just muscovite. This word became the official scientific name of the mineral. There are also other names: the Moscow star, potassium mica, white mica, sericite, antonite, leukophyllite. Mica was split into thin transparent plates and used for window openings. Window panes were not manufactured yet. Small fragments were also used — they were sewn together into large panels. The mica was not completely transparent, but it let the sunlight through.

In Soviet times, Karelia became one of the main areas of muscovite mining in the country. Up to 80% of sheet mica was used in electronics, aviation and rocket technology equipment, nuclear propulsion, for manufacturing viewing windows of high-pressure boilers and other vessels, in medical equipment, and in laser devices. Non-sheet muscovite became a raw material for the cement, rubber and paint industry, for the production of tires, plastics, and waterproofing materials.

A mica factory successfully operated in Petrozavodsk in the second half of the 20th century. The smallest parts for the radio and electrical industry were made from the thinnest mica plates. But after the discovery of semiconductors, mica was not needed anymore. Since 1996, the extraction of mica-muscovite in Karelia has stopped due to lack of demand. Now 9.8% of all Federal reserves of this mineral are concentrated in the depths of Karelia.

The National Museum of the Republic of Karelia houses not only samples of muscovite but also finished products, in which this mineral was used. For example, a portable lantern was presumably made by the masters of the Alexander-Svirskiy monastery in the 17th century. At that time, mica, which was mined in the Russian North, was widely used instead of glass.

Large sheets of mica were exported from Karelia via Moscow to the countries of Western Europe, where it was called “Moscow glass”, or just muscovite. This word became the official scientific name of the mineral. There are also other names: the Moscow star, potassium mica, white mica, sericite, antonite, leukophyllite. Mica was split into thin transparent plates and used for window openings. Window panes were not manufactured yet. Small fragments were also used — they were sewn together into large panels. The mica was not completely transparent, but it let the sunlight through.

In Soviet times, Karelia became one of the main areas of muscovite mining in the country. Up to 80% of sheet mica was used in electronics, aviation and rocket technology equipment, nuclear propulsion, for manufacturing viewing windows of high-pressure boilers and other vessels, in medical equipment, and in laser devices. Non-sheet muscovite became a raw material for the cement, rubber and paint industry, for the production of tires, plastics, and waterproofing materials.

A mica factory successfully operated in Petrozavodsk in the second half of the 20th century. The smallest parts for the radio and electrical industry were made from the thinnest mica plates. But after the discovery of semiconductors, mica was not needed anymore. Since 1996, the extraction of mica-muscovite in Karelia has stopped due to lack of demand. Now 9.8% of all Federal reserves of this mineral are concentrated in the depths of Karelia.

The National Museum of the Republic of Karelia houses not only samples of muscovite but also finished products, in which this mineral was used. For example, a portable lantern was presumably made by the masters of the Alexander-Svirskiy monastery in the 17th century. At that time, mica, which was mined in the Russian North, was widely used instead of glass.