Klavdia Kozlova’s painting Female portrait belongs to the mature period of the artist’s work, when she had already left behind experiments with expressionism, ‘aesthetic formalism’ advocated by Easel Painters Association, as well as had broken away from the ‘Art Brigade’, who had set the trend for socialist realism.

On the canvas, we see a woman sitting in a simple white dress. The woman’s head is a little turned, her arms are down along the body. You cannot tell the woman is relaxed, her face doesn’t look serene, too. On the contrary, the painting looks as if it is soaked in static tension. On the right from the woman there is a table with a white tablecloth. On the tablecloth sits a jug, flowers and fruits adding up to an academically looking still life.

In spite of the ordinariness of the composition, there is nothing accidental in the picture. The annoyingly artificial, staged composition on the table is a game of symbols. The white wedding dress, tablecloth, and the vessel, flower and fruit on it are the embodiment of the feminine principle. And the tense female figure in a dress that lacks romantic wedding whiteness, is holding her head in the shadow of a bush, sadly looking aside. The rejection can also be read in the body position on the portrait, she is detaching herself away from the table, as if rejecting all these feminine signs.

Klavdiya Kozlova studied at the Moscow VKHUTEMAS (Higher Art and Technical Studios), after graduating she joined the Easel Painters Association, formed under the leadership of David Stenberg. The Easel Painters opposed the artistic association called AHRR — the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. The latter actively fought against ‘formalism’, developing traditions of the Russian avant-garde. The Easel Painters, on the contrary, who had broken away from the Itinerants and were following the avant-gardists, tended to be realistic in painting, and widely used techniques of European expressionism.

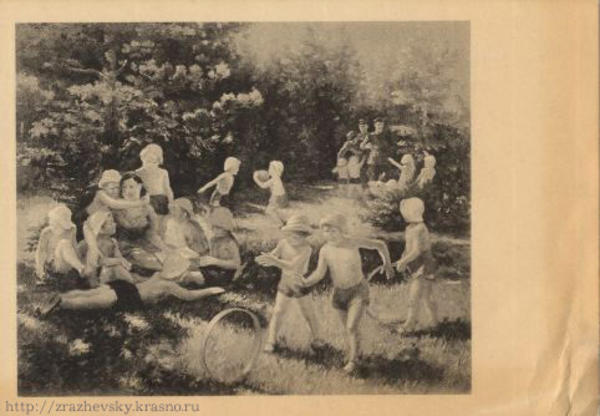

Kozlova’s creative work deeply absorbed the canon of the Easel Painters Association. On the whole, she stuck to the guidelines of society, avoiding military and revolutionary themes, looking for “signs of time”, sought to capture life in bright and peaceful subjects. Such as Children of the Commanding Staff in the Summer Colony, Nursery at a Farm and Change of Motorists in the Mine.

On the canvas, we see a woman sitting in a simple white dress. The woman’s head is a little turned, her arms are down along the body. You cannot tell the woman is relaxed, her face doesn’t look serene, too. On the contrary, the painting looks as if it is soaked in static tension. On the right from the woman there is a table with a white tablecloth. On the tablecloth sits a jug, flowers and fruits adding up to an academically looking still life.

In spite of the ordinariness of the composition, there is nothing accidental in the picture. The annoyingly artificial, staged composition on the table is a game of symbols. The white wedding dress, tablecloth, and the vessel, flower and fruit on it are the embodiment of the feminine principle. And the tense female figure in a dress that lacks romantic wedding whiteness, is holding her head in the shadow of a bush, sadly looking aside. The rejection can also be read in the body position on the portrait, she is detaching herself away from the table, as if rejecting all these feminine signs.

Klavdiya Kozlova studied at the Moscow VKHUTEMAS (Higher Art and Technical Studios), after graduating she joined the Easel Painters Association, formed under the leadership of David Stenberg. The Easel Painters opposed the artistic association called AHRR — the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia. The latter actively fought against ‘formalism’, developing traditions of the Russian avant-garde. The Easel Painters, on the contrary, who had broken away from the Itinerants and were following the avant-gardists, tended to be realistic in painting, and widely used techniques of European expressionism.

Kozlova’s creative work deeply absorbed the canon of the Easel Painters Association. On the whole, she stuck to the guidelines of society, avoiding military and revolutionary themes, looking for “signs of time”, sought to capture life in bright and peaceful subjects. Such as Children of the Commanding Staff in the Summer Colony, Nursery at a Farm and Change of Motorists in the Mine.