In the 1970s, archaeologist Vladimir Gening found the first burial with the remains of a chariot at the Sintashta burial ground in the southern Chelyabinsk Region. Over the next 40 years, about 25 similar burials were discovered. The oldest burial dates back to 2026 BC and was discovered at the Krivoye Ozero (literally: Curved Lake) burial ground in the Troitsky District of the Chelyabinsk Region.

We know how the tack of chariot horses looked like thanks to the discovered corneous cheekpieces and bridle strap guiding pieces, as well as bone or corneous ‘spatulas’ — imitation feather tassels that adorned the heads of horses. Of special importance are the burials containing ‘chariot units, ’ which contain elements of horse tack, namely bit shanks, and often the remains of carts as well. The subtleties of the funeral rites related to chariot warriors are not fully understood. We can only assume that chariots or their parts were placed in the graves to deliver the deceased to the land of the dead.

Typically, it is only imprints or poorly preserved wooden wheel parts, like rims, spokes, hubs, and leather tires, that have survived to the present day. The size of the chariot is determined by the dimensions of the grave pit and the distance between the wheels. To make the chariot body more stable, wheels were placed in wheel pits—paired lenticular depressions at the bottom of the grave—by a third or a quarter of their diameter. The chariot could be buried intact or in a disassembled state. Sometimes only the axle and wheels were placed next to the deceased. However, whole chariot units are often found in burial pits, including carts, horse tack parts (bit shanks), and chariot warrior weapons. Sacrificial horses were also often buried next to the deceased.

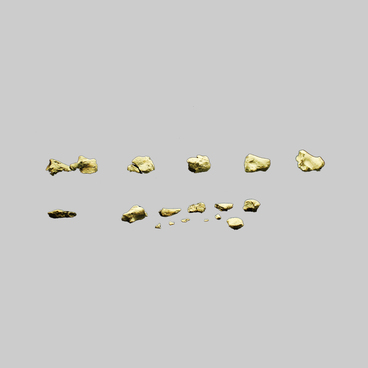

Bit shanks are metal or bone parts of a horse tack that connect the reins to the bridle. Riders used them to give commands to the horses: when they pulled on the reins, the shank pressed on the muzzle and forced the animal to turn, stop, or perform some other action. They were shaped like rings, spoked wheels, or rods with fasteners at the ends. Archaeologists usually find ring-shaped shanks among the grave goods. However, the tack elements on display at the State Museum of the South Ural History have a different shape: segmented, with solid spikes. They were hand-crafted from elk antlers. The shank’s body has a trapezoid shape. The hooks that fix the belt look in opposite directions.

The process involved in the making of a shank body was rather unusual: it was thinned both on the outside and on the inside, and its inner part was processed after the central hole had been punched (or at least outlined). The craftsman made the shank body smooth on the outside and wavy on the inside, emphasizing the upper spikes and lengthening them.

We know how the tack of chariot horses looked like thanks to the discovered corneous cheekpieces and bridle strap guiding pieces, as well as bone or corneous ‘spatulas’ — imitation feather tassels that adorned the heads of horses. Of special importance are the burials containing ‘chariot units, ’ which contain elements of horse tack, namely bit shanks, and often the remains of carts as well. The subtleties of the funeral rites related to chariot warriors are not fully understood. We can only assume that chariots or their parts were placed in the graves to deliver the deceased to the land of the dead.

Typically, it is only imprints or poorly preserved wooden wheel parts, like rims, spokes, hubs, and leather tires, that have survived to the present day. The size of the chariot is determined by the dimensions of the grave pit and the distance between the wheels. To make the chariot body more stable, wheels were placed in wheel pits—paired lenticular depressions at the bottom of the grave—by a third or a quarter of their diameter. The chariot could be buried intact or in a disassembled state. Sometimes only the axle and wheels were placed next to the deceased. However, whole chariot units are often found in burial pits, including carts, horse tack parts (bit shanks), and chariot warrior weapons. Sacrificial horses were also often buried next to the deceased.

Bit shanks are metal or bone parts of a horse tack that connect the reins to the bridle. Riders used them to give commands to the horses: when they pulled on the reins, the shank pressed on the muzzle and forced the animal to turn, stop, or perform some other action. They were shaped like rings, spoked wheels, or rods with fasteners at the ends. Archaeologists usually find ring-shaped shanks among the grave goods. However, the tack elements on display at the State Museum of the South Ural History have a different shape: segmented, with solid spikes. They were hand-crafted from elk antlers. The shank’s body has a trapezoid shape. The hooks that fix the belt look in opposite directions.

The process involved in the making of a shank body was rather unusual: it was thinned both on the outside and on the inside, and its inner part was processed after the central hole had been punched (or at least outlined). The craftsman made the shank body smooth on the outside and wavy on the inside, emphasizing the upper spikes and lengthening them.