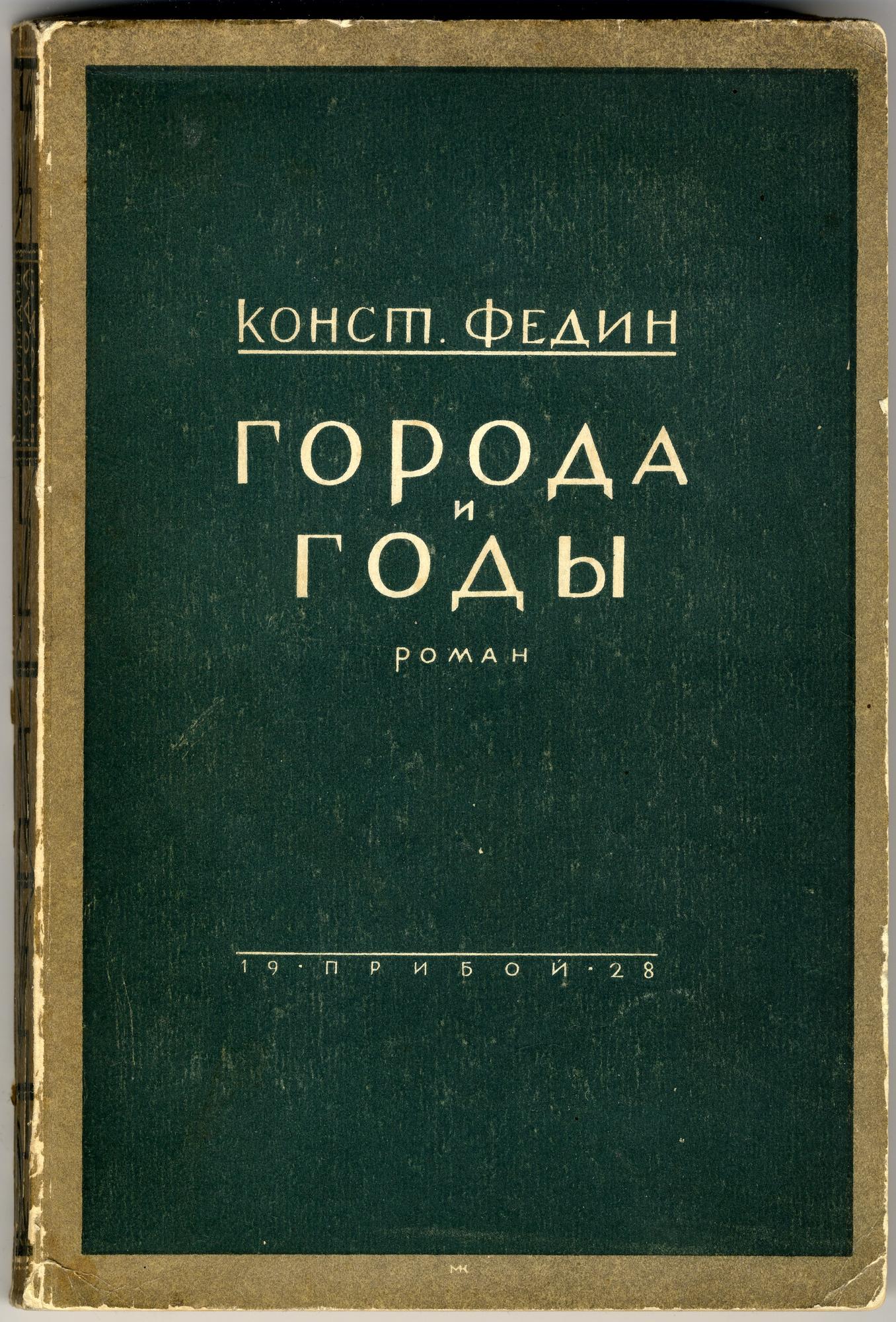

Fedin’s novel Cities and Years came out as a separate publication at the end of 1924 and instantly made the young author one of the most prominent Russian writers at the time. The novel was widely discussed in writers’ circles, attracted scores of letters from readers, was studied in schools, and attracted the attention of the biggest theatre and movie directors. The work soon brought Fedin fame across Europe. The novel was the first real attempt to make sense of the Russian Revolution, the First World War and the Civil War in an artistic light and present two great countries, Russia and Germany, at a historical crossroads.

The release of the novel gave rise to heated discussion in the Soviet and foreign press. The book’s main character, an artist called Andrei Startsov, is a partially autobiographical figure. The action of the book is divided between Russia and Germany before and after the Revolution. Russian émigré critics unanimously praised the book, lauding its humanism and linking it with the best traditions of Russian classical literature. They also considered its treatment of the intellectual main character a virtue. Many Soviet critics, however, while recognizing the high artistic merits of the work, directed some serious accusations at the author, accusing him of misunderstanding and distorting the Revolution.

They did not spare any epithets for the main character Andrei Startsov, either, calling him a teary-eyed intellectual of the old regime, a blood relative of the characters of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard and Three Sisters, a living corpse, ‘which rots and stinks before the eyes of the reader.’ For many years, the criteria presented by the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers for the approach to be taken by Soviet critics to the novel remained unchanged. Only in recent years has there been an attempt to objectively evaluate its role in the history of Russian literature. Writers such as Maxim Gorky, Boris Pasternak, Ivan Sokolov-Mikitov, Boris Pilnyak, Vladislav Khodasevich and Stefan Zweig were full of praise for Fedin’s first novel. A new edition of the book was published every year in the Soviet Union until 1937, making 14 editions in total, before it was removed from all publishing plans for 20 years. The book returned to print in 1957 and has been published regularly since then. It is just as relevant now for readers as it was when it was first published.

The release of the novel gave rise to heated discussion in the Soviet and foreign press. The book’s main character, an artist called Andrei Startsov, is a partially autobiographical figure. The action of the book is divided between Russia and Germany before and after the Revolution. Russian émigré critics unanimously praised the book, lauding its humanism and linking it with the best traditions of Russian classical literature. They also considered its treatment of the intellectual main character a virtue. Many Soviet critics, however, while recognizing the high artistic merits of the work, directed some serious accusations at the author, accusing him of misunderstanding and distorting the Revolution.

They did not spare any epithets for the main character Andrei Startsov, either, calling him a teary-eyed intellectual of the old regime, a blood relative of the characters of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard and Three Sisters, a living corpse, ‘which rots and stinks before the eyes of the reader.’ For many years, the criteria presented by the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers for the approach to be taken by Soviet critics to the novel remained unchanged. Only in recent years has there been an attempt to objectively evaluate its role in the history of Russian literature. Writers such as Maxim Gorky, Boris Pasternak, Ivan Sokolov-Mikitov, Boris Pilnyak, Vladislav Khodasevich and Stefan Zweig were full of praise for Fedin’s first novel. A new edition of the book was published every year in the Soviet Union until 1937, making 14 editions in total, before it was removed from all publishing plans for 20 years. The book returned to print in 1957 and has been published regularly since then. It is just as relevant now for readers as it was when it was first published.