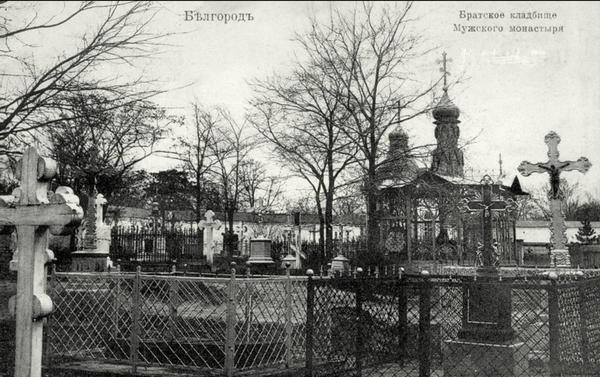

Postcards with views of the Holy Trinity Monastery became especially popular after 1911, the year of the canonization of Saint Joasaph. These are not only images directly related to the memory of the saint (his chamber and reliquary) but also photographs of individual monastery churches and a fraternal cemetery — the first Belgorod necropolis.

The exact time when the cemetery arose is not known. The dates on the discovered tombstones indicate that it existed long before the foundation of the monastery, but was later attributed to it and enclosed by the monastery fence. It was mostly intended for the priesthood: monks, metropolitans, and bishops of the monastery, as well as seminary teachers.

The local history expert Alexander Nikolayevich Krupenkov pointed out that the earliest of the Holy Trinity burials known today is that of Bishop of Belgorod and Oboyan Epiphanius Tikhorsky, the organizer of a school for the clergy’s children and the Kharkiv Collegium, an educational institution for students from all orders of society. He died in 1731.

Hieromonk Veniamin, revered in Belgorod, who had served in the Black Sea Fleet, taken part in the Battle of Sinop and the siege of Sevastopol, and been awarded the Order of Saint Anna (3rd degree) for courage, was buried there. The cemetery accommodated the burial places of priests executed by the Bolsheviks, including protopriest Pyotr Vasilyevich Sionsky, the superintendent of the Belgorod Theological School, and Bishop Nikodim (Kononov), who was arrested for preaching against plunder and violence and was canonized in 2000.

At the same time, during the excavations, numerous graves of secular persons — doctors, military personnel, merchants, scientists, and other honorary citizens — were discovered. One of the first secular burials is that of a merchant known only as Vadim (his last name being illegible). Obviously, to be buried within the frame of the monastery was considered a great honor.

After the demolition of the monastery ensemble in 1923, the only landmarks for the approximate location of the necropolis were the houses along Bogdan Khmelnitsky Avenue and Holy Trinity Boulevard as well as part of the wasteland nicknamed by the locals as “The Fields of Miracles”. Although all the buildings that rose above the ground had been demolished, the foundation of the monastery with the tomb (“cave”) of Saint Joasaph and the crypt of hieromartyr Bishop Nikodim (Kononov) was undisturbed.

The exact time when the cemetery arose is not known. The dates on the discovered tombstones indicate that it existed long before the foundation of the monastery, but was later attributed to it and enclosed by the monastery fence. It was mostly intended for the priesthood: monks, metropolitans, and bishops of the monastery, as well as seminary teachers.

The local history expert Alexander Nikolayevich Krupenkov pointed out that the earliest of the Holy Trinity burials known today is that of Bishop of Belgorod and Oboyan Epiphanius Tikhorsky, the organizer of a school for the clergy’s children and the Kharkiv Collegium, an educational institution for students from all orders of society. He died in 1731.

Hieromonk Veniamin, revered in Belgorod, who had served in the Black Sea Fleet, taken part in the Battle of Sinop and the siege of Sevastopol, and been awarded the Order of Saint Anna (3rd degree) for courage, was buried there. The cemetery accommodated the burial places of priests executed by the Bolsheviks, including protopriest Pyotr Vasilyevich Sionsky, the superintendent of the Belgorod Theological School, and Bishop Nikodim (Kononov), who was arrested for preaching against plunder and violence and was canonized in 2000.

At the same time, during the excavations, numerous graves of secular persons — doctors, military personnel, merchants, scientists, and other honorary citizens — were discovered. One of the first secular burials is that of a merchant known only as Vadim (his last name being illegible). Obviously, to be buried within the frame of the monastery was considered a great honor.

After the demolition of the monastery ensemble in 1923, the only landmarks for the approximate location of the necropolis were the houses along Bogdan Khmelnitsky Avenue and Holy Trinity Boulevard as well as part of the wasteland nicknamed by the locals as “The Fields of Miracles”. Although all the buildings that rose above the ground had been demolished, the foundation of the monastery with the tomb (“cave”) of Saint Joasaph and the crypt of hieromartyr Bishop Nikodim (Kononov) was undisturbed.