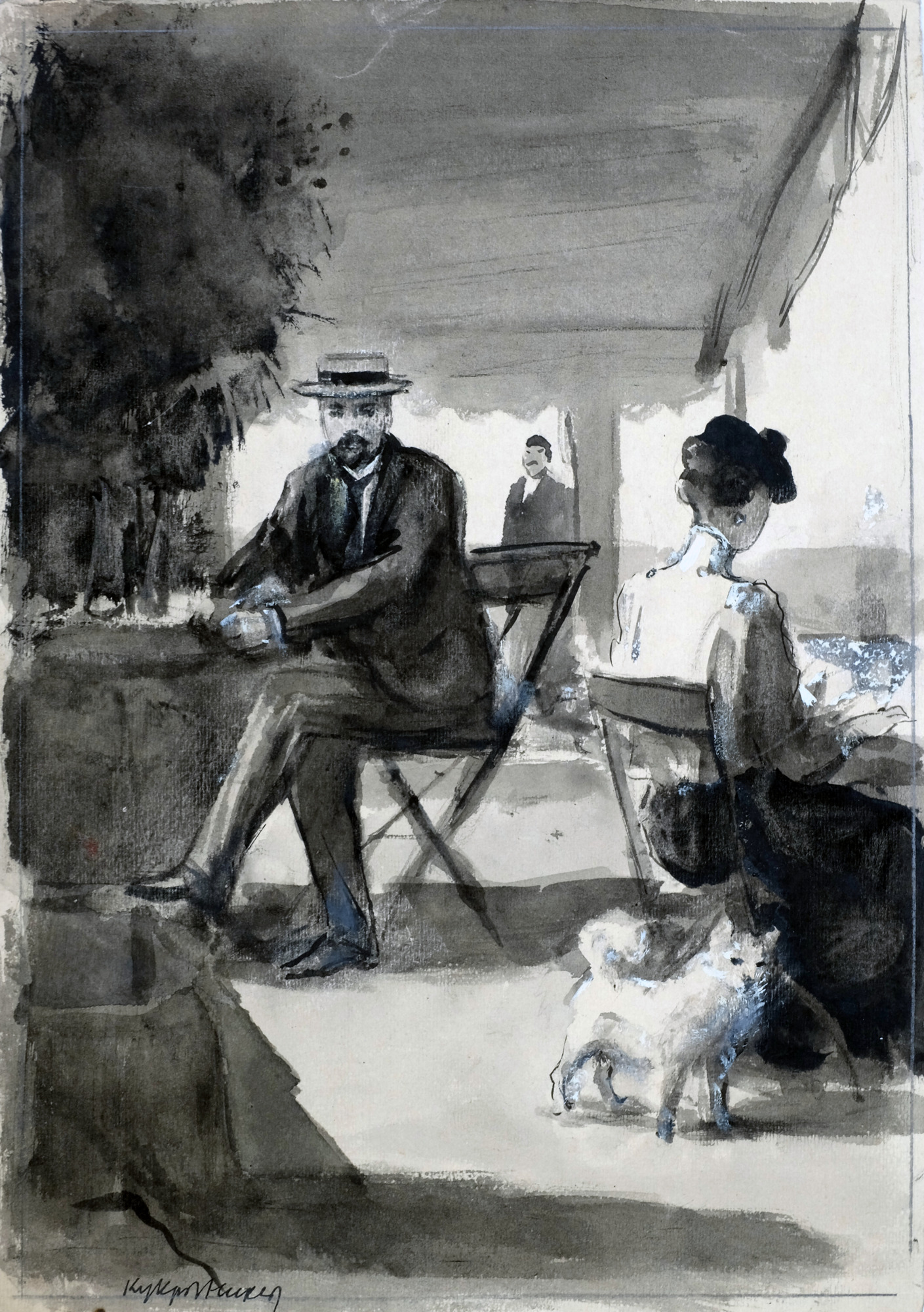

Under the glass are the illustrations for Anton Pavlovich Chekhov’s story ‘The Lady with the Dog’, written in 1899 in the writer’s office, located on the second floor of the Yalta mansion. Anton Pavlovich transferred his favorite places into the story: the Yalta embankment, Oreanda Park, places outside the city.

From the spring of 1899 until the beginning of the next year, Chekhov experienced probably the most joyful moments of Yalta life. During this period, he moved to Crimea and set up his own home, he worked with inspiration; “The Seagull” and “Uncle Vanya” had a success on the stage of the Moscow Art Theater; the theater troupe visited and staged these plays in Yalta especially for the author. Chekhov received honorary membership in the Academy of Sciences. And, more importantly, personal happiness. These joyful events gave vigor and brightened up the forced move to “warm Siberia”, as Chekhov jokingly called Yalta and its surroundings. And he seriously mentioned that he liked the Crimean Peninsula more than the coast of the Riviera.

Familiar to everyone, the abbreviation “Kukryniksy” combined the first syllables of the names of the artists Kupriyanov and Krylov, as well as the first three letters of the name and the initial letter of the surname of their comrade and colleague Nikolai Sokolov. They illustrated Chekhov’s stories in 1940-1941, 1945-1946 and 1953. In total, the Kukryniksy created illustrations for more than 40 humorous, lyrical, sad stories of the writer (‘Surgery’, ‘The Burbot’, ‘Misery’, ‘Betrothed’ and others).

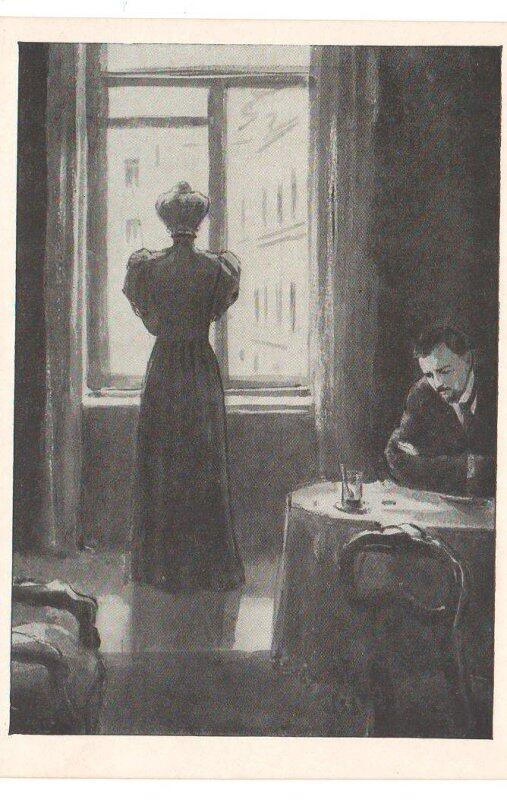

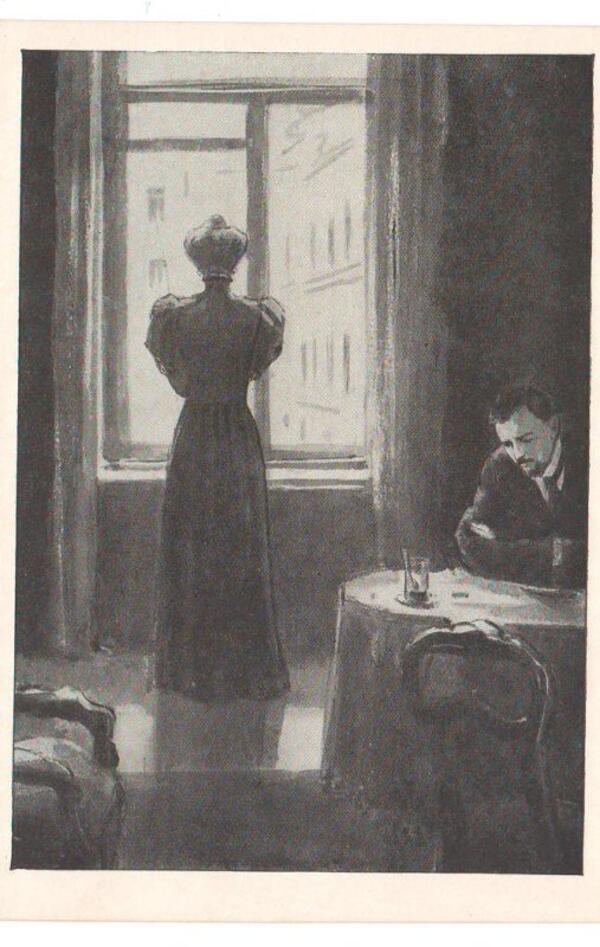

Scenes from ‘The Lady with the Dog’ are painted by artists in black watercolors. These illustrations are made with attention to every stroke, every little thing that surrounded the heroes of the story, which makes their images brighter and more versatile. From 1945 to 1946, the Kukryniksy completed so many drawings for ‘The Lady with the Dog’ that it turned out to be an independent work in pictures, fully revealing not only the plot of the story, but also the psychology of the characters' love story. The background of illustrations changing from bright sunny to blurry twilight and soft transitions of black watercolor on the tonal scale create the illusion of cinematic illustrations. The artists managed to convey Chekhov’s humor graphically, without going beyond the accuracy of the plot and the clarity of the composition.

In the collection of stories “The Lady with the Dog” holds 14 pages, and the Kukryniksy accompanied the work with more than 40 drawings, which, when viewed sequentially, allow you to fully understand the plot of the story without reading. In their illustrations, “The Lady with the Dog” is not only a story of one love, but also a story about a person’s weakness, from which his problems and vices grow.

A decade and a half later, in the 60s of the 20th century, Kukryniksy’s works “came to life” in the film by Joseph Kheifits. Perhaps unconsciously, the members of the film crew repeated the close-ups of the artists, the appearance and costumes of the characters, and camera angles. But the most amazing thing is that the gray-yellow tones of the drawings and the black lines of the watercolor were transferred to the cinema, and in some shots the light emanating from somewhere behind was repeated, as if from the characters’ past.

From the spring of 1899 until the beginning of the next year, Chekhov experienced probably the most joyful moments of Yalta life. During this period, he moved to Crimea and set up his own home, he worked with inspiration; “The Seagull” and “Uncle Vanya” had a success on the stage of the Moscow Art Theater; the theater troupe visited and staged these plays in Yalta especially for the author. Chekhov received honorary membership in the Academy of Sciences. And, more importantly, personal happiness. These joyful events gave vigor and brightened up the forced move to “warm Siberia”, as Chekhov jokingly called Yalta and its surroundings. And he seriously mentioned that he liked the Crimean Peninsula more than the coast of the Riviera.

Familiar to everyone, the abbreviation “Kukryniksy” combined the first syllables of the names of the artists Kupriyanov and Krylov, as well as the first three letters of the name and the initial letter of the surname of their comrade and colleague Nikolai Sokolov. They illustrated Chekhov’s stories in 1940-1941, 1945-1946 and 1953. In total, the Kukryniksy created illustrations for more than 40 humorous, lyrical, sad stories of the writer (‘Surgery’, ‘The Burbot’, ‘Misery’, ‘Betrothed’ and others).

Scenes from ‘The Lady with the Dog’ are painted by artists in black watercolors. These illustrations are made with attention to every stroke, every little thing that surrounded the heroes of the story, which makes their images brighter and more versatile. From 1945 to 1946, the Kukryniksy completed so many drawings for ‘The Lady with the Dog’ that it turned out to be an independent work in pictures, fully revealing not only the plot of the story, but also the psychology of the characters' love story. The background of illustrations changing from bright sunny to blurry twilight and soft transitions of black watercolor on the tonal scale create the illusion of cinematic illustrations. The artists managed to convey Chekhov’s humor graphically, without going beyond the accuracy of the plot and the clarity of the composition.

In the collection of stories “The Lady with the Dog” holds 14 pages, and the Kukryniksy accompanied the work with more than 40 drawings, which, when viewed sequentially, allow you to fully understand the plot of the story without reading. In their illustrations, “The Lady with the Dog” is not only a story of one love, but also a story about a person’s weakness, from which his problems and vices grow.

A decade and a half later, in the 60s of the 20th century, Kukryniksy’s works “came to life” in the film by Joseph Kheifits. Perhaps unconsciously, the members of the film crew repeated the close-ups of the artists, the appearance and costumes of the characters, and camera angles. But the most amazing thing is that the gray-yellow tones of the drawings and the black lines of the watercolor were transferred to the cinema, and in some shots the light emanating from somewhere behind was repeated, as if from the characters’ past.