The production of children’s toys in Tyumen began in the early 20th century. In the 1920s, when the puppeteer artist Ivan Ivanovich Oveshkov came to Tyumen from Tobolsk, wooden toys started to appear in children’s life.

After a while, several of the city’s cooperatives started making children’s toys from sawdust and papier-mâché. But particularly keen attention was paid to them during the Great Patriotic War. In 1943, the Council of People’s Commissars issued a resolution, emphasizing the need to increase the production of toys: every factory or plant was obliged to make them.

Toy cars and dump trucks began to leave the production lines where military equipment was assembled. A commission was created under the regional education committee, where, after several stages of consideration, it was determined which toy could be allowed for sale.

Dolls and other characters were to have beautiful and kind faces, while toy animals were supposed to look affectionate. Thus, even in hard wartime, toys instilled kindness and inspired joy. At the same time, during the war, a plastics plant was established in Tyumen. It began to manufacture toys from celluloid.

It was a new stage that revolutionized children’s games: such toys were water-resistant, and it was at that time that the tradition of bathing with toys emerged. However, in the 1960s, the production of toys made of celluloid was banned across the world: the material ignited easily and, if handled carelessly, could lead to irreversible consequences. Celluloid toys were replaced by toys made from other types of plastic.

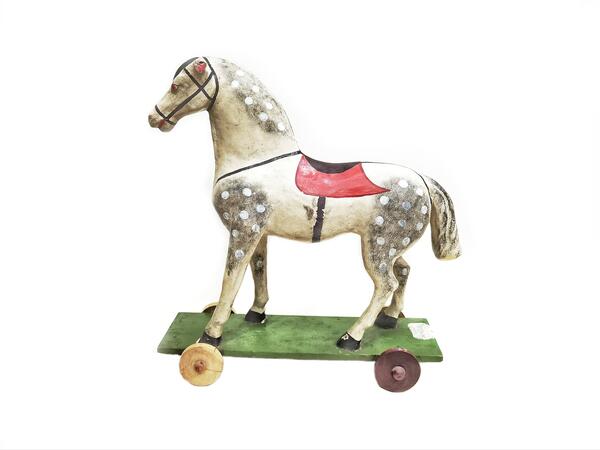

Among the most popular toys were horses: wheeled horses (including those with wheels attached to a stand), rocking horses on special runners, smaller horses made of rubber, celluloid, wood, or plastic, hobby horses in the form of a horse’s head on a stick, racing horses made of metal, harnessed to a two-wheeled cart.

This toy from the museum’s collection — a wooden horse on a stand with wheels — is made of papier-mâché and coated with paints. Later, the production of toys made of plastic and plywood was developed.

After a while, several of the city’s cooperatives started making children’s toys from sawdust and papier-mâché. But particularly keen attention was paid to them during the Great Patriotic War. In 1943, the Council of People’s Commissars issued a resolution, emphasizing the need to increase the production of toys: every factory or plant was obliged to make them.

Toy cars and dump trucks began to leave the production lines where military equipment was assembled. A commission was created under the regional education committee, where, after several stages of consideration, it was determined which toy could be allowed for sale.

Dolls and other characters were to have beautiful and kind faces, while toy animals were supposed to look affectionate. Thus, even in hard wartime, toys instilled kindness and inspired joy. At the same time, during the war, a plastics plant was established in Tyumen. It began to manufacture toys from celluloid.

It was a new stage that revolutionized children’s games: such toys were water-resistant, and it was at that time that the tradition of bathing with toys emerged. However, in the 1960s, the production of toys made of celluloid was banned across the world: the material ignited easily and, if handled carelessly, could lead to irreversible consequences. Celluloid toys were replaced by toys made from other types of plastic.

Among the most popular toys were horses: wheeled horses (including those with wheels attached to a stand), rocking horses on special runners, smaller horses made of rubber, celluloid, wood, or plastic, hobby horses in the form of a horse’s head on a stick, racing horses made of metal, harnessed to a two-wheeled cart.

This toy from the museum’s collection — a wooden horse on a stand with wheels — is made of papier-mâché and coated with paints. Later, the production of toys made of plastic and plywood was developed.