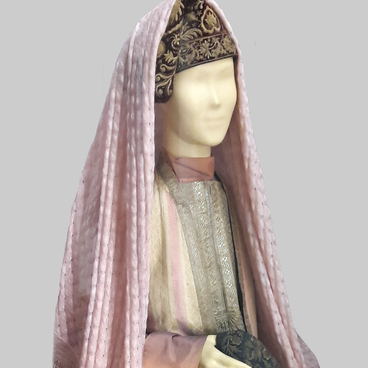

Hushpu — a Chuvash headdress for married women that has a solid, conical or cylindrical frame. The upper edge of the hushpu frame was covered with coral and beads; and below there were silver coins of various denominations, or copper medals and tin plaques were sewn in row, like fish scales. On the back, the headdress had a long tail, which was also decorated with beads, coins, braiding, and copper medals.

In ancient times, the hushpu was a headress that was a must for every married woman, and without it she could not go outside. This was reported by Peter Simon Pallas and all the authors in the 18th and 19th centuries that wrote about the Chuvash, calling it a ‘fushpu’, a ‘kashpal’, a ‘hoshpa’, or a ‘hushpu’. They give very contradictory information about this attire, sometimes describing it as a helmet, or a ‘cap’ without a crown, or saying it has the form of a truncated cone.

The hushpu for married women had different shapes, but almost all of them had an open top, as well as a back part in the form of a straight strip of canvas that descended down to waist level. A hushpu that had a helmet-like shape, with a small hole in its upper part, became widespread among the Pribelsk Chuvash. The frame was made from a dense material, and was covered by rows of beads and coins. The conceptual and decorative center of the headdress was a strip of ornamentation with geometric motifs running along the circumference of the person’s head, along the upper edge of the hushpu. The process of decorating elegant headdresses was done in keeping with the same rules. Coins with holes punched in them were sewn with coarse threads, allowing them to move about. Beads strung on the thread were fastened in dense, horizontal rows, creating a field of color like a background for the main ornamental frieze that run along the circumference of the person’s head.

On older versions, beaded embroidery was the main method used for decoration, and coins played a secondary role, but by the 19th century beaded decoration was of little importance, and was only placed around the edges, ceding to shiny rows of silver. Particular attention was given to how the face was ‘framed’ in a circular manner. Silver coins were hung on the headgear and straps, one above the other, while at the bottom there were large fifty-kopeck and ruble coins. This kind of well-thought-out composition also created a certain harmonious resonance for all the coins. Due to the variety of materials and production techniques, the headpiece appears alive and dynamic. The gentle ringing of silver, and the iridescent movements of light along the beaded rows, impart a special, unique expressiveness to this masterpiece of folk culture.

In ancient times, the hushpu was a headress that was a must for every married woman, and without it she could not go outside. This was reported by Peter Simon Pallas and all the authors in the 18th and 19th centuries that wrote about the Chuvash, calling it a ‘fushpu’, a ‘kashpal’, a ‘hoshpa’, or a ‘hushpu’. They give very contradictory information about this attire, sometimes describing it as a helmet, or a ‘cap’ without a crown, or saying it has the form of a truncated cone.

The hushpu for married women had different shapes, but almost all of them had an open top, as well as a back part in the form of a straight strip of canvas that descended down to waist level. A hushpu that had a helmet-like shape, with a small hole in its upper part, became widespread among the Pribelsk Chuvash. The frame was made from a dense material, and was covered by rows of beads and coins. The conceptual and decorative center of the headdress was a strip of ornamentation with geometric motifs running along the circumference of the person’s head, along the upper edge of the hushpu. The process of decorating elegant headdresses was done in keeping with the same rules. Coins with holes punched in them were sewn with coarse threads, allowing them to move about. Beads strung on the thread were fastened in dense, horizontal rows, creating a field of color like a background for the main ornamental frieze that run along the circumference of the person’s head.

On older versions, beaded embroidery was the main method used for decoration, and coins played a secondary role, but by the 19th century beaded decoration was of little importance, and was only placed around the edges, ceding to shiny rows of silver. Particular attention was given to how the face was ‘framed’ in a circular manner. Silver coins were hung on the headgear and straps, one above the other, while at the bottom there were large fifty-kopeck and ruble coins. This kind of well-thought-out composition also created a certain harmonious resonance for all the coins. Due to the variety of materials and production techniques, the headpiece appears alive and dynamic. The gentle ringing of silver, and the iridescent movements of light along the beaded rows, impart a special, unique expressiveness to this masterpiece of folk culture.