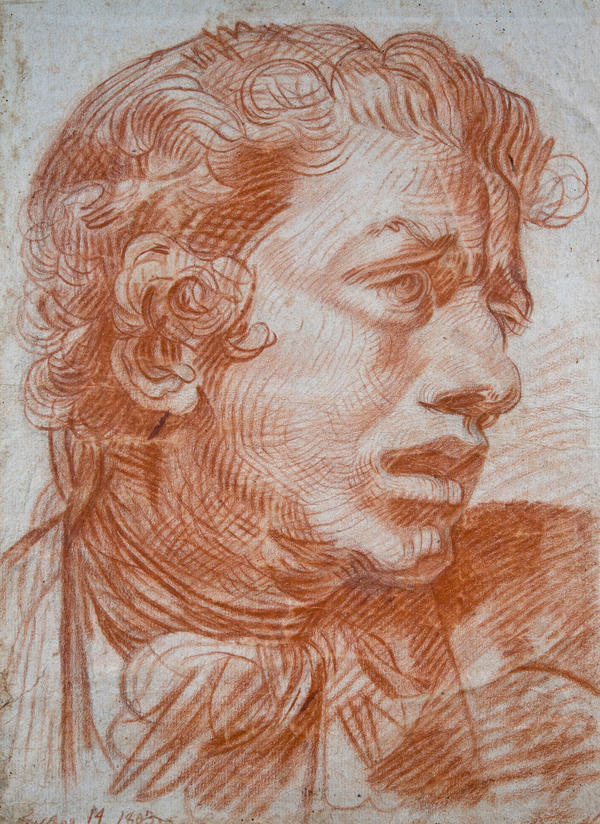

The Head of a Young Man drawing by an unknown artist from the A.V. Stupin School of Painting is a part of the collection of the History and Art Museum of the city of Arzamas. Graduates coming from a serf background did not have the right to sign their works. At the beginning of the 19th century, Pyotr Kornilov, an art historian, wrote that the Stupin School was ‘the only nursery of artistic knowledge for talented serfs.’ For this reason, many works remain unsigned.

All students of the School of Painting were obliged to study drawing. For a whole year, they had two to four hours of drawing every day. The course included a subject titled Drawing All Kinds of Lines, as well as copying originals, drawing gypsum figures and art models.

Since drawing was considered the basis of all arts, pupils of the Stupin School were initiated into the science of drawing during several terms. At first, they had to master basic skills: learn to sit correctly, hold a pencil, and draw lines. Later they began working with the so-called originals — impressions of drawings made by prominent or honor-roll students and by academy teachers.

At the first stage of copying, the students depicted engraved images of parts of the human head and body. Their skills were progressing: after some time, they were able to reproduce proportions and volumes, and to employ different techniques. Head of School and his assistant were supervising the work in the painting studio. This way, Alexander Stupin evaluated talents of each student and developed further education programmes.

In 1809, the Council of the Imperial Academy of Arts started awarding medals to students of the Stupin School, and giving reviews to their best works. Director himself selected them, and Professors of the Academy were ‘pleased by the flair and excellent achievements of the teacher and the students answering. . . its [the Academy’s] expectations for the diligence and talents of new artists receiving education in that area.’ In 1811, the Council members included works by the Arzamas School graduates in the annual retrospective exhibition for the public to view, which meant recognition of their professional achievements.

The final stage of the training was developing drawing skills in a life class. All students who completed the Science of Art programme were acknowledged as skilled sketch artists, and their professional skills were not inferior to those of the Imperial Academy of Arts graduates.

All students of the School of Painting were obliged to study drawing. For a whole year, they had two to four hours of drawing every day. The course included a subject titled Drawing All Kinds of Lines, as well as copying originals, drawing gypsum figures and art models.

Since drawing was considered the basis of all arts, pupils of the Stupin School were initiated into the science of drawing during several terms. At first, they had to master basic skills: learn to sit correctly, hold a pencil, and draw lines. Later they began working with the so-called originals — impressions of drawings made by prominent or honor-roll students and by academy teachers.

At the first stage of copying, the students depicted engraved images of parts of the human head and body. Their skills were progressing: after some time, they were able to reproduce proportions and volumes, and to employ different techniques. Head of School and his assistant were supervising the work in the painting studio. This way, Alexander Stupin evaluated talents of each student and developed further education programmes.

In 1809, the Council of the Imperial Academy of Arts started awarding medals to students of the Stupin School, and giving reviews to their best works. Director himself selected them, and Professors of the Academy were ‘pleased by the flair and excellent achievements of the teacher and the students answering. . . its [the Academy’s] expectations for the diligence and talents of new artists receiving education in that area.’ In 1811, the Council members included works by the Arzamas School graduates in the annual retrospective exhibition for the public to view, which meant recognition of their professional achievements.

The final stage of the training was developing drawing skills in a life class. All students who completed the Science of Art programme were acknowledged as skilled sketch artists, and their professional skills were not inferior to those of the Imperial Academy of Arts graduates.